Long-Hidden Patek Philippe Watches Headline Sotheby’s NY Sale

Graves, Packard and... Emery?

This December at its New York auction. Sotheby’s will bring one a hitherto secret collection of complicated Patek Philippe watches to market, The Olmsted Complications Collection.

Accrued by late financier Robert M. Olmsted over six decades, the collection includes watches commissioned by the most prominent American collectors of the early 20th century, including Henry Graves Jr., Thomas E. Emery, James M. Morehead III, and Elliot C. Lee, some of which were completely unknown to the public until now.

An “Extra” quality observatory watch made for Henry Graves Jr.

It couldn’t be better timed either, with the flagship lot being a previously undocumented Patek Philippe perpetual calendar desk clock, just months after the brand launched its modern equivalent.

Better still – at least for American bidders – these watches are already stateside, avoiding the hefty import taxes levied against Switzerland. In addition to rare and exotic pocket watches, the auction also makes room for a few watches with more mainstream appeal, including a Rolex ref. 6100 with a cloisonné enamel dragon dial.

The Thomas E. Emery Desk Clock

The headline lot is a Patek Philippe desk clock made for one Thomas Emery – the same client who commissioned Patek Philippe’s first wrist-borne perpetual calendar in 1925. Until now there were only two publicly known Patek Philippe perpetual calendar desk clocks, those made for James Ward Packard and Henry Graves Jr.

Like its siblings, Emery’s desk clock has a silver wedge shaped cabinet. Inside is a large key-wound and key-set movement with a perpetual calendar and an ten-day power reserve from two barrels.

The movement in Emery’s clock is, practically speaking, the same as that found in the Graves, giving it a much different dial from Packard’s, which inspired Patek Philippe’s modern desk clock, launched earlier this year. The movement in Emery’s clock, however, has one refinement the others lack: a diamond end stone for the balance, which Patek Philippe used sparingly.

The clock’s original owner was Thomas E. Emery, whose family owned Emery Industries, a Cincinnati-based chemical company. Emery passed in 1975, and according to Sotheby’s, Olmsted acquired the clock in 1976, making him only the second owner.

Interestingly, Daryn Schnipper of Sotheby’s revealed that Patek Philippe claimed not to know of the timepiece’s existence, despite it being recorded in their books. That implies the firm’s records aren’t fully digitised, or at least haven’t been thoroughly analysed, meaning the Patek Philippe Museum’s information advantage over private collectors may be less significant than previously thought – at least for now.

The Emery deck clock carries an estimate of US$500,000 to $1 million.

Two watches with four movements for James M. Morehead

Another of Patek Philippe’s important American clients, John Motley Morehead III, had a penchant for unusual watches. He commissioned a triple complication with a double, split chronograph – as in two separate chronographs and split seconds, not two rattrapantes. Morehead also commissioned a pair of unusual and beautiful double-movement watches, which come to market for the first time.

Both are minute repeaters, and one has a chronograph with split seconds and a minutes totaliser. Patek Philippe presumably sourced both movements (for both watches) from Victorin Piguet, a complications-focused établisseur in the Vallée de Joux that had a very close relationship with Genevan watchmakers. The firm is best known for coordinating construction of the Henry Graves Supercomplication for Patek Philippe.

Turning the crown clockwise winds the primary (complicated) movement, while turning the crown counterclockwise winds the simple movement underneath – like most two-train watches of this era. You can set the primary movement by pulling out the crown (negative setting) while the secondary movement sets with the aid of a small pin at one o’clock. The secondary movements aren’t easily accessible in either watch, but the rates can be easily adjusted using a lever by the escape wheel bridge on one watch, and an adjustment screw on the other.

Movements of the watch without chronograph.

While I’ve seen a handful of pocket watches that are essentially two movements that share a main plate, and I even know of one with a balance on the dial side and another on the back, I don’t know of any others with two discrete movements stacked on top of each other.

Movements of the watch with chronograph.

The obvious explanation for this arrangement is that one movement tracks civil time, and the other, sidereal time. Morehead had such a passion for the celestial that he donated the Morehead Planetarium to his alma mater, the University of North Carolina. However, purpose-built sidereal timekeepers usually use a 24-hour time scale, so perhaps it was for another reason entirely.

The less complicated of the two is expected to hammer for between US$300,000 and $500,000, while the chronograph model is valued between US$500,000 and $1 million.

The most conventional of Morehead’s watches is a minute repeating clock watch with grand et petite sonnerie, made in 1906 by Patek Philippe. Morehead passed in 1965, the same year Olmsted acquired the three watches, once again making him their second owner.

The sonnerie is estimated at a comparatively modest US$100,000 to $200,000.

Elliot C. Lee’s Grand Complicated Tourbillon

The most complicated watch from Olmstead collection revealed so far is a Dent grand complication made for another prominent American collector, Elliot Cabot Lee, in 1901. It is a minute repeating clock watch with grande et petite sonnerie, perpetual calendar, and split seconds chronograph with 60-minute totaliser.

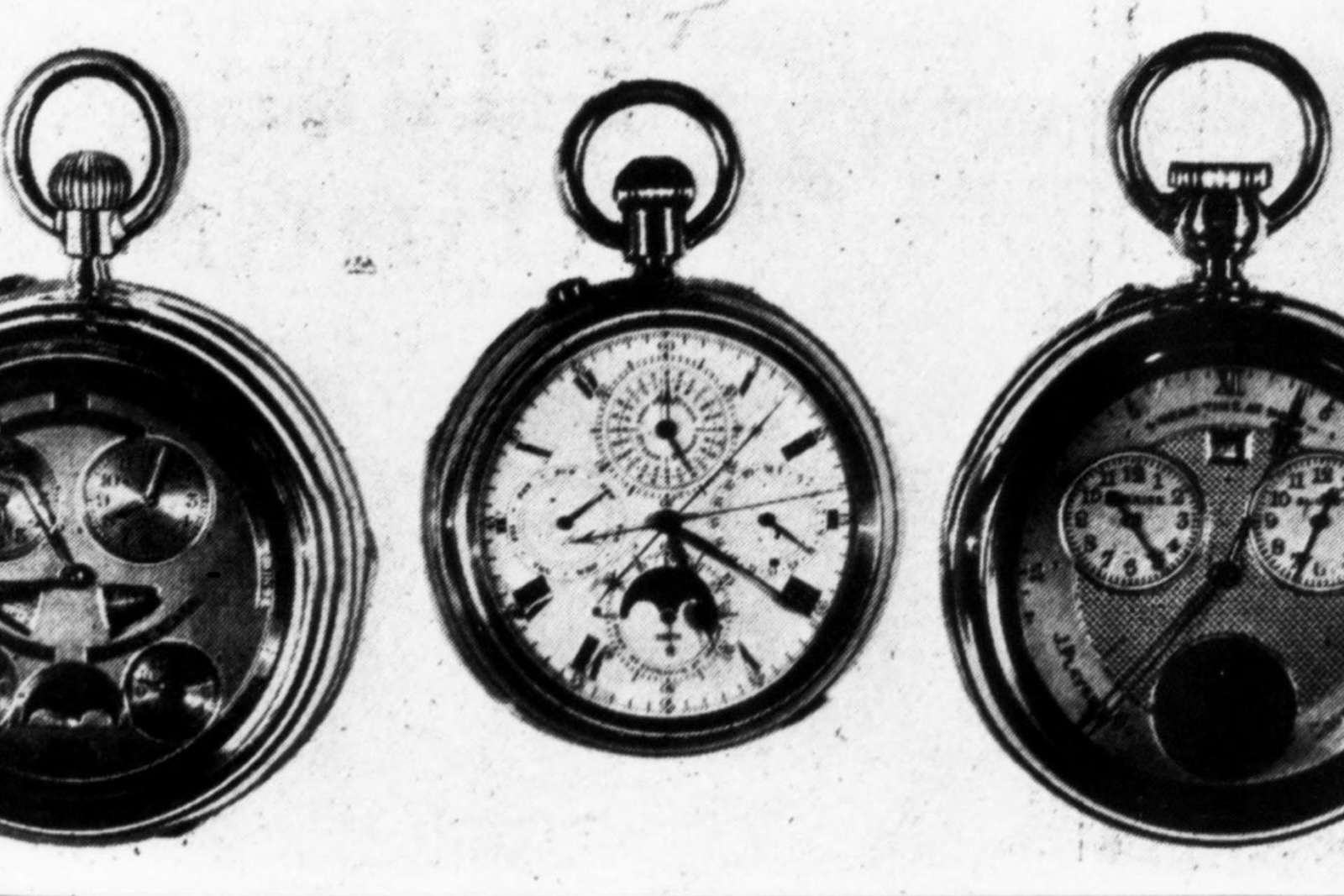

The watch photographed with other members of the Lee Collection. Image – The Jewelers Circular and Horological Review 1924

Louis-Elisée Piguet’s firm in Le Brassus supplied the ebauche, while the massive tourbillon is the work of Nicole Nielsen. It features a semi-helical or “duo-in-uno” hairspring, which is half flat and half helical, matched to an English lever escapement.

The Dent grand complication carries an estimate of US$150,000 to $250,000.

A Familiar Frodsham

No, you are not experiencing déjà vu, this watch is in fact the near identical twin of no. 09649, with which we went hands-on with last year. It is just as massive, with an elaborate engine-turned dial.

Tourbillons are common today, but were much rarer and highly revered in 1915 when this watch was built, with only a highly skilled few specialising in their construction and adjustment. One would assume the tourbillon subassembly was entirely of English make, like the Dent, but on close inspection, this English tourbillion uses a Swiss-style club-tooth steel escape wheel – make of that what you will.

Oddly, the watch only has grand sonnerie striking. More affordable repeating clock watches often omitted the more complicated petite sonnerie function, suppressing hour strikes except on the new hour.

However, this watch would have been the furthest thing from “affordable”. When it was made, it would be been extraordinarily expensive, partially because English watches were far more expensive than Swiss watches in general, but mostly because of the tourbillon.

The Frodsham’s historical value translates to an estimate of US$300,000 to $500,000.

For more about Important Watches featuring Exceptional Discoveries: The Olmsted Complications Collection, visit sothebys.com.

Back to top.