Up Close with the $400,000 TAG Heuer That Never Was

In existence only for a brief, glorious moment, the Carrera Mikropendulum Tourbillon was TAG Heuer's most complicated and most expensive wristwatch ever, featuring twin tourbillon regulators. This is its tale.

Introduced in 2014, the TAG Heuer Carrera Mikropendulum Tourbillon was an impressive watch, the culmination of the company’s decade long effort to develop exceptional, fraction of a second mechanical chronographs. It was equipped with twin tourbillon regulators: the first a conventional tourbillon for timekeeping, and the other, an innovative magnetic tourbillon regulator for the 1/100th of a second chronograph. But the Mikropendulum Tourbillon never made it into production.’

How it began.. and ended

TAG Heuer unveiled its first exotic chronograph in 2005, a key part of the strategic direction the then CEO Jean-Christophe Babin (who now runs Bulgari). The Carrera Calibre 360 Concept Watch that later evolved into a commercially available limited edition. But it was a modular movement, with an ordinary ETA base movement topped by a custom-made module featuring a second, high-frequency regulator for the 1/100th of the second chronograph.

Led by Guy Semon, a French navy fighter pilot turned engineer, subsequent efforts integrated the twin regulators into one movement, resulting in watches like the Mikrotimer Flying 1000, capable of measuring up to 1/1000th of a second thanks to a balance wheel oscillating at 3.6 million beats per hour (bph). The Carrera Mikropendulum Tourbillon took the concept even further by combining the high frequency regulator with a tourbillon and a balance wheel driven by opposing magnets.

|

| The Carrera Mikropendulum Tourbillon |

But as a result of the drastic pivot in strategy that took place after Jean-Claude Biver took the helm at TAG Heuer in December 2014, the Carrera Mikropendulum Tourbillon was shelved. Biver, the charismatic entrepreneur who made his fortune on reviving Blancpain and Hublot, is aggressively taking TAG Heuer downmarket, focusing entirely on entry-level and mid-range watches (like the new Monaco Calibre 11), leaving no room for pricey, fraction of a second chronographs.

How the Mikropendulum Tourbillon works

The blued central seconds hand blazes around the dial, making one revolution every second. It moves in 1/100th of a second steps, with the chapter ring of the dial graduated for 1/100th of a second. The sub-dial at 12 o’clock records elapsed minutes, while the sub-dial at three is for the seconds. A fan-shaped display at nine is the power reserve indicator.

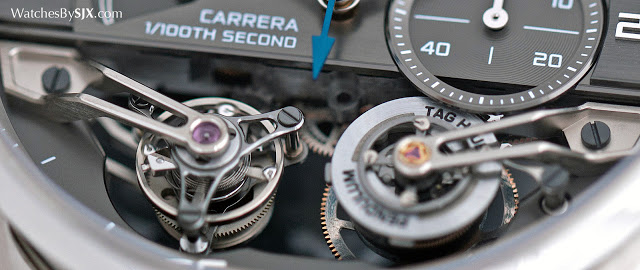

The Mikropendulum Tourbillon is hand-wound, with one mainspring providing power to two gear trains, each connected to one tourbillon. Fully wound it has a 42 hour power reserve.

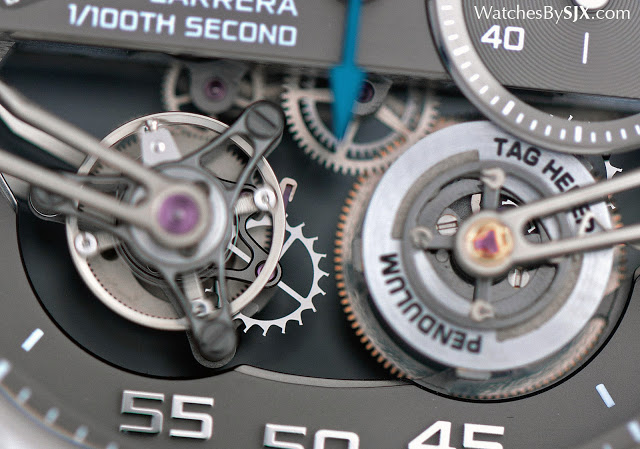

The tourbillon located at seven o’clock is for the timekeeping portion of the movement so it is constantly running. A conventional, one-minute tourbillon, albeit one with a small diameter, it has a silicon hairspring. The small size is necessary in order to maintain a useful power reserve, since a larger balance wheel requires more energy to oscillate.

A magnetic tourbillon regulator

Things get interesting with the other tourbillon regulator at five o’clock. This only starts moving when the chronograph is activated, since it is the regulating organ dedicated to the chronograph. It runs at 50 Hz, or 360,000 bph. That translates into 6000 beats per minute, and 100 per second, which is why the chronograph has a resolution of 1/100th of a second.

The magnetic tourbillon regulator has no hairspring, instead the oscillation of the balance wheel is caused by magnets. Mounted on the balance staff and tourbillon carriage, the opposing forces of the magnets propel the balance wheel back and forth. The advantage of a magnetic balance lies in its stability regardless of temperature or positional changes. Gravity has no effect on its, unlike in a traditional regulator.

However, there is a big downside: at certain angles the magnets perfectly offset each other, freezing the balance. That’s where the tourbillon comes in. By putting it magnetic balance inside a tourbillon that is constantly rotating, there is an external impulse to keep the balance wheel going, eliminating the possibility of it stopping.

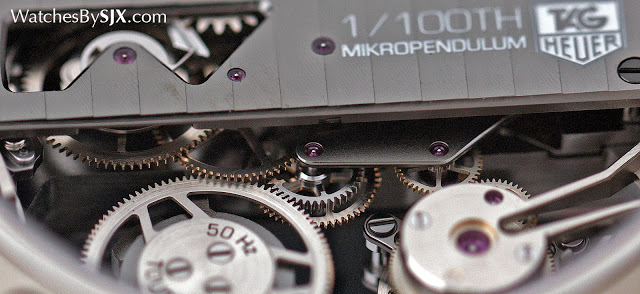

Another challenge was to get the magnetic balance oscillating at its maximum frequency as soon as the chronograph is started. This is done by keeping the balance connected to the gear train and constantly under tension. It is prevented from moving by a brake shaped like a “7”. Once the chronograph is started, the brake pivots away and the balance wheel gets going.

|

| The gears that drive each tourbillon |

|

| The lever that controls the brake is visible at the lower left corner |

Visually the Mikropendulum Tourbillon stuck to the aesthetic found in TAG Heuer’s exotic chronographs, with a 45mm, bullhead-style case and an arched profile.

Priced at SFr400,000, equivalent to US$413,000, the Mikropendulum Tourbillon was initially envisioned as a limited edition of just three pieces. It should have been a mere first step on the way to a 1/1000th of a second chronograph powered by the same magnetic tourbillon. But it was not to be.

Back to top.