Mechanical Wonders at the Louvre, From Ancient Egypt to Vacheron Constantin

Until November 12, 2025.

Having opened on September 17th to coincide with the 270th anniversary of Vacheron Constantin, a philanthropic partner of the museum, Mécaniques d’art is an exhibition at the Louvre dedicated to mechanical art objects, specifically 10 historically significant clocks and watches (though some of the oldest are merely fragments).

On display in the Sully wing until November 12th, the exhibit casts a welcome light on an often-overlooked facet of the museum’s decorative arts collection; objects that blend technical mastery with mankind’s insatiable desire to measure time and understand the heavenly bodies.

The centerpiece (literally, as it’s in the center of the room) is La Quête du Temps, the spectacular astronomical clock unveiled last month by Vacheron Constantin.

For those unable to visit, it’s worth a look at the remarkable objects on display, presented here in historical order.

Exhibition overview

Fragment of a Clepsydra

Egypt, c. 332–30 BC

At approximately 2,300 years old, the oldest clock on display predates mechanical clocks by centuries. Its age explains its condition – a mere fragment is all that remains of an ancient Egyptian clepsydra, or water clock.

As old as this water clock is, the underlying technology was centuries old when it was built. The device was essentially a flat-bottomed vessel with a hole in it, precisely drilled so that water would leak out at a predictable rate; experts estimate that this type of clepsydra could measure time to within about 15 minutes per day, accurate enough for use in practical, ceremonial, or astronomical contexts.

To indicate the time, the inside of the vessel was marked with concentric rings to mark the hours, and even factored in different markings for each of the twelve months of the year to stay in sync with the seasons.

Part from an Automaton Clock in the Shape of a Peacock

Cordoba, c. 962 or 972

The second-oldest clock in the exhibit is also a fragment, which is understood to have formed part of a primitive mechanical clock built for the court of the Caliph in 10th-century Córdoba in Spain.

Due to its similarity to other known Hellenistic clocks of this type, it is believed to have been part of a mechanical peacock that would drop pellets from its mouth to mark the hours.

In courtly contexts, devices like this served the same purpose as crown jewels, and existed to demonstrate the ruler’s power and divine authority. Its artistic form is another reminder that design and decoration have been deeply connected to horology since its early development.

Spherical Watch

Jacques de la Garde, Blois, 1551

The third clock in the exhibit dates to the 16th century when portable spring-driven clocks began to emerge for the first time. The spherical watch on display dates to 1551 and was made in Blois, making it the one of the oldest known French-made watches bearing both a signature and a date.

A primitive device with a single hand, it was no doubt horrendously inaccurate by modern standards, but it represented state-of-the-art technology in its time. A watch like this would have been a marker of social status, in much the same way that haute horlogerie wristwatches are today.

As such, it is painstakingly engraved and decorated, proving that the desire for beauty is as old as time itself.

Table Clock in the Shape of a Square Tower

Germany, late 16th century

As long as clocks and watches have been around, the rich and powerful have sought out or commissioned extraordinary creations to signal their status. The fourth object on display is just such a clock, modelled on a fortified tower and decorated with the coat of arms of the powerful Farnese family of Parma, Italy.

The clock itself is made of brass, bronze, and silver, and was probably made shortly after Jacques de la Garde’s spherical watch. It is richly decorated top-to-bottom to project the owner’s authority and sense of taste. The back of the clock is engraved with an allegory of justice, probably to affirm the righteousness of the Farnese family’s position at the top of society.

The movement is also exposed through glass panels on the side, which reveal a fusée and chain mechanism. While exhibition case backs for wristwatches only date back to the late 1980s, clocks like this show that collectors have been interested in seeing the movement for centuries.

Table Clock with Armillary Sphere

Pierre de Noytolon, Lyon, early 17th century

The oldest complicated mechanical clock in the exhibit was made around the same time as Cardinal Richelieu’s carriage clock, give or take a few years. It’s a small triangular table clock with three dials to indicate the time, the month, the zodiac sign, and the phase of the moon. Above the clock itself is a decorative armillary sphere that represents the major circles of the heavens, including the equator, the tropics, and the polar circles.

Intended as a didactic object as well as a decorative one, the clock reflects the Renaissance fascination with astronomy and its application in the mechanical arts, a through-line that connects contemporary astronomical clocks and watches to those of the past.

Carriage Watch with the Coat of Arms of Cardinal Richelieu

François de Hecq, Orléans, c. 1640

This carriage watch was built to be a traveling companion for Cardinal Richelieu, one of the most powerful political figures of 17th-century France, for whom one of the wings of the Louvre is named. The clock was designed to be suspended from the interior of a coach, and had two functions.

The first was to keep time, though it would not have been especially accurate given the still-primitive state of escapements at the time. It did a better job of its second function, which was to signal the Cardinal’s high status. To this end, the case is lavishly engraved and features the owner’s coat of arms.

Watch in the Shape of a Skull (Memento Mori)

Jean Rousseau, Geneva, mid-17th century

The first Swiss watch in the exhibit dates to the mid-1600s, and features a striking skull motif that was popular at the time. This kind of object is known as a memento mori, and is intended to remind the owner of death and the fleeting nature of time, something that continues to be a niche theme in contemporary watchmaking.

This example opens at the jaw to reveal the dial. The outer surface is engraved with biblical scenes and quotations from Saint Paul. The movement inside is conventional for the period; it would not have been a great timekeeper but it would have been an effective reminder of mortality.

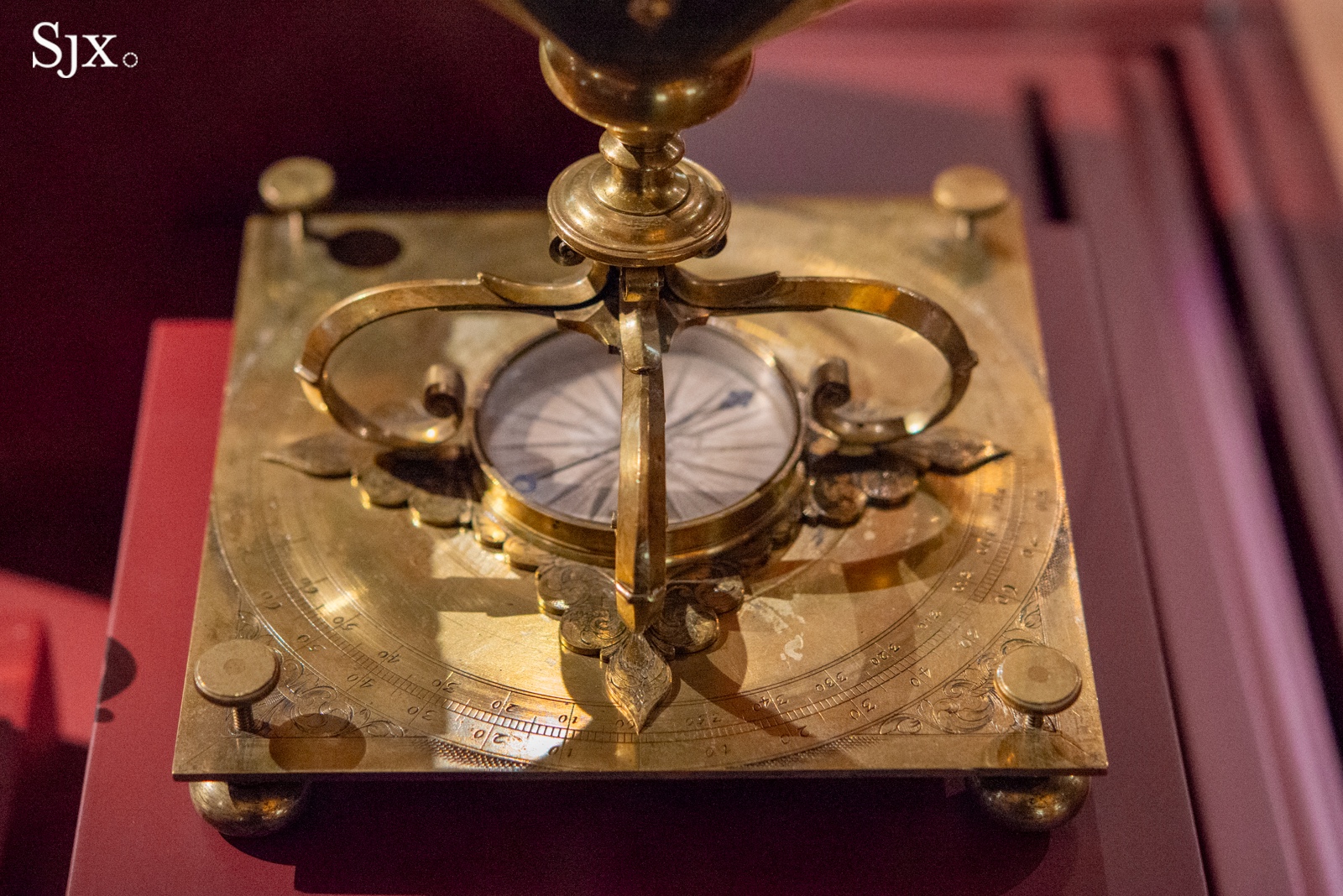

Polyhedral Dial

Pierre Sévin, Paris, 1662

Once the property of the “Grande Mademoiselle” Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, this sundial features four dials with a compass in its base. Made long before the introduction of time zones, it would have displayed the same time on all four dials when oriented correctly.

Not strictly a clock, the polyhedral dial represents the convergence of science, design, and aristocratic taste. Its presence in a royal collection underlines the value placed on scientific knowledge during the reign of Louis XIV.

Pendulum Clock of the Creation of the World

Claude-Siméon Passemant & the Lepaute brothers, Paris, 1754

One of a number of extraordinary astronomical clocks built by Passemant, the ‘Creation of the World’ was commissioned for Louis XV. This elaborate astronomical clock integrates a rotating globe, a spherical moon phase indicator, and an orrery showing planetary motion.

Part scientific instrument, part political statement, royal clocks like reinforced the ideal of rational order and the monarch’s place within it. Vacheron Constantin funded the restoration of this clock in 2017.

La Quête Du Temps ‘Mecanique D’art’

Vacheron Constantin, Geneva, 2025

Covered in-depth during its official unveiling for the brand’s 270th anniversary, La Quête du Temps is a monumental astronomical clock and automaton built by Vacheron Constantin in collaboration with François Junod and L’Epée 1839.

Standing over a metre tall and weighing 150 kg, La Quête Du Temps features a three-part structure topped by a humanoid automaton known simply as Astronomer, a gold-plated figure encased in a dome painted with the Geneva sky as it appeared on the date of the company’s founding in 1755.

The clock combines retrograde hours, a perpetual calendar, a 15-day power reserve, moon phase, tourbillon, and sidereal time. Astronomer animates on demand, using 158 cams to perform 144 distinct movements across three sequences, each accompanied by music.

Appropriate given the complexity of the clock, Vacheron Constantin is staffing the exhibit with specialists to explain its functions and its position in the broader context of the exhibition.

Conclusion

As a visitor to this exhibit, I could not help being struck seeing a contemporary object like La Quête Du Temps given pride of place, encircled by some of the most significant clocks and watches in the Louvre’s collection. By exhibiting a work of modern haute horlogerie alongside objects spanning over two millennia, the exhibit affirms watchmaking as a living art; its history is still being written.

The objects on display also prove that fine expressive decoration is not a recent fad, but has been a part of watchmaking since before the invention of the verge escapement.

Mécaniques d’art

Musée du Louvre – Sully wing, room 602

Open daily (except Tuesdays) through November 12, 2025

Plan a visit on Louvre.fr.

Back to top.