Insight: The Evolution of Patek Philippe Marketing Since 1839

Defining haute horlogerie for almost 200 years.

Often behind every watch brand’s marketing and image is an overarching influence that can be subtle or explicit. For Patek Philippe, that influence reveals a long arc of intention, carried across centuries, shaped by consistency, and reinforced through a remarkable alignment between product and message.

From its early days in royal courts to modern-day exhibitions in New York and Shanghai, the company has approached communication as a reflection of its philosophy. Over nearly two centuries, Patek Philippe has maintained a consistent approach to communication – measured, stable, and aligned with the brand’s long-term perspective.

The manner of Patek Philippe telling its own story is perhaps as interesting as its watches. We trace the way in which Patek Philippe has communicated over time, from introducing itself to the mind of the client, to adapting to a changing world, all while remaining aligned with its values. We also examine the brand’s choices in language and imagery, looking in particular to its early references to inheritance, which evolved into the familiar campaign that continued across decades.

Launched in 2025, but perhaps enjoyed by many generations to come

Foundations and Royal Recognition (1839–1877)

When Patek Philippe was founded in 1839, the idea of advertising a luxury watch was almost nonexistent. Most manufacturers relied on trade reputation, medals at international exhibitions, and word-of-mouth among wealthy clientele. In contrast to today, almost all watches were sold by third-party retailers and distributors who were primarily responsible for marketing, leaving watchmakers to just make watches.

The 19th century’s dominant marketing platforms were world’s fairs, retailers’ printed catalogues, and window displays in prestigious stores. Public advertising was largely limited to basic listings in trade directories or society newspapers. Mass communication held little relevance for a product often made for heads of state and captains of industry.

While more established firms like Vacheron Constantin and Breguet drew on deeper histories and longstanding networks, Patek Philippe, then still a newcomer, advanced through deliberate participation in exhibitions, careful retail placement, and the symbolic power of its keyless winding mechanism. It built an early reputation through institutional exposure and personal association.

The brand’s posture was defined by selectivity. The company appeared in settings that conveyed legitimacy: international fairs, respected retailers, and commissions that carried public weight. Communication was structured through deed rather than display, for instance a patent filing, a jury medal, a royal presentation. In this framework, the brand’s identity took shape through action and context, expressed in its creations, presentation, and reception by tastemakers who shaped standards of excellence.

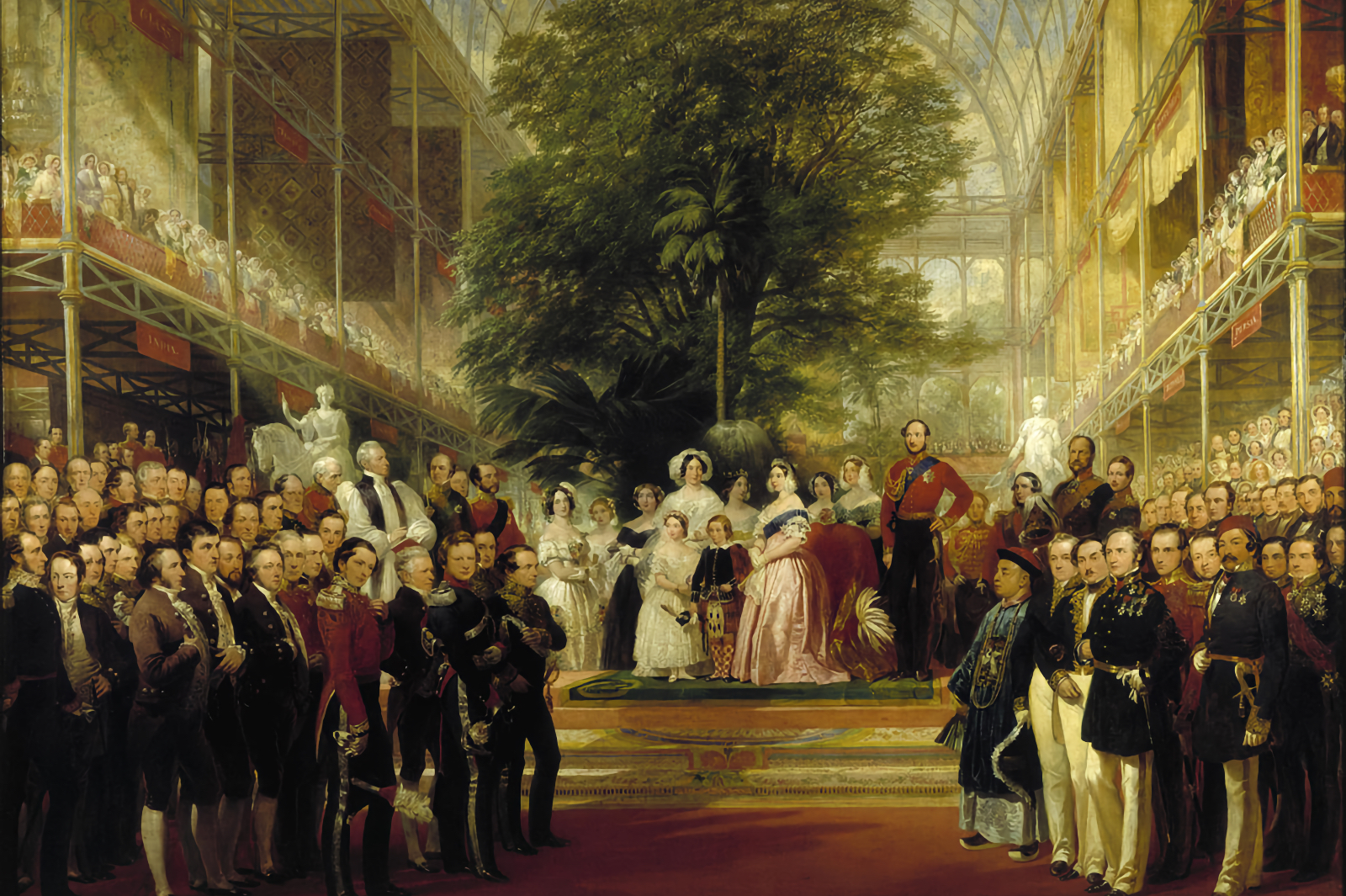

Opening of the Great Exhibition in London by Queen Victoria on May 1st 1851. Image – Wikipedia

The company’s royal breakthrough came in 1851 at the Great Exhibition in London, where Queen Victoria was gifted a blue enamel pendant watch that is today in the Patek Philippe Museum.

This highly visible endorsement, paired with a gold medal awarded at the fair, immediately linked the firm to royalty. But Patek Philippe’s reputation was also built on technical distinction.

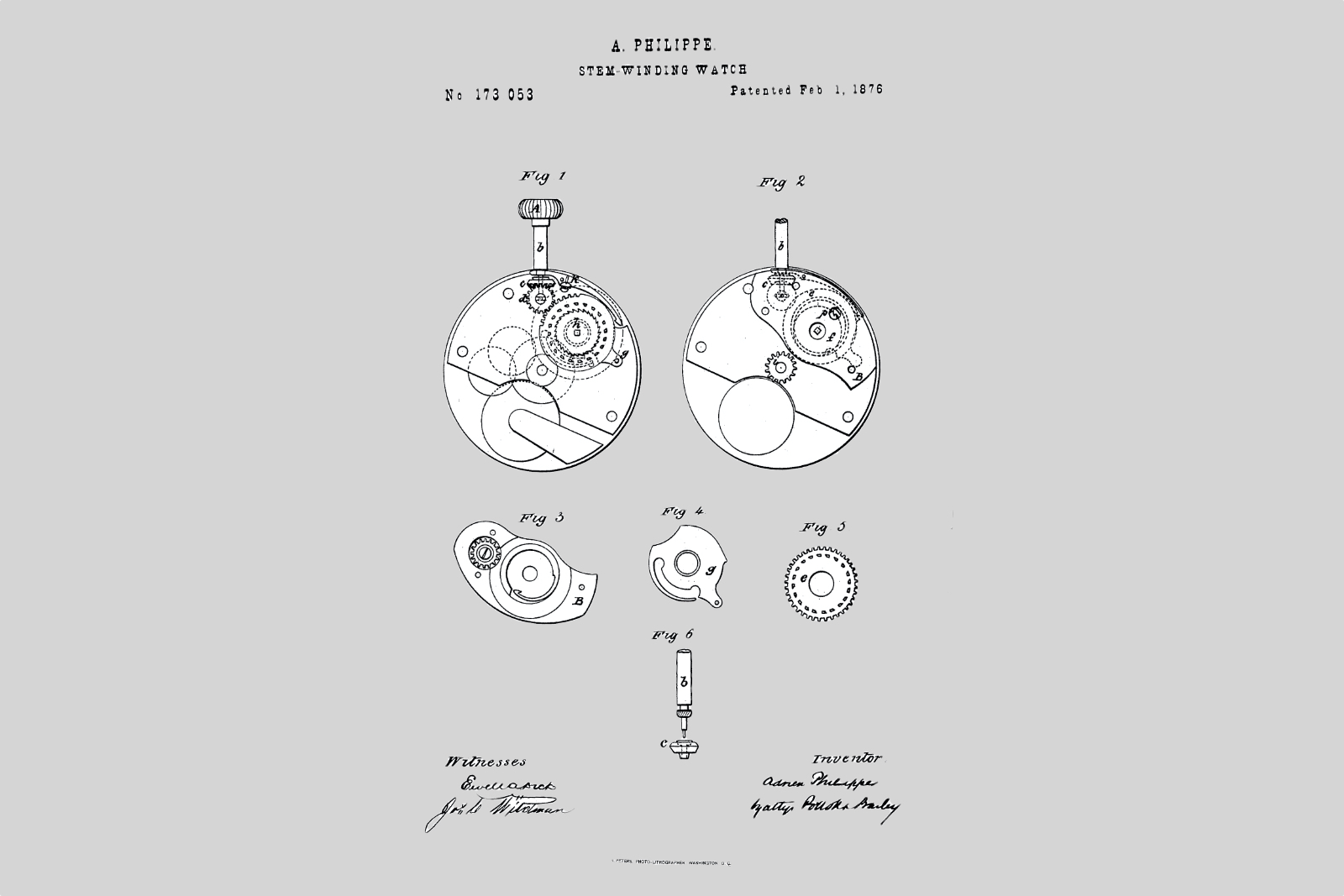

One of its key innovations was Jean Adrien Philippe’s 1844 invention of the keyless winding and setting mechanism, an elegant solution that allowed the user to wind and set the time through the pendant. It eliminated the need for a separate key and set a new standard for simplicity and refinement in horology. As noted in Patek Philippe: The Authorized Biography, this technical contribution was one of the defining factors in the firm’s early acclaim.

Philippe’s American patent filed in 1876 for his keyless winding system invented in 1845

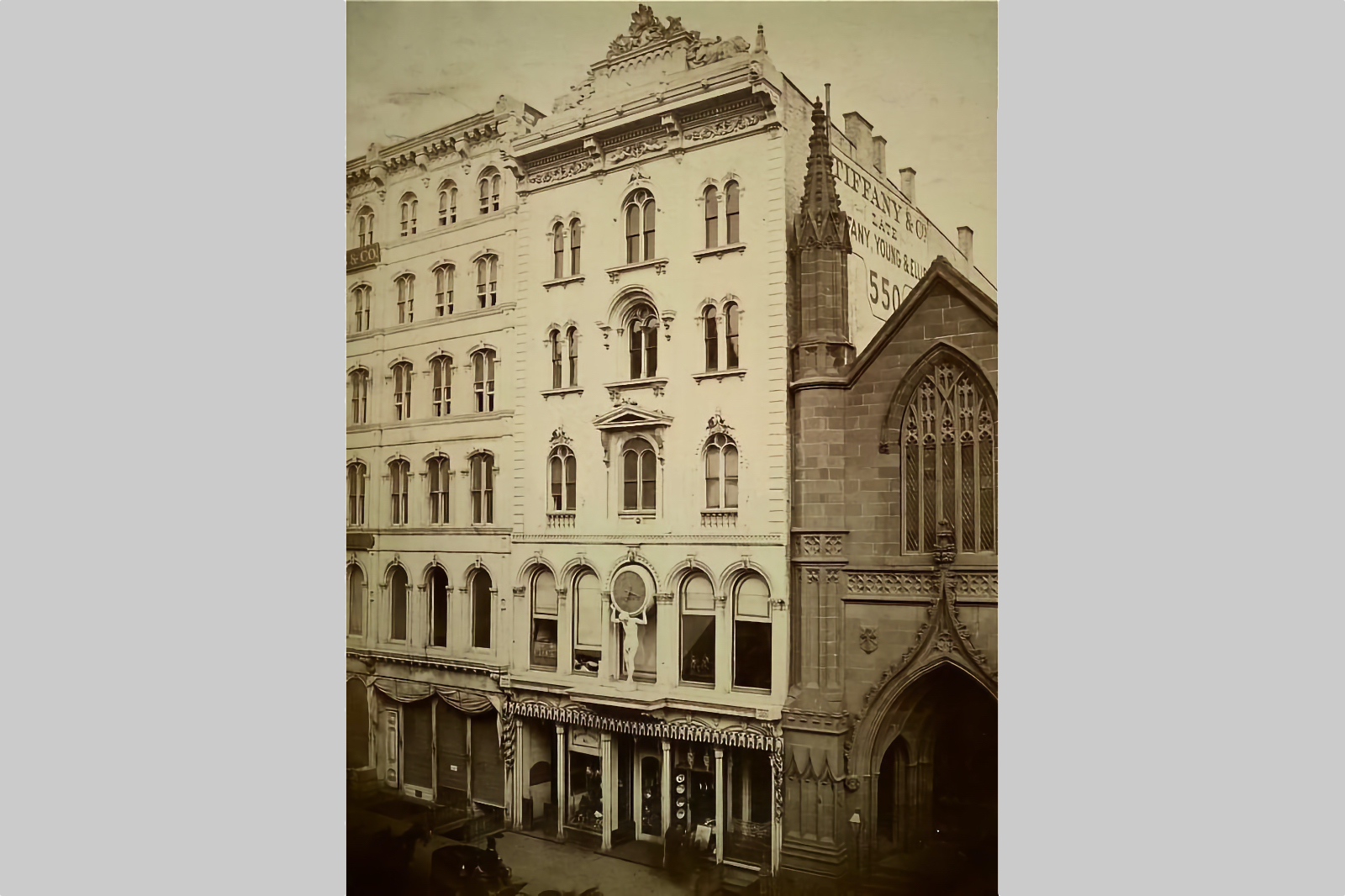

In the same year that Queen Victoria acquired her watch, Patek Philippe also began a formal retail partnership with Tiffany & Co. in New York. This marked an early recognition of the American market’s potential and reflected a clear strategy of working through trusted intermediaries.

Tiffany’s, already associated with refinement and a discerning clientele, became an important representative of the brand’s identity in the United States. According to John Reardon’s Patek Philippe in America, this partnership laid the foundation for the brand’s long-standing success in the United States, decades before the establishment of Patek Philippe’s own subsidiary in the United States, the Henri Stern Watch Agency (HSWA).

Through this partnership, Patek Philippe entered the American market with cultural and commercial credibility. This early relationship helped shape the way the brand would be perceived in the United States – a European marque attuned to American standards of taste and trust.

Tiffany & Co. at 15 Union Square West in New York City in the 1870s. Image – Curbed/flickr

By the late 19th- and early-20th century – by then the brand counted amongst its clients Queen Louise of Denmark, Pope Pius IX, and Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria – Patek Philippe’s image had been shaped by mechanical innovation, refined design, and association with influential patrons. Reputation developed through presence, earned by timely inventions, high-profile endorsements, and strategic alignment with the values of cultural and technical excellence.

Retail Presence and Early Advertising (1878–1902)

By the final quarter of the 19th century, the landscape of marketing was shifting. Industrialisation had introduced new consumer categories, and advertising was beginning to find its form through illustrated posters, branded packaging, and paid placements in newspapers and journals. In Paris, London, and New York, luxury goods were increasingly promoted through high-end department stores, theatrical catalogues, and ornate retail displays designed to attract the growing bourgeois clientele. Branding was becoming visual, and advertising more assertive.

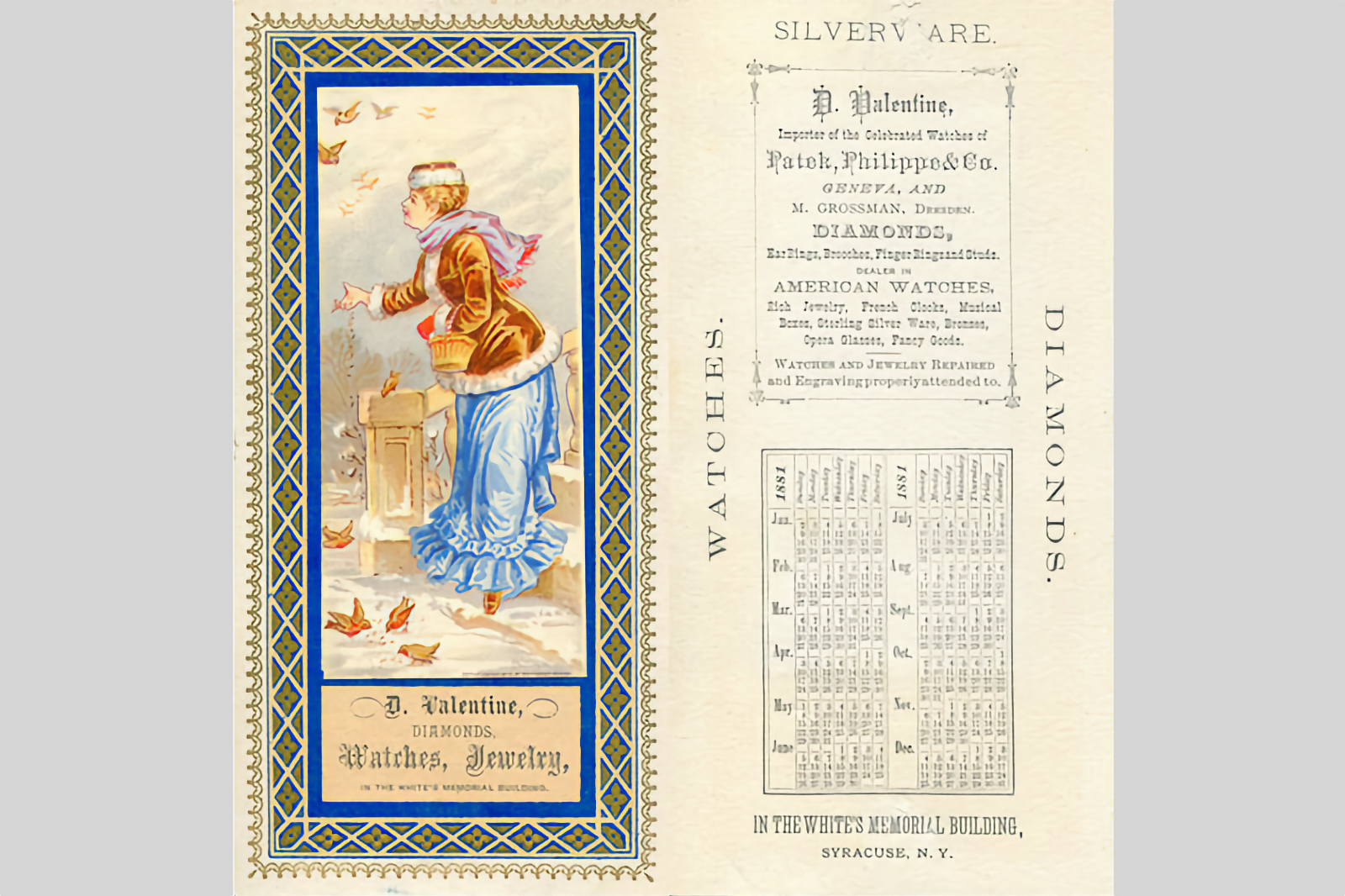

An 1881 calendar card from American Patek Philippe retailer D. Valentine in Syracuse, New York. Image – Collectability

Patek Philippe, however, maintained a position at the edges of this change. Its watches appeared in public-facing formats, but always filtered through a layer of curatorship, either through the jewellers who carried them or through participation in horological exhibitions. According to Patek Philippe: The Authorized Biography, the firm’s retail presence during this period followed a strict policy of select representation, offering visibility without mass availability. Retail operated more like a gallery system: select dealers in major cities showcased the brand in controlled environments, and promotion came through the reputation of the seller.

The brand’s name began appearing in trade publications and society listings, often alongside descriptions of medals or royal patrons. These early advertisements were rarely self-authored; more often they were short notices placed by retailers or distributors, sometimes accompanied by stock line engravings or general claims about precision and elegance. These printed mentions conveyed prestige without overt persuasion, and reflected the brand’s preference for mediated presentation.

1901 advertisement by French retailer Paul Maux mentioning Patek Philippe in La Vie Montpelliéraine. Image – Gallica

What distinguished Patek Philippe in this period was its insistence on selectivity. Where other watchmakers expanded rapidly through larger dealer networks and broader product lines, Patek Philippe limited its exposure. Distribution was kept narrow. Clients were addressed indirectly, through the prestige of the store or the printed mention in a reputable journal. No slogans, no testimonials, no pricing tables, just presence, reputation, and the quiet authority of craftsmanship.

At the turn of the century, as illustrated advertising began to saturate the urban press, Patek Philippe stood apart by continuing to rely on positioning. Its name might appear in a jeweller’s window or on the title page of a catalogue, but the watch remained the subject of attention instead of the object of promotion.

Heirloom Messaging and United States Agency Formation (1903–1948)

In the early decades of the 20th century, advertising grew increasingly sophisticated. The rise of consumer culture brought with it the language of aspiration, sentiment, and identity. Brands across industries began to craft messages that appealed to emotion rather than function. In print media, especially in the United States, advertisements spoke in full paragraphs, paired with ornate illustrations or bold type, and began to tell stories around the product. Luxury, once assumed, now required narrative.

Atlanta jeweller Maier & Berkele’s 1903 advertisement. Image – Collectability

Patek Philippe moved through this shift at its own pace. The firm remained measured in tone and limited in exposure, though signs of adaptation began to emerge, particularly in the American market. In 1903, American jeweller Maier & Berkele ran an advertisement describing Patek Philippe as “worth passing from father to son.”

According to Patek Philippe in America, this marked one of the earliest known expressions of the heirloom concept in the brand’s American messaging. It was a short sentence, but a decisive one. It introduced the concept of generational ownership, framed in terms of continuity and long-term significance. This phrasing quietly set the tone for what followed.

Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, Patek Philippe’s advertising presence remained modest. Dealer ads appeared occasionally in major city newspapers, typically within jeweller listings or in seasonal gift guides. The language often emphasised precision and Swiss heritage. Imagery was limited, and the text carried more weight than visuals. In tone, these ads aligned with the formality of the period, subdued, direct, and positioned toward individuals who valued tradition.

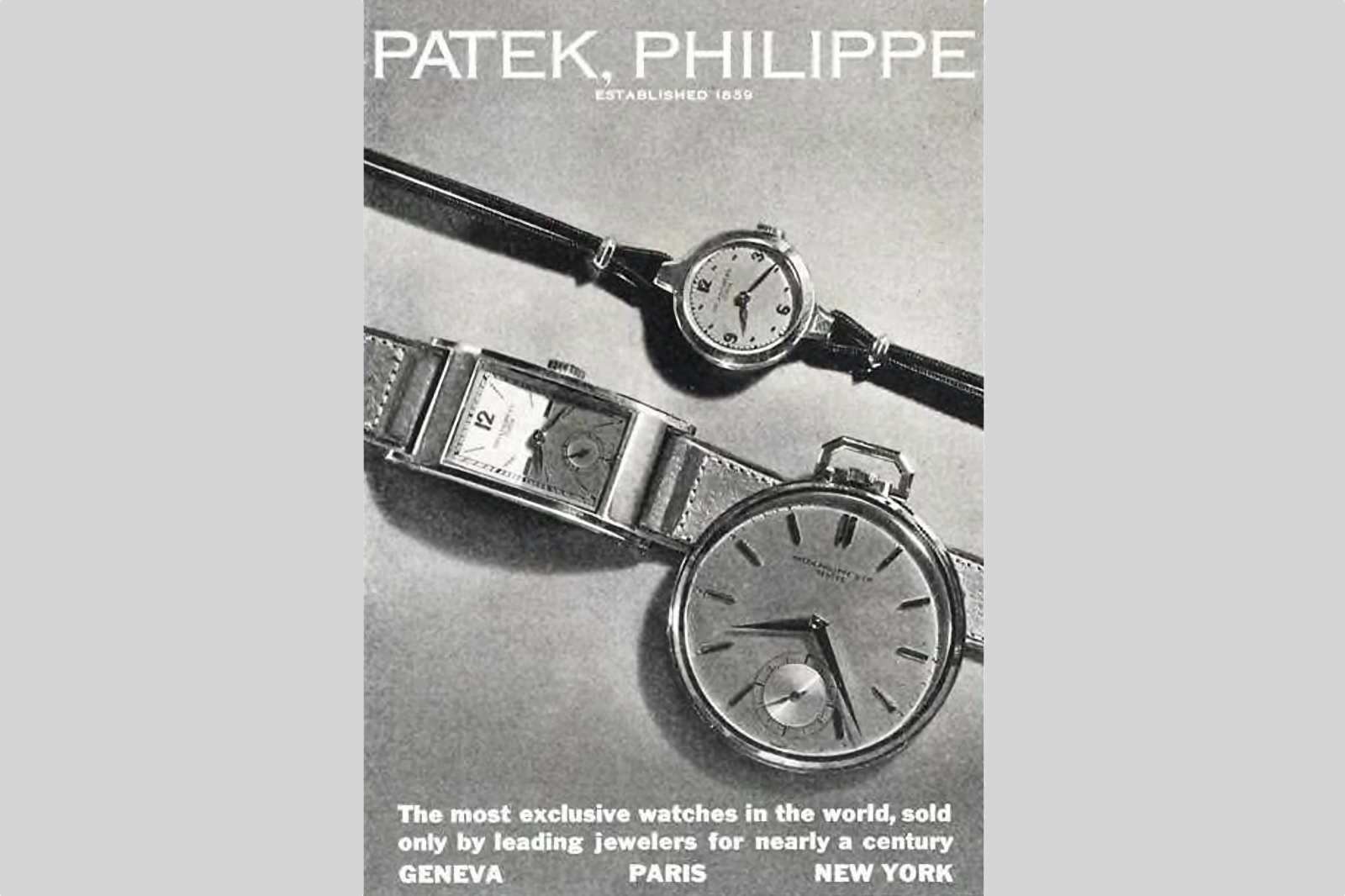

Patek Philippe ad published by the HSWA in 1937. Image – Private Archive

A turning point came in 1932, when the Stern family acquired Patek Philippe. Family ownership, established during a period of global economic strain, reinforced the company’s long-term outlook and shaped its strategic posture for the decades ahead.

In the United States, this led to the creation of HSWA in 1942, a dedicated distributor that would define the brand’s presence in the American market. Named after Charles Stern’s son Henri, who had been sent to the United States to oversee the crucial market, HSWA served as both a logistics base and a communications hub, responsible for translating the brand’s identity into the language of American print culture.

Patek Philippe ad, published by the HSWA in 1942. Image – Private Archive

By the late 1940s, HSWA began to shape a more intentional narrative for Patek Philippe in the United States. In 1945, a newspaper ad described the watch as one “to be treasured from generation to generation.” Four years later, in 1949, a similar campaign featured the line: “Your great-grandson may wear this watch.” These messages framed the product as a personal legacy, placing emphasis on continuity and inheritance over status. They marked the beginning of a campaign language built around permanence and time understood in familial terms.

Many luxury brands of the period turned to celebrity endorsement and visual glamour. Patek Philippe followed a different path, focusing its voice on longevity, stewardship, and personal significance. This direction, quietly introduced through HSWA’s ads, set the foundation for what would become the brand’s most enduring campaign. Its roots were already visible in the understated language of inheritance.

The American Moment Begins (1949–1969)

Postwar America became the world’s most influential consumer market, and with that came a rapid transformation in advertising. The 1950s and 1960s saw the rise of full-page newspaper placements, television commercials, celebrity testimonials, and the golden age of Madison Avenue ad agencies. Brands across industries leaned into mass communication, and aspirational marketing became central to luxury goods, from automobiles to fashion to watches.

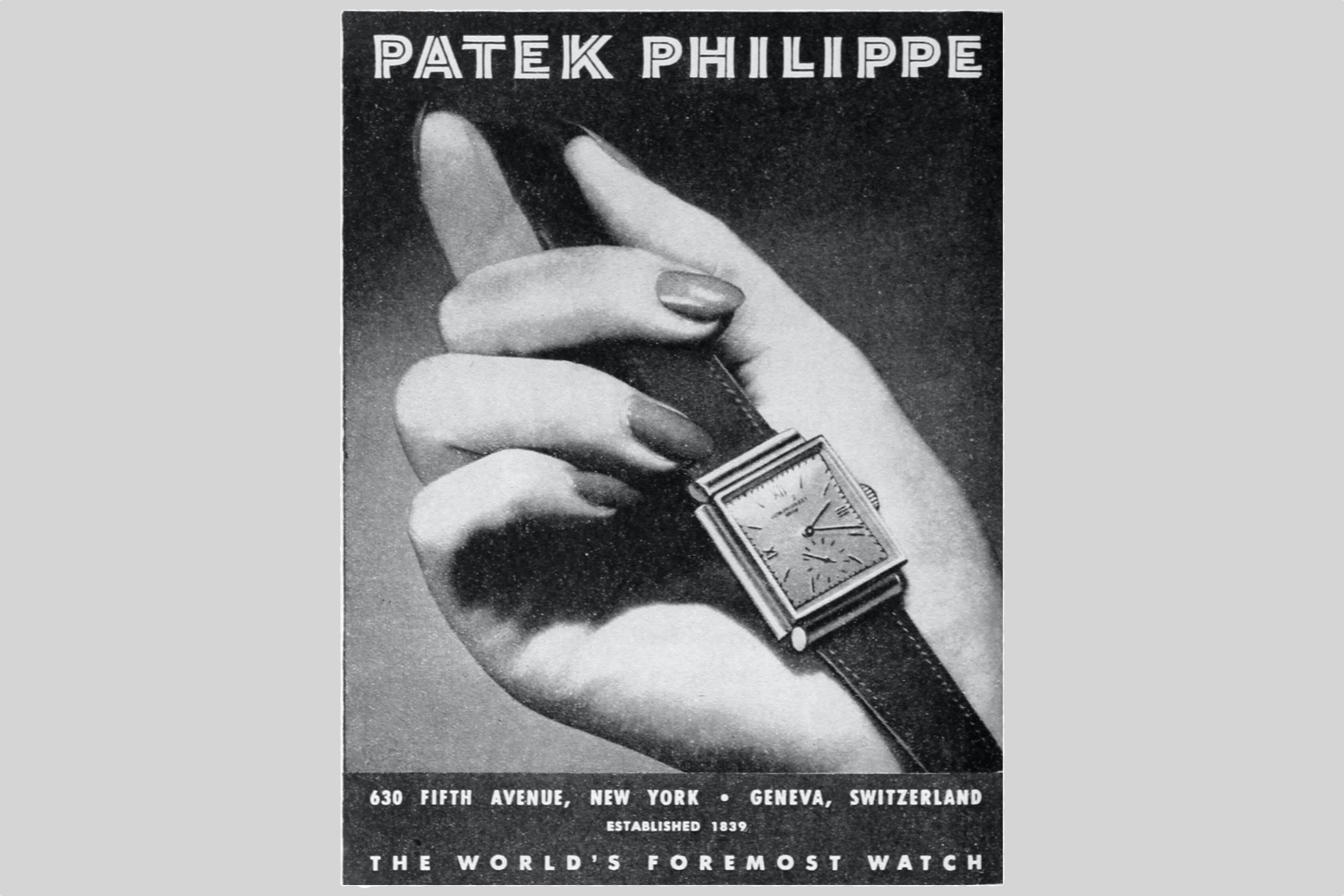

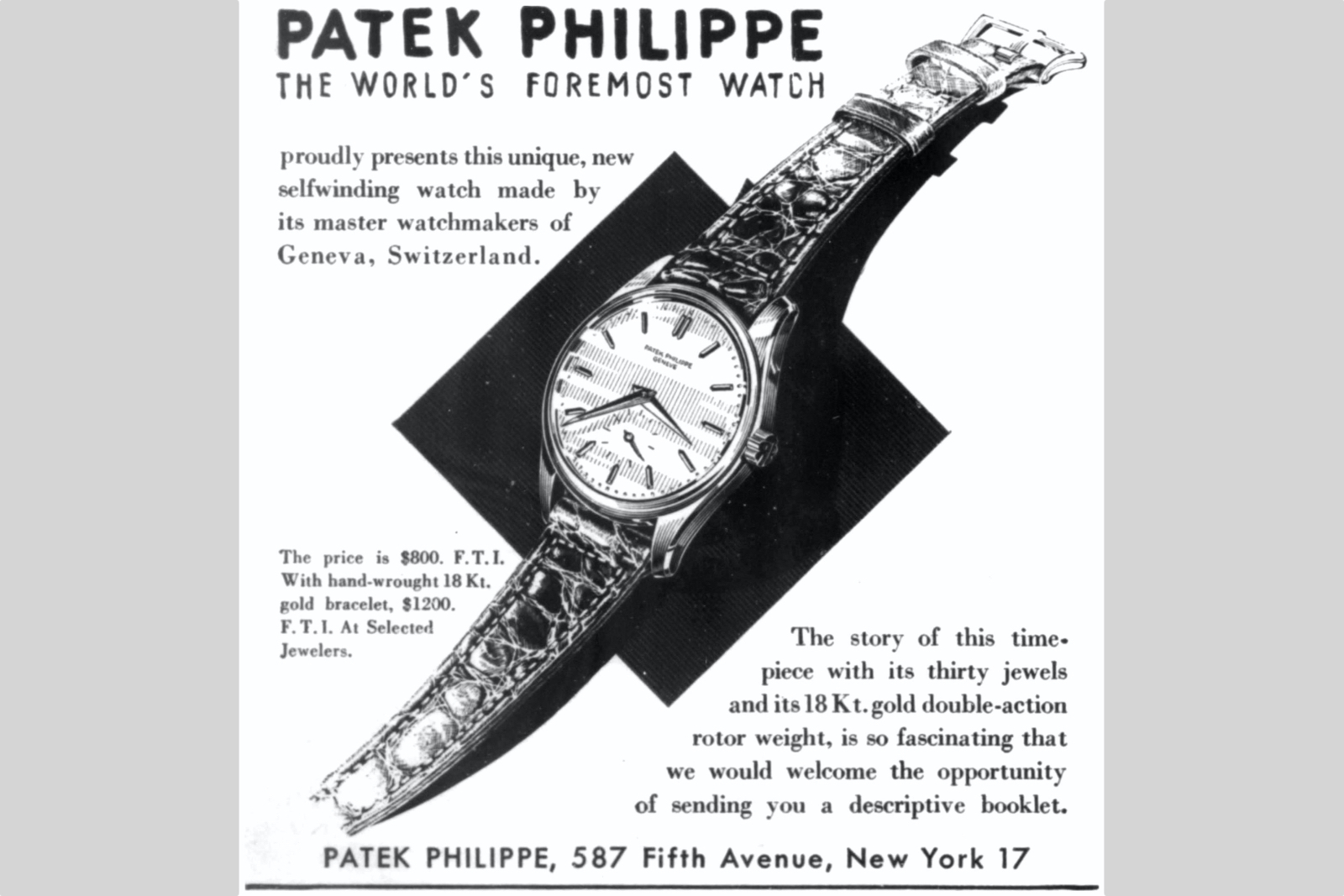

Patek Philippe ad, published by the HSWA in 1955. Image – Private Archive

For Patek Philippe, this era marked the beginning of a structured presence in the United States, largely directed through HSWA. According to Patek Philippe in America, HSWA operated with a high degree of autonomy, shaping brand perception through selective advertising, retail programming, and strategic restraint. Rather than adopting the tone or scale of mainstream luxury advertising, the agency developed its own approach, one that preserved the reserve of the brand while finding resonance with the American consumer.

During these two decades, Patek Philippe advertising in the United States took on a slightly more narrative voice. Ads placed by the HSWA in publications such as The New Yorker, Town & Country, and The New York Times maintained formal, concise language. The themes continued to center around permanence, craftsmanship, and intergenerational value. Watches were presented as symbols, carrying meanings of achievement, responsibility, and continuity.

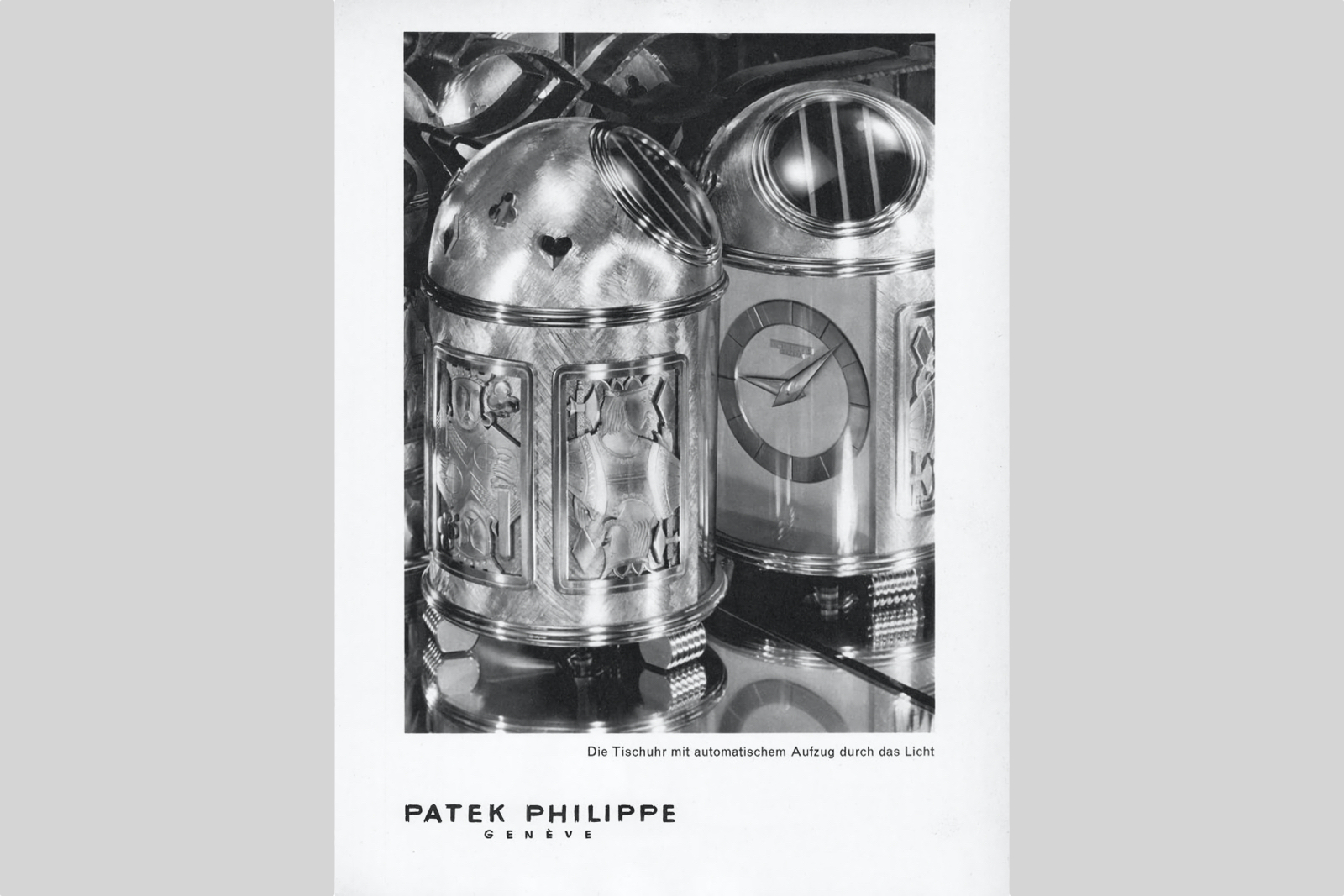

Patek Philippe German ad, published in 1957. Image – Private Archive

Print designs from this period were restrained: black-and-white layouts, serif typography, and minimal imagery. A single reference, often shown in profile, might appear beside a short paragraph that referenced Geneva, tradition, or longevity. Product copy was surrounded by white space, creating a sense of calm and clarity uncommon in the era’s increasingly crowded ad pages.

Although mass-market brands were turning to celebrities and product glamour, Patek Philippe emphasised anonymity and discretion. No faces were used. No slogans repeated across pages. If there was emotion, it was quiet, a gesture toward pride in one’s legacy, or the dignity of owning something that would outlast its first wearer. According to Patek Philippe: The Authorized Biography, this approach reflected the company’s broader resistance to trend-based visibility in favour of long-term meaning.

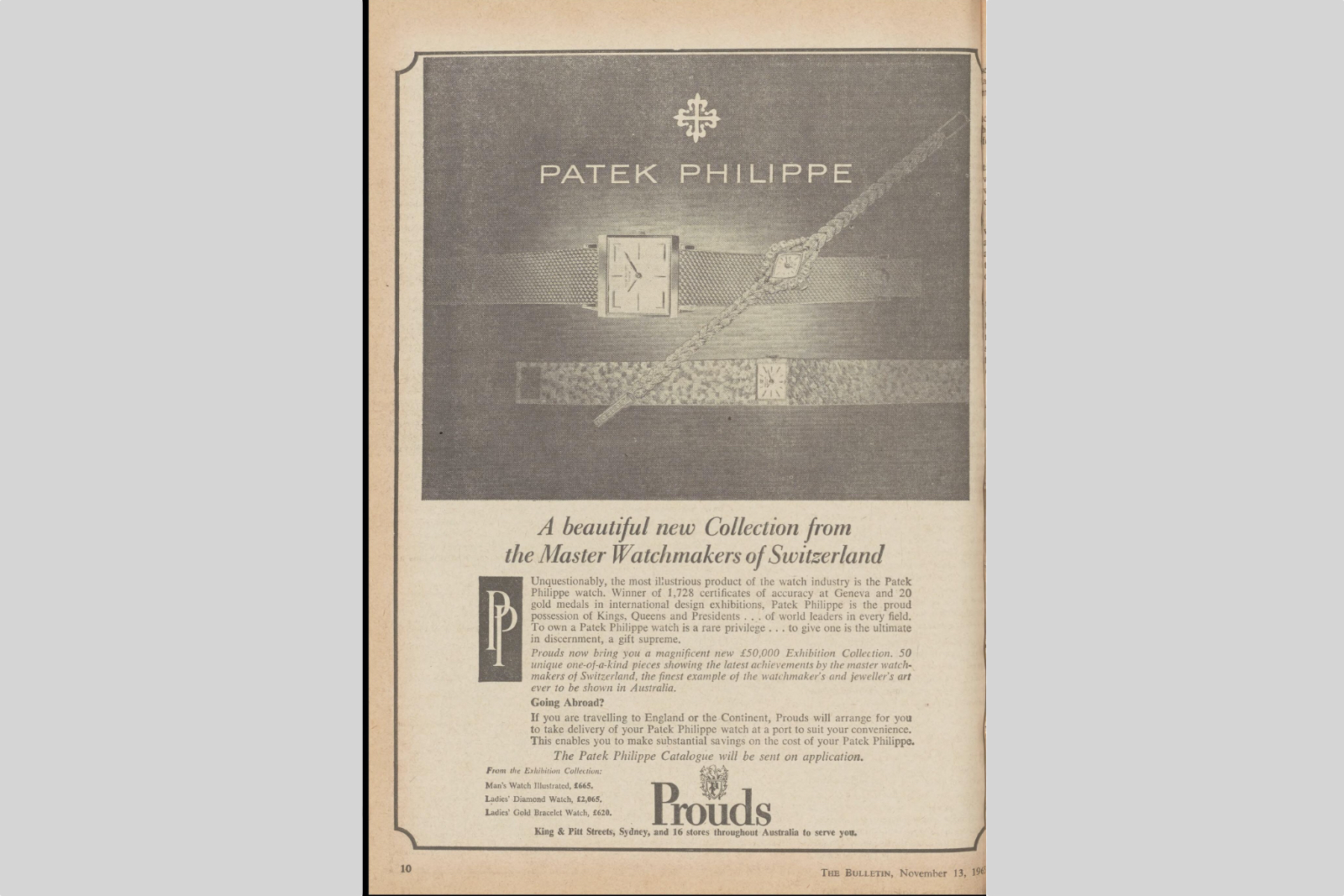

Patek Philippe Australian ad, published in 1965. Image – Private Archive

This period also saw the brand’s first steps into exhibition-based marketing in the United States. In-store events at authorised retailers, sometimes accompanied by displays of rare timepieces or historical documentation, gave clients a curated experience. These events functioned as soft-spoken brand theatres: part education, part aspiration, and entirely in tune with the company’s communication values.

The American strategy in these years helped prepare the ground for future campaigns. It introduced narrative restraint in a market known for spectacle, and it framed the Patek Philippe watch as a personal object, drawing attention through presence and quiet focus over overt appeal.

Creative Identity and Exhibition Strategy (1970–1985)

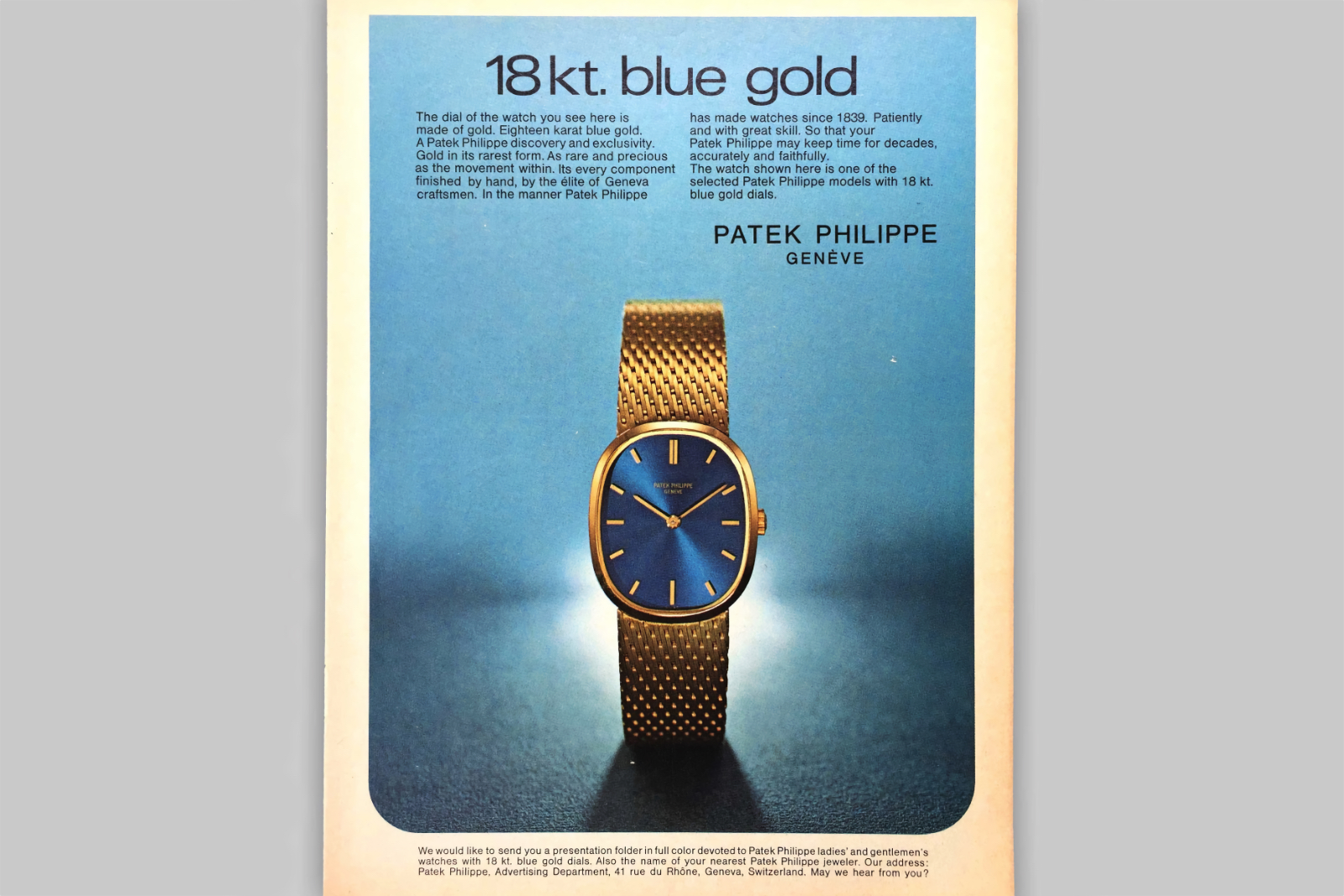

As the luxury market expanded in the 1970s, advertising entered a new phase defined by bold imagery, lifestyle branding, and increasing emphasis on visual association. Magazines became vehicles for symbolic identity, glossy pages filled with models, exotic settings, and logos treated as cultural signals.

In the watch industry, this translated into campaigns built around celebrity wearers, sport affiliations, and glamour photography. Brands such as Omega and Cartier leaned into personality-driven promotion, while quartz disruption pushed others toward more urgent messaging.

Patek Philippe 1974 to 1978 ad campaign. Image – Private Archive.

Patek Philippe moved through this period on its own terms, refining a language of understatement. Its visual identity in advertising remained minimal, clean lines, plain backgrounds, and isolated images of the watches themselves. Headlines were succinct, copy was measured, and the tone remained aligned with values already established: discretion, permanence, and generational appeal. This period demonstrated the brand’s commitment to continuity in the face of increasing visual noise.

A defining moment of this period came in 1976 with the introduction of the Nautilus. Patek Philippe launched the watch with a paradox: “One of the world’s costliest watches is made of steel.” Showing the watch against a simple background, without wrist or wearer, the advertisement disrupted expectations. In a market where steel typically signified utility or affordability, the line challenged assumptions and asserted value through confidence and restraint.

According to Patek Philippe: The Authorized Biography, this campaign was conceived to break through the visual clutter of the period without abandoning the brand’s voice. The message was quiet and deliberate: value could be redefined without the need for ornament or explanation.

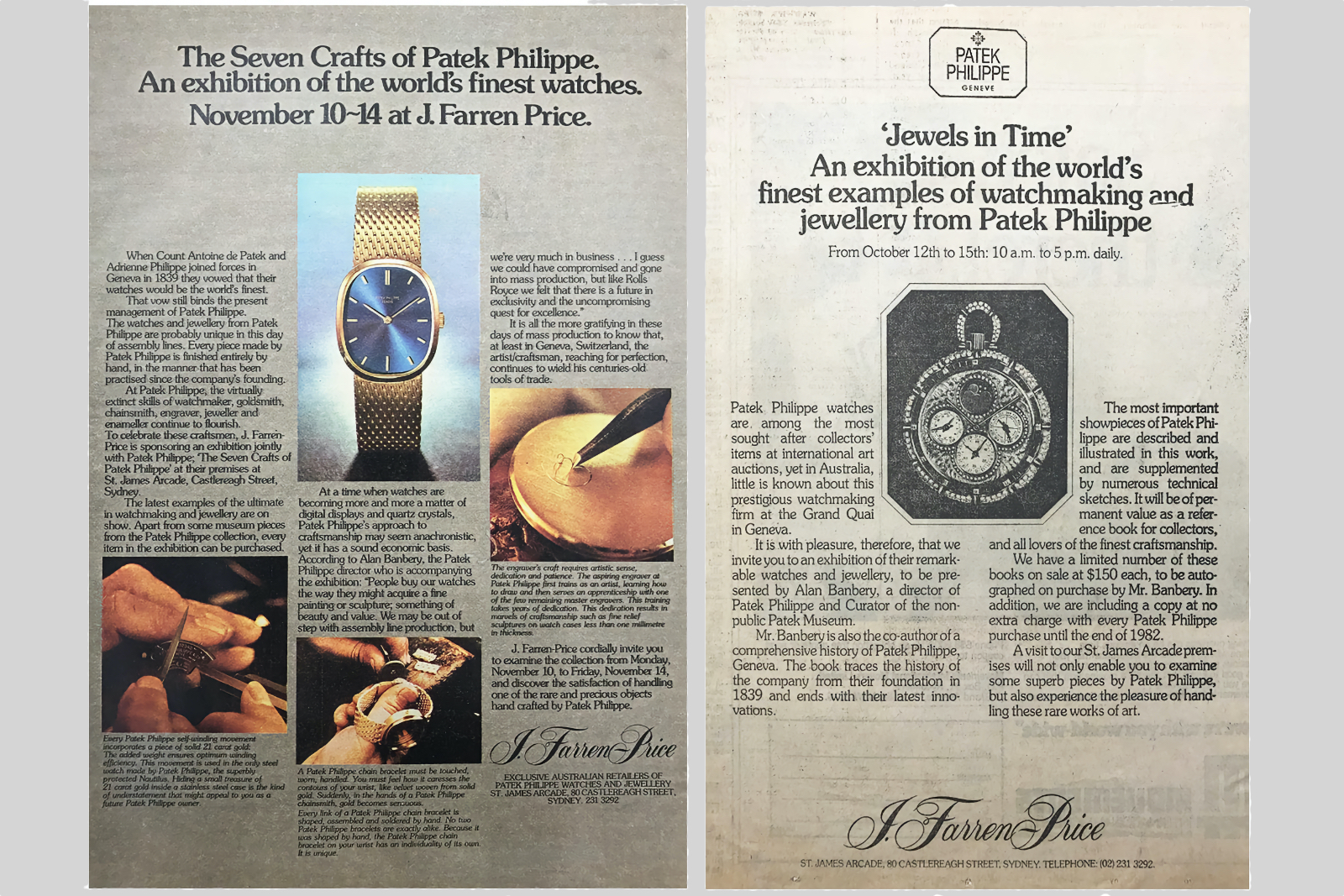

1980s ads by Australian retailer J. Farren Price announcing in-house exhibitions. Image – Private Archive

Alongside this shift in product language, Patek Philippe began experimenting more deliberately with exhibitions. The United States market, where HSWA continued to serve as strategic lead, became a testing ground for experiential engagement. These exhibitions went beyond sales; they were curated presentations of history, mechanics, and craft. As documented in Patek Philippe in America, they offered clients and journalists a deeper view into what the brand considered essential: lineage, innovation, and restraint.

These exhibitions stood apart from typical trade show appearances. Patek Philippe focused on intimate displays, often presented in collaboration with museums or prestigious retailers. Archival materials, vintage watches, and craft demonstrations were used to tell a story of continuity, of a company moving forward while keeping its past fully present.

The overall marketing stance during this period resisted the dominant trends. While others embraced movement, speed, and celebrity, Patek Philippe deepened its commitment to controlled visibility. Even in the release of a sports watch, the campaign maintained composure. And in each exhibition, the brand reaffirmed that its message, like its watches, was built to endure.

The Bittel Era and Global Messaging (1986–1995)

By the mid-1980s, luxury advertising had settled into its mature phase. Brands sought consistency across markets, cultivating global identities anchored in logo, typography, and tone. Prestige was visualised through lifestyle photography, yachts, private jets, Alpine chalets, and advertising emphasised access to a particular world, often through association with celebrities or aspirational imagery. In the watch industry, many leading names relied on large-format magazine ads, recurring ambassadors, and high-volume exposure across both fashion and business press.

The Calatrava Ref. 3919 inaugurated Patek Philippe’s first global ad campaign in 1987 . Image – Private Archive

Under René Bittel, who led Patek Philippe’s international marketing through much of the 1980s and early 1990s, the brand sharpened its visual and linguistic discipline. Bittel’s role was pivotal in translating the company’s foundational reserve into a consistent global posture. The tone remained discreet, but the message became more unified.

This was the period when the Calatrava ref. 3919 emerged as a symbol of the brand’s identity. Slim, classically proportioned, and paired with a white dial and hobnail bezel, it was chosen as the face of the first truly international Patek Philippe advertising campaign.

The accompanying ad was simple and its layout was spare: the watch placed against a white background, with a small block of copy. No actors, no props, no dramatisation. The tone conveyed confidence without affectation. In contrast to the heavily styled ads of the period, Patek’s imagery felt quiet and self-assured. As noted in Patek Philippe: The Authorized Biography, this campaign marked the first unified global articulation of the brand’s values through advertising.

This campaign marked the first time Patek Philippe presented a single voice across continents. American, European, and Asian markets received the same creative direction, reinforcing a global identity grounded in refinement and clarity. In parallel, the brand avoided endorsements, product placement, and personality-driven exposure. Value was expressed through coherence: the consistency of message, design, and form.

At the same time, the exhibition strategy launched in the United States decades earlier continued to mature. Patek Philippe began presenting archival materials, movement architecture, and rare timepieces in traveling formats. According to Patek Philippe in America, these exhibitions helped create a more intimate form of brand communication, where historical perspective gave depth to the present collection.

These exhibitions remained modest in scale, with a clear purpose: to create emotional proximity between collector and brand through depth of context. By presenting what came before, the company gave meaning to what was being produced in the present.

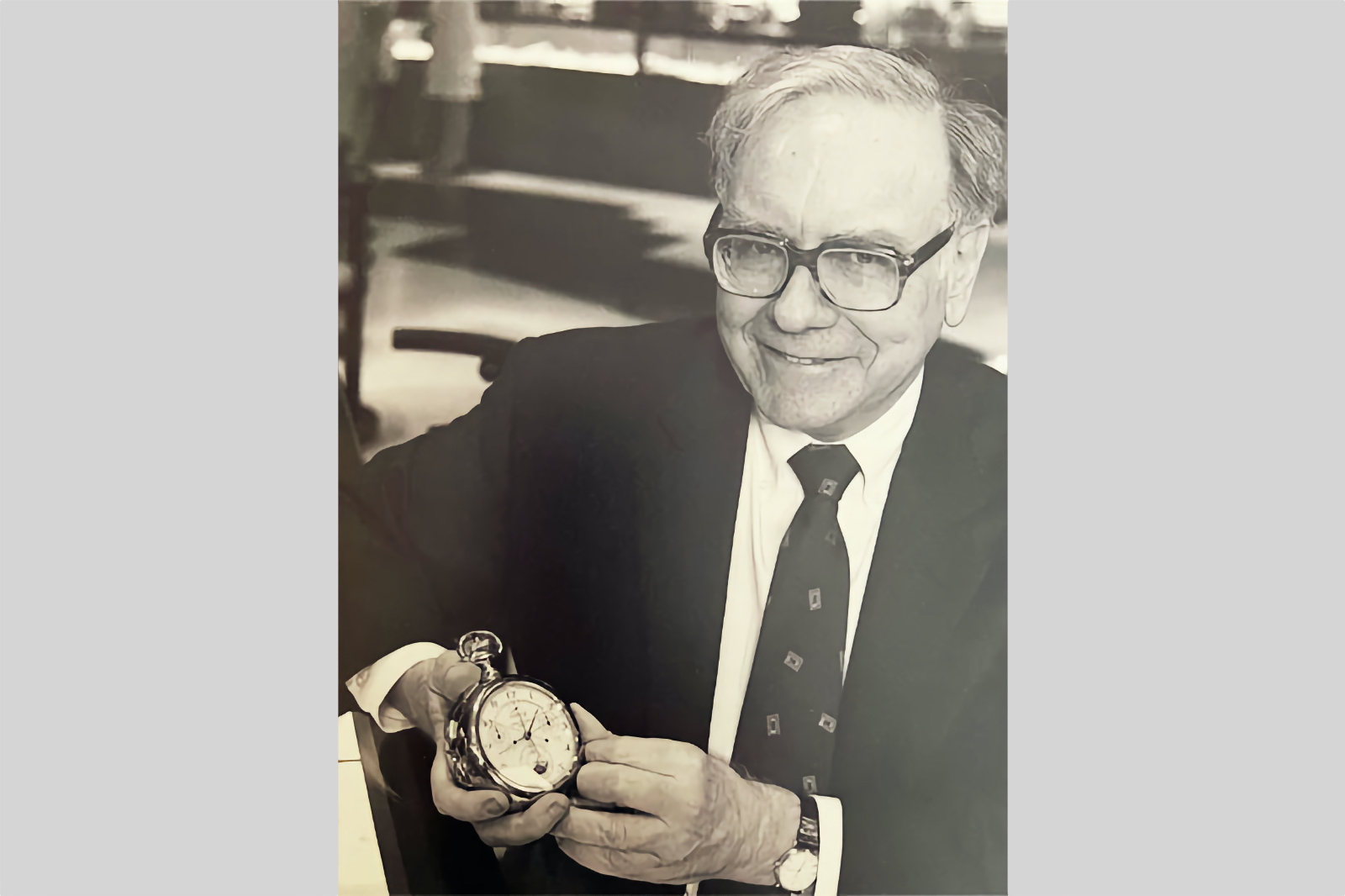

Warren Buffet holding the Caliber 89 during a private exhibition in 1995 . Image – Collectability

In 1995, a brief moment of unplanned publicity captured this alignment between brand philosophy and external perception. Warren Buffett, one of the world’s most prominent value investors, was photographed holding the white gold Calibre 89.

The caption read: “The six billion dollar man holds the six million dollar watch.” Though not part of any campaign, the image circulated widely. It reinforced the idea that ownership of a Patek Philippe represented a long-term view: one of value, of permanence, of time itself.

As the decade drew to a close, Patek Philippe stood apart in a field increasingly shaped by short-term messaging and visual noise. Its communication approach relied on restraint, editorial clarity, and a consistent alignment between product design and the words used to describe it. The foundation was in place for something more lasting.

The Generations Campaign and Emotional Language (1996–2005)

In the mid-1990s, the luxury watch industry was dominated by image-led campaigns built around celebrities, bold product photography, and status symbolism. Many brands framed ownership as personal reward or visual assertion. The language of advertising leaned heavily on ambition and lifestyle, especially in the American and Asian markets. Emotional storytelling, when used, was often secondary to product display.

Patek Philippe chose a different route. In 1996, following a strategic review led by Jasmina Steele, the brand’s longtime communications director, the brand parted ways with its longtime advertising partner and began searching for a new agency. The selection of London-based Leagas Delaney marked a decisive shift. The brief was clear: avoid spectacle, preserve meaning, and establish an identity that reflected values already embedded in the product itself. What followed was a complete rethinking of how a watch brand could speak.

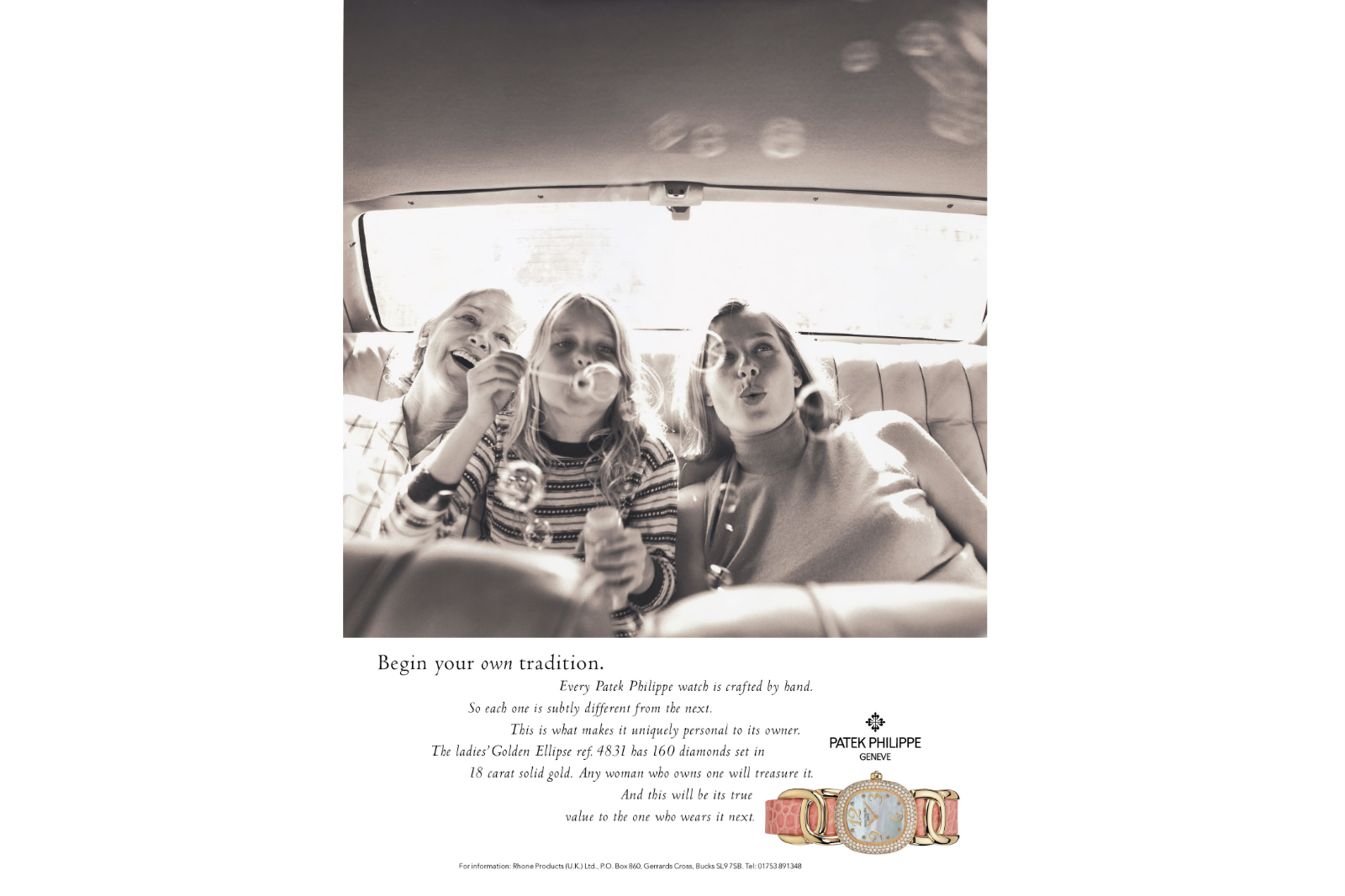

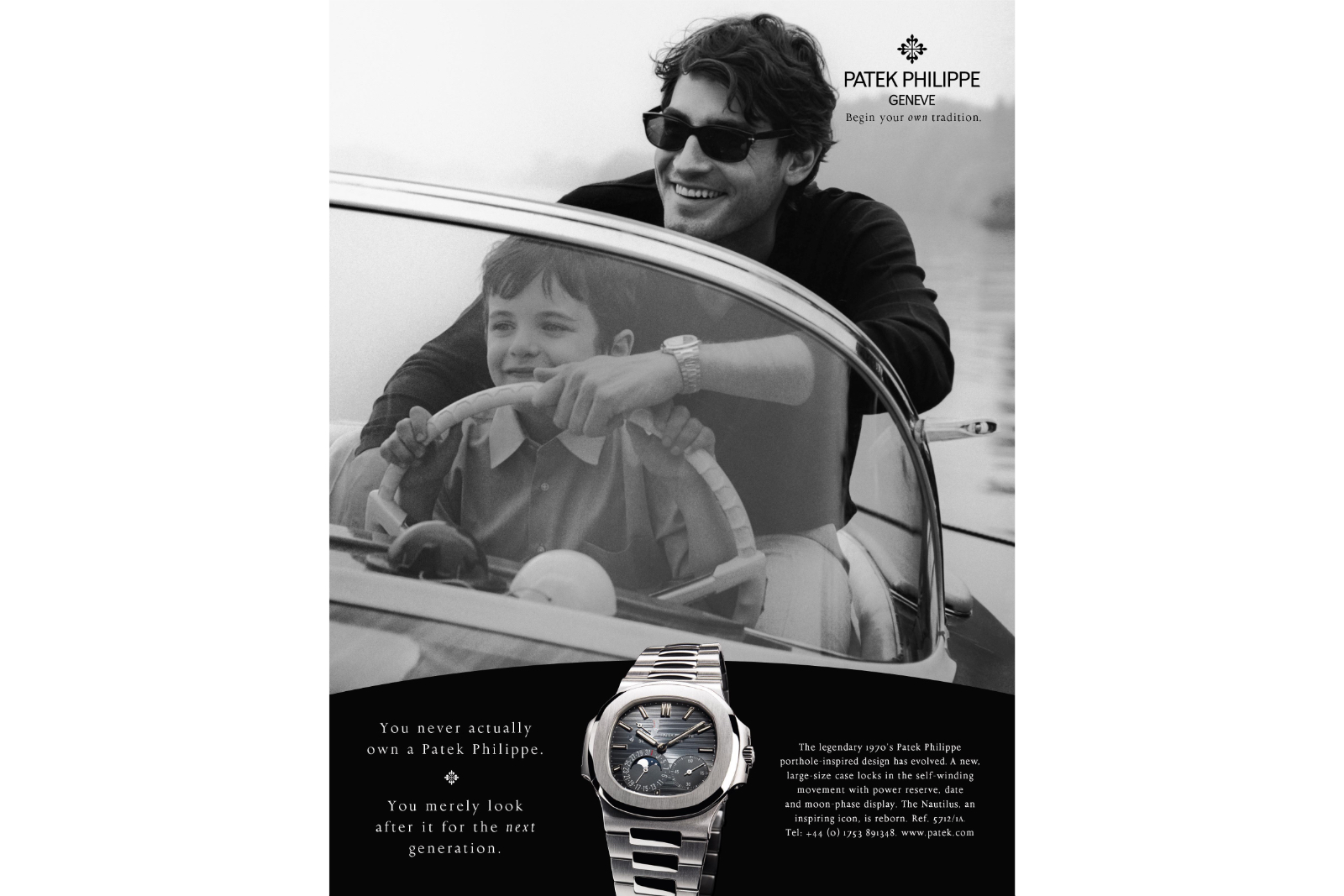

“Begin your own tradition” 1996 ad campaign. Image – Patek Philippe

Consumer research revealed a consistent insight: high-net-worth individuals were disengaged by celebrity-driven messaging. When presented with endorsements, the question was often the same: “What about me?” Rather than aspire to someone else’s life, these clients wanted to see their own values reflected. They were seeking emotional connection, not vicarious identity.

Tim Delaney, the agency’s principal, distilled this into a new concept, “begin your own tradition”. The first advertisements featured no watch at all. Instead, they showed quiet, idealised moments between parents and children, a father and son, a mother and daughter, framed in soft light, their expressions captured with editorial intimacy. The product appeared only in a caption or as a separate inset. The focus rested on the relationship between generations, with the watch serving as its quiet marker. As Mr Delaney recalled in interviews, the goal was to speak to a sense of permanence and private meaning without theatricality.

The 1997 ad campaign. Image – Patek Philippe

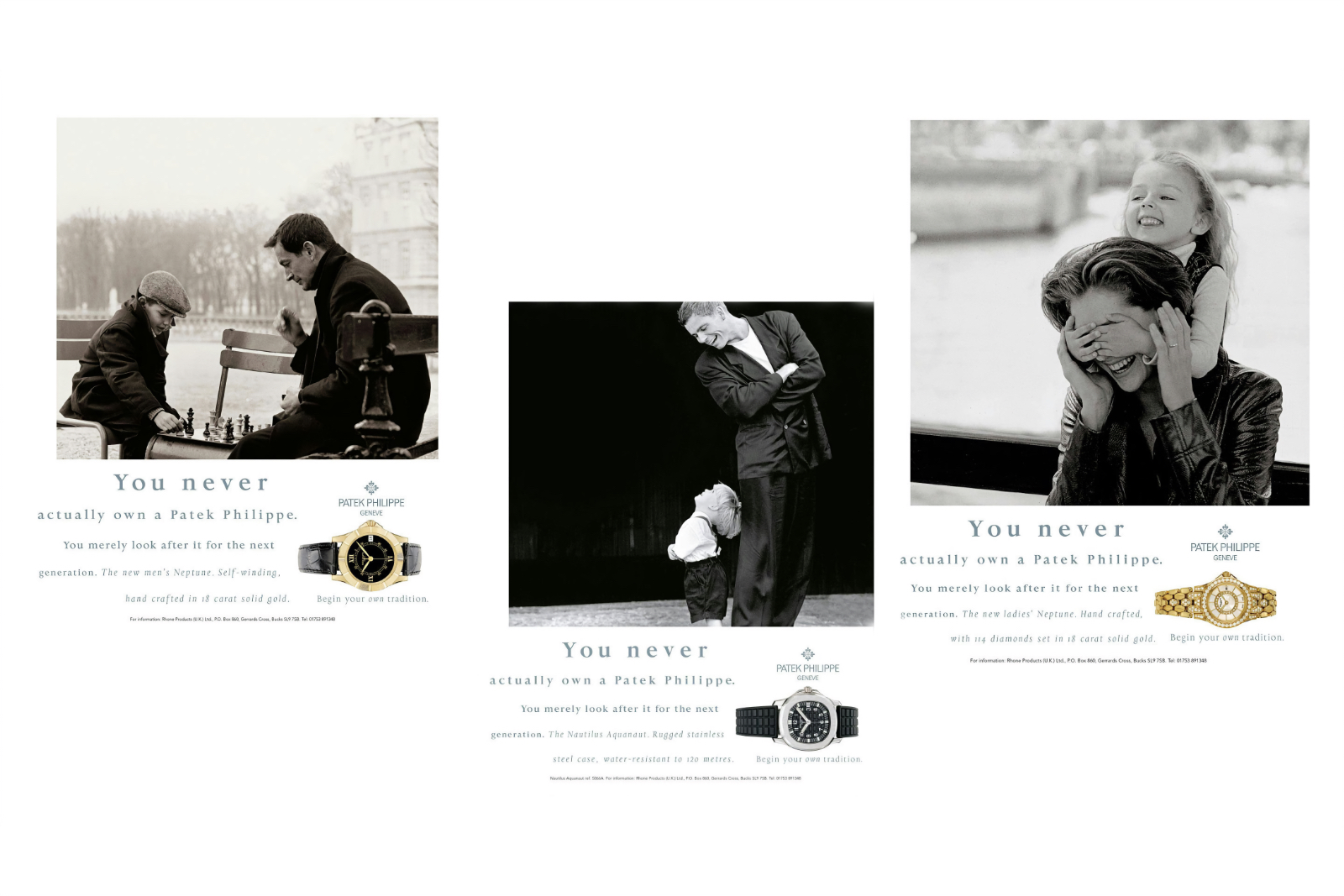

In early 1997, the campaign introduced a line that would define the brand’s voice for decades to come:

“You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation.”

The message reframed luxury as stewardship. Ownership became a form of responsibility, and the watch a vessel of continuity, less a symbol of achievement than an expression of long-term connection. The campaign offered a gesture toward meaning, inviting buyers to see the purchase as part of a larger personal history.

Throughout this initial phase, the campaign remained visually consistent: natural light, muted color palettes, and understated styling. The watch was never worn in the main images. The emphasis stayed with the people, the moments, and the emotion they carried. As Patek Philippe: The Authorized Biography confirms, this shift in tone represented the most significant evolution in the brand’s communication since the early 20th century.

The campaign also avoided overexposure. Patek Philippe placed its ads in upscale publications with high reader loyalty, The New Yorker, Financial Times, The Economist, and titles that spoke to depth over volume. There was no rotation through seasonal slogans or novelty-driven copy. Each execution felt part of the same, continuous idea.

“Who will you be in the next 24 hours” ad campaign. Image – Patek Philippe

For women, the campaign developed its own branch beginning in 1999, coinciding with the launch of the Twenty-4 collection. These ads retained the core message but shifted tone slightly to reflect independence, modernity, and personal meaning outside the context of family. This branch of the campaign was one of the first in luxury watchmaking to speak directly to women without condescension or fashion framing.

What emerged in these years was a campaign that shaped the brand’s entire voice, capable of carrying new models, evolving in detail, and returning consistently to its foundation: a watch as a connection between people, across time.

Modernisation and Market Control (2006–2020)

As digital platforms reshaped communication and watch collecting entered a global resurgence, luxury advertising underwent another transformation. The 2000s and 2010s were defined by multimedia campaigns, video content, social media storytelling, and influencer partnerships. Many watch brands shifted toward immediacy, chasing relevance through collaborations, endorsements, and seasonal imagery aimed at younger audiences.

Patek Philippe continued on its own course, choosing to refine the structure of its existing campaign instead of adopting rapid content cycles. In 2006, a subtle but meaningful visual change was introduced: watches began appearing on wrists in the photographs. The first execution of this updated format was shot by Peter Lindbergh and featured the Nautilus ref. 5712. This marked the first time product and narrative were visually integrated. The emotion remained, and the context expanded. The product became part of the narrative frame.

2006 ad campaign featuring photography by Peter Lindbergh. Image – Patek Philippe

This visual update allowed the campaign to carry more product visibility while retaining its tone. The framing stayed consistent, natural light, candid composition, and the absence of theatrical styling. The hands in the photograph were still the primary subject; the watch was present, but never dominant. It became part of the gesture, secondary to the moment it helped express.

The messaging did not shift. The original tagline – “You never actually own a Patek Philippe” – remained unchanged. What evolved was the ability to communicate both intimacy and product simultaneously, without disturbing the balance.

The 2019 “The Art of Watches Grand Exhibition” in Singapore. Image – Patek Philippe

Beyond the campaign, Patek Philippe deepened its presence through educational and cultural initiatives. The company’s exhibitions, previously concentrated in boutique environments, scaled into major public events.

The Watch Art Watch Grand Exhibition took place in New York (2017), Singapore (2019), and Tokyo (2023) – and in Milan come 2026 – offered visitors an immersive experience in horological history, with archival pieces, watchmaking demonstrations, and thematic rooms recreating aspects of the manufacture.

According to Patek Philippe: The Authorized Biography, these exhibitions were conceived as brand showcases and as carefully designed encounters with continuity and craft. They served a dual purpose: to reinforce heritage and to create long-term emotional engagement.

At the same time, the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva became a strategic asset. Visitors experienced the full arc of watchmaking, from 16th-century timepieces to the most complex creations of the modern era. This material presence offered an answer to the digital saturation around it. While others built stories for screens, Patek Philippe built rooms, displays, and timelines.

Entrance of the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva. Image – Patek Philippe

In digital environments, the brand remained selective. Its website functioned less as a retail hub and more as a curated archive. Social media was handled with restraint, fewer posts, longer intervals, and no attempt to mimic trend-driven behavior. Tone across channels remained consistent: composed, focused, and grounded in continuity.

This period also reinforced a broader strategy: Patek Philippe tightened control over distribution, limited production, and emphasised the importance of family ownership. These choices, while operational in nature, shaped the narrative context of its communication. The story remained clear, this was a brand that moved at its own tempo.

By 2020, the “Generations” campaign had run for nearly 25 years. It remained visually recognisable, emotionally resonant, and commercially effective. No other luxury watch brand had maintained a single campaign for so long. And no other had positioned permanence itself as the product being offered.

Present and Ongoing (2021–2025)

The 2020s have introduced new dynamics in how luxury is communicated. Digital acceleration, collector communities, and rising transparency across markets have reshaped the landscape. Brands now operate across overlapping channels, where watches circulate in both physical and digital environments, and perception is shaped by rhythm, exposure, and narrative reach.

Patek Philippe continues to navigate this terrain with measured intent. Its campaign remains visually and verbally consistent, structured around the same format introduced in 1996. The tagline still appears in each execution, the imagery continues to depict quiet exchanges between generations, and the composition maintains its deliberate pace. The endurance of this approach reflects a conscious decision to preserve coherence in an increasingly fragmented media environment.

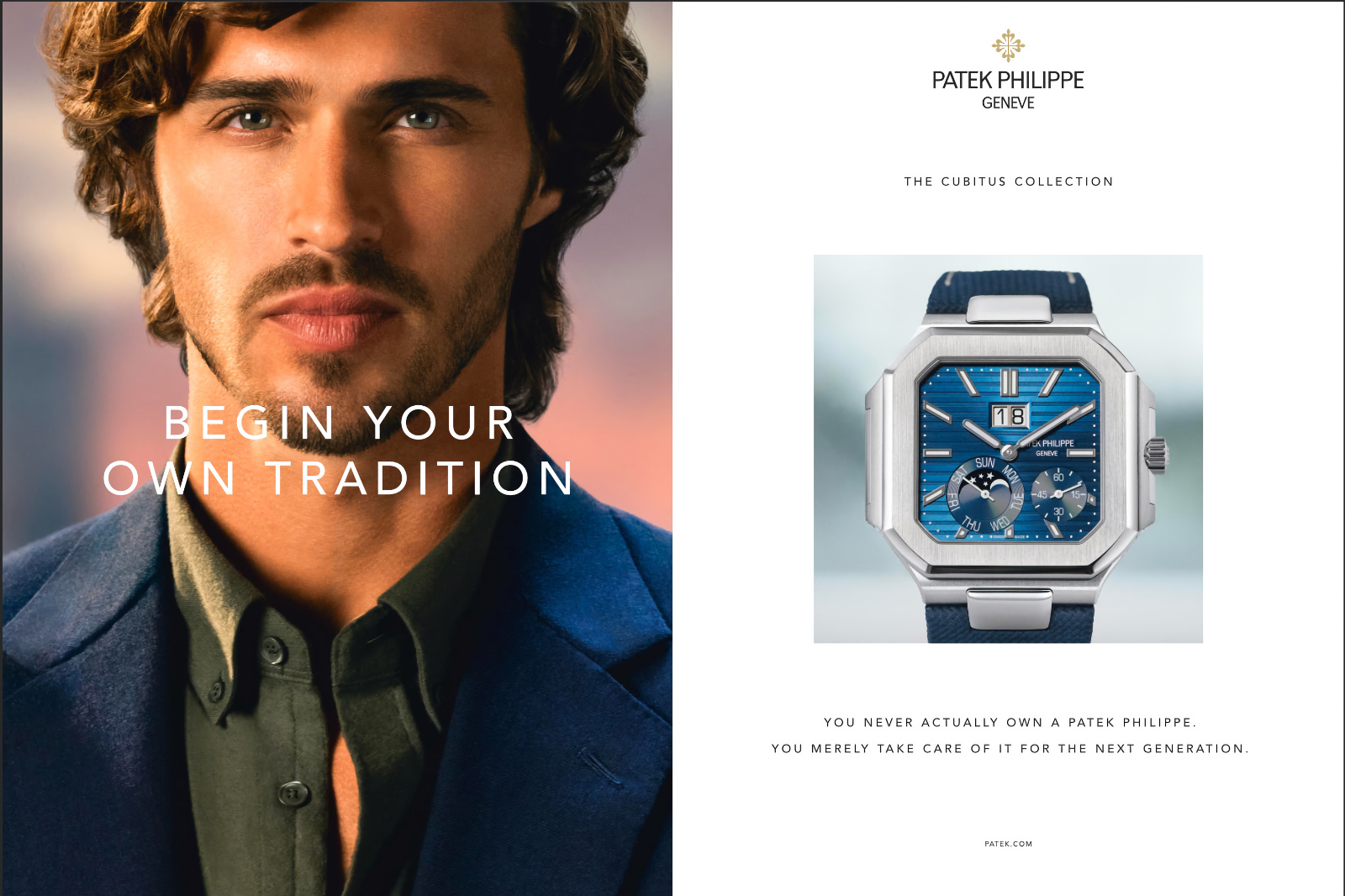

2025 ad campaign featuring the new Cubitus collection. Image – Patek Philippe

Recent advertisements have introduced broader casting and contemporary settings, reflecting cultural shifts while remaining grounded in the brand’s language. These adjustments occur gradually and with precision. This steadiness has become a signature trait, less about resisting change than shaping it slowly from within.

Public exhibitions and curated environments have also continued to evolve. These presentations blend archive, craft, and current production in settings designed to foster emotional alignment. In parallel, the company has refined the conditions under which its watches are encountered. Over the past two decades, Patek Philippe has concentrated its retail presence through a select network of boutiques and trusted partners. This strategy aligns setting with message, allowing each point of contact to reflect the brand’s principles of privacy, coherence, and long-term significance.

Boutiques are conceived as environments of intent. Materials, architecture, and spatial rhythm shape the encounter with care and clarity. The pace reflects the brand’s philosophy, time is approached with consideration and care. In a culture shaped by immediacy, this structure enhances the perception of rarity through rhythm, presence, and control.

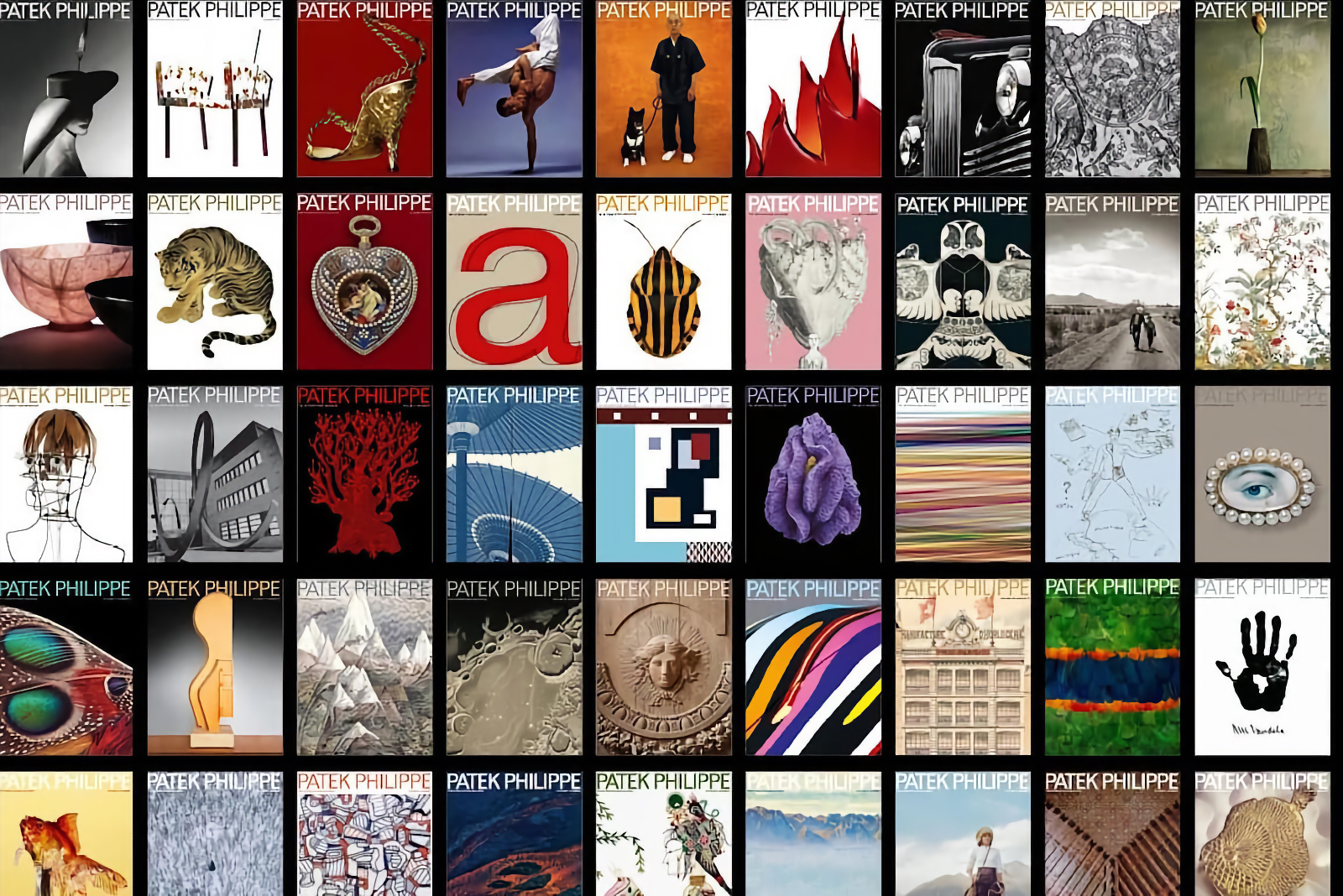

Collage of Patek Philippe magazine covers. Images – Patek Philippe

At the collector level, engagement remains personal and curated. Relationships are maintained through private communication, tailored events, and long-standing editorial vehicles. Patek Philippe, the brand’s in-house magazine, was first published in 1996 and continues to offer a carefully controlled platform for storytelling, education, and cultural positioning. Conceived by Philippe Stern, the magazine supports the continuity of the brand’s voice and extends its narrative across generations.

The language of the campaign has seen gentle refinements. Captions now refer more directly to life events, weddings, graduations, family milestones, always in relation to memory and continuity. A watch is presented as a vessel of meaning, shaped by the experiences that surround it.

The “Generations” campaign is now approaching thirty years of continuous use. It carries the weight of the brand’s worldview across evolving demographics and expanding markets. Through this continuity, it has become one of the most enduring campaigns in contemporary luxury, a framework through which Patek Philippe continues to express value, identity, and time.

Conclusion

Patek Philippe’s marketing evolution traces a line of continuity that mirrors the way its public perceives its watches, precise, unhurried, and carefully maintained. Across changing eras, shifting media, and expanding markets, the brand has preserved a consistent approach to communication: clear in tone, restrained in style, and anchored in long-term thinking.

Each phase, from royal commissions and world exhibitions to generational messaging, has expressed the same idea through evolving forms. The brand defines value on its own terms, allowing meaning to grow through coherence and repetition.

Across poster art, editorial campaigns, curated exhibitions, and digital environments, Patek Philippe has remained steady in its messaging. It speaks through rhythm and structure, allowing perception to accumulate through alignment of image, language, and experience.

This clarity grows through consistency. Every decision in voice, format, and setting reinforces the product’s intended role, a possession shaped by purpose and framed with intent. Like its mechanical craft, the brand’s communication is designed to endure, holding its shape across generations.

Back to top.