Inside the Watchmaking Journey of Dann Phimphrachanh

The newest candidate for the AHCI.

In the world of independent watchmaking, Phimphrachanh – pronounced “fin-fra-chan” – is a name worth learning. Born in France, Dann Phimphrachanh is a Portuguese citizen with Laotian heritage who produces watches in Switzerland. That multicultural heritage that informs his approach to horology, personified by the Seconde Vive, his first wristwatch.

The Phimphrachanh surname, inherited from his Laotian grandfather, a political figure in Laos, speaks to this lineage, but Dann’s professional and personal identity is firmly rooted in Portugal. After training in Lisbon’s watchmaking school and working at traditional Swiss watch brands, Dann set out to build his first watch on his own terms: by hand, with minimal industrial tools, and a commitment to preserving classical methods in a modern context.

In a world where “independent watchmaking” can sometimes feel like just another label, Dann reminds us what it really means. The Seconde Vive, the result of years of solitary work, is both a technical achievement and a reflection of a deeper pursuit, a journey shaped by tradition, silence, and the slow mastery of time itself.

The Seconde Vive

Origins

When Dann first left for Switzerland, he carried with him an image shaped by the glossy pages of watchmaking magazines, a world where the watchmaker was portrayed as a solitary figure, pursuing perfection in a quiet, idyllic workshop. “It was that image I went looking for,” he recalls.

Reality, of course, was more complex. Although he was warmly welcomed into a family-run brand that remains close to his heart, the deeper he moved into the world of Swiss horology, the more he encountered quiet disillusionment. The romantic ideal he had built from afar did not always survive contact with the modern realities inside the great houses. Some traditions endured; others had worn thin.

Yet Dann’s commitment remained firm. When asked whether he sees himself as an heir to tradition or a pioneer forging a new path, he answers without hesitation. For him, being a watchmaker means standing humbly on the achievements of those who came before.

“Watchmaking isn’t just a passion,” he says. “It’s also work that demands effort, study, and the right tools.” His personal aim is clear. He doesn’t want to reinvent for the sake of novelty, but to inhabit horology fully, carrying its spirit forward with admiration and conviction.

Process, Solitude, and Self-Discovery

Since 2018, Dann has worked almost entirely alone, a choice that has profoundly shaped his approach. Solitude, far from being a burden, became an ally. It taught him not only the real timescales of creation but also the value of allowing ideas to evolve without external pressure.

“Solitude is a wonderful place when you believe in what you’re doing,” he says, “Every step becomes human, and the journey matters as much as the destination.”

Study for main-plate. Image – Dann Phimphrachanh

Isolation forced him to rethink everything, from how he structured his atelier to how he prepared himself mentally for the rigours of creation. School, he acknowledges, provided the essential technical foundations. But solitude became his truest teacher.

In his daily work, writing has become an indispensable ritual. Before and after each complex operation, he takes the time to write, a way of channelling the intellect and preserving joy in the process. Different phases of watchmaking demand different mental postures. When designing mechanisms or calculating gear ratios, he engages his intellect fully. But when sketching freehand or filing bridges, he deliberately quiets the analytical mind, allowing instinct to take over. Writing acts as a bridge between these contrasting states, a thread of coherence in a demanding craft.

The Architecture of the Seconde Vive

Describing the movement of the Seconde Vive isn’t easy, even for its creator. Dann didn’t begin with strict aesthetic rules; instead, he let instinct and handwork guide the forms, aiming for a feeling of depth, a movement that fills its space with natural balance.

Technical needs like working angles and clearances shaped the calculations behind it, but visually, the structure grew on its own terms. As he puts it, “I had no intention in the forms, my only goal was to feel a sense of depth and to have a movement that filled the case.”

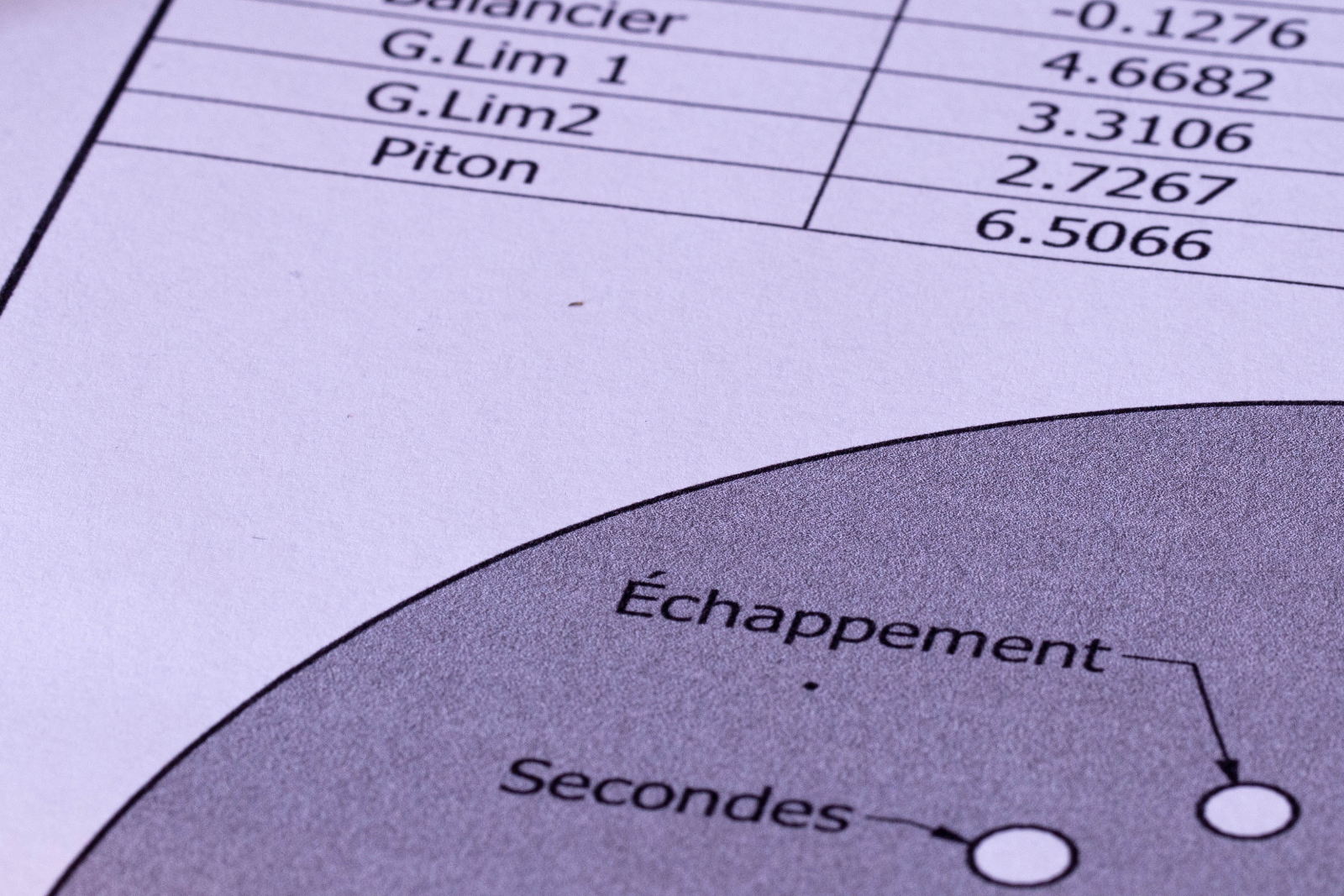

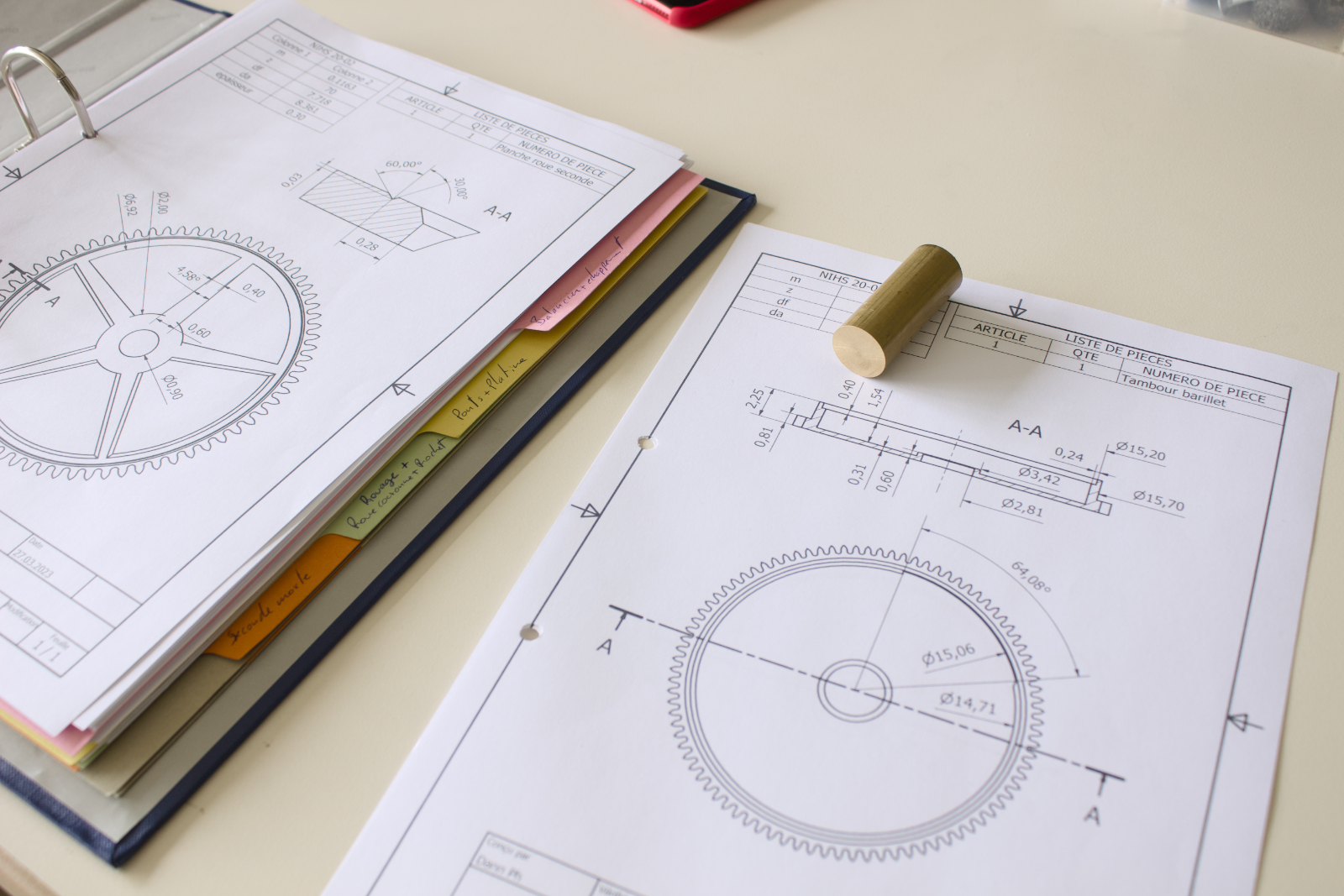

Planning components. Image – Dann Phimphrachanh

At the heart of the watch lies the Seconde Vive, a complication born from both personal need and creative drive. Dann sought to assert his legitimacy as a watchmaker, to show through mechanical function, not style alone, that he belonged among the craft’s true practitioners.

As a graduate of the Lisbon watchmaking school who arrived in Switzerland with a sense of impostor syndrome, creating a visible, animated mechanism was a way of claiming space through craft. At the same time, he wanted to create something anyone could understand: an animation slow enough for the eye to follow, yet lively enough to hold attention.

Working on a minute pivot. Image – Dann Phimphrachanh

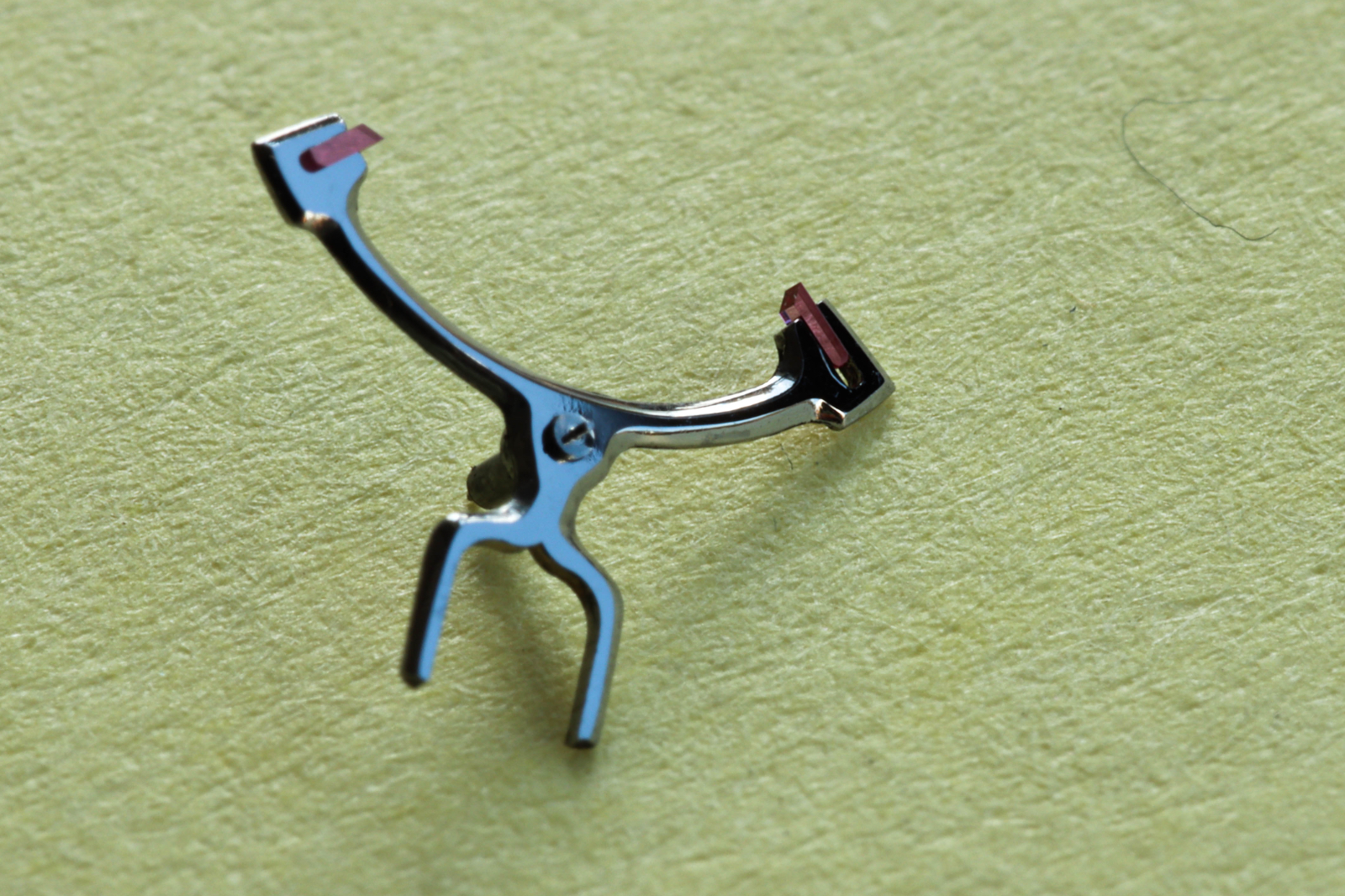

Seconde Vive, translating as “lively seconds,” reflects this intent. The hand jumps visibly, but the mechanism is not a pure deadbeat seconds system. Instead, the Seconde Vive celebrates motion for its own sake, offering a mechanical rhythm that feels alive, immediate, and engaging, without necessarily serving a chronometric function.

It is, as Dann puts it, “a horological wink”, a mechanical delight built for its own sake. The gear train and escapement visible on the dial side are entirely independent from the main timekeeping gear train, which quietly reveals itself on the reverse.

The seconds anchor that will engage the Reuleaux cam. Image – Dann Phimphrachanh

Technically, the seconds mechanism multiplies the motion of the minute hand by a factor of ten, then uses a triangular cam, inspired by the geometry of the Reuleaux triangle, to generate 30 steps per minute. This is then doubled with a custom anchor to achieve 60 discrete jumps per minute. It was a solution chosen not only for its rhythm but because the motion could be perceived and appreciated by anyone, regardless of horological training.

Part of this technical exploration led Dann to the geometric principles of the Reuleaux triangle, a shape known for maintaining constant width during rotation, a property that allows for highly controlled and consistent motion. In engineering, the Reuleaux triangle has been used in applications from rotary engines to precise cam systems, and although rarely seen in traditional watchmaking, its potential for managing torque and minimising friction intrigued Dann.

He saw in it a mechanical language that paralleled his own aims for the Seconde Vive: to create a visible, lively motion that felt smooth, rhythmic, and naturally coherent within the watch’s architecture. His thinking echoes the spirit of Derek Pratt, who drew inspiration from rotary geometries like the Wankel engine when developing his own escapements, seeking not just precision, but elegant mechanical efficiency.

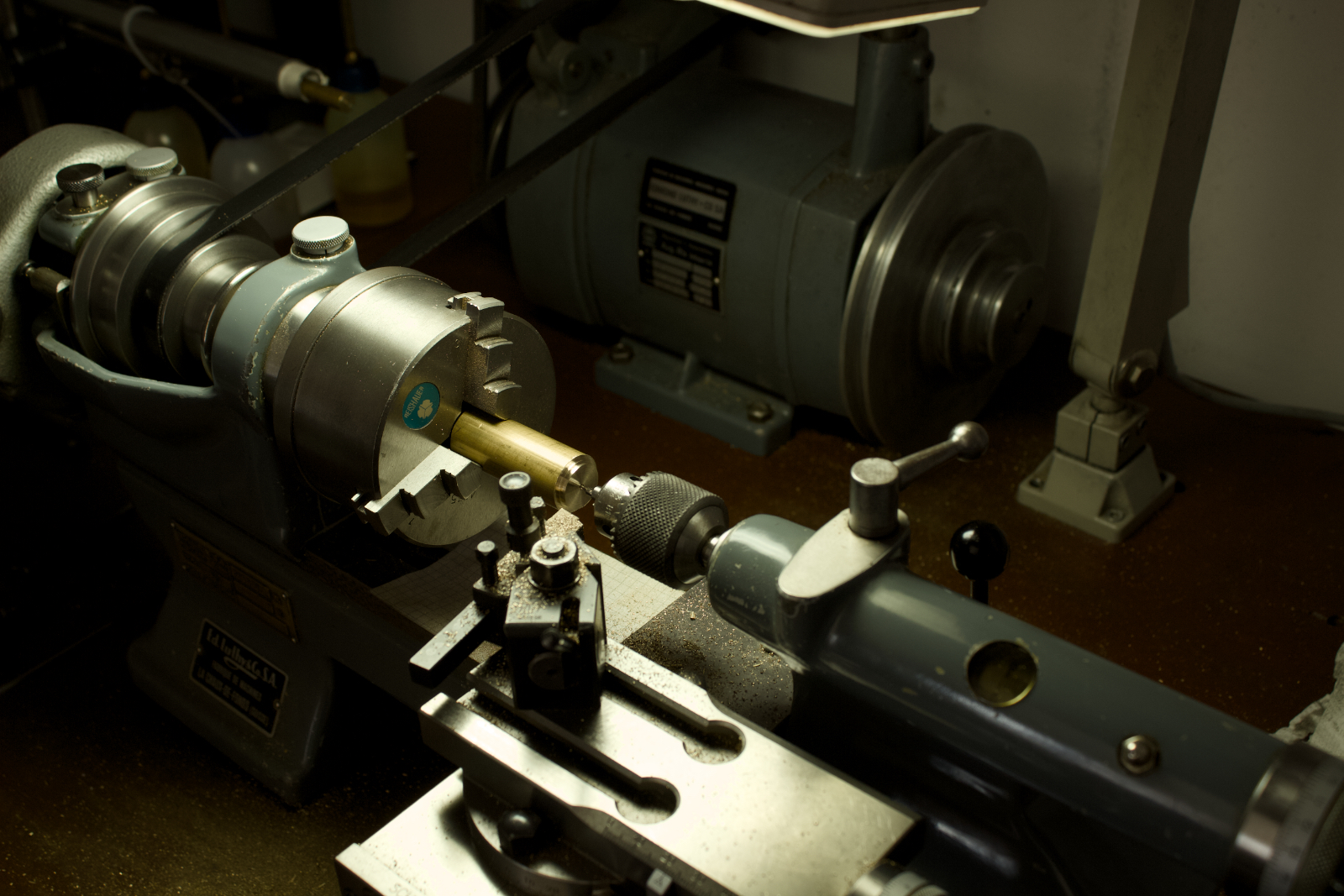

Lathe work in the atelier. Image – Dann Phimphrachanh

Bringing the Seconde Vive to life also meant facing the practical realities of independent work. Although Dann machines all the mechanical components himself, he chose to rely on commercially available barrel springs and balance springs, a decision born from pragmatism rather than compromise. Manufacturing these components is viable only at industrial scales, and sourcing them ensures that the watch remains serviceable for generations to come.

Budget constraints, too, shaped his approach. Every tool and machine in his workshop had to be chosen carefully, often requiring restoration rather than replacement.

“Living time with passion,” he says, became the philosophy: working slowly, intentionally, as artisans once did, with an intimate knowledge of every machine’s temperament. This spirit of resourceful independence is deeply embedded in the Seconde Vive itself, not merely in its aesthetics or mechanics, but in the choices that made its existence possible.

Finishing tools. Image – Dann Phimphrachanh

Friction, as always, proved the greatest adversary. Every surface, pivot, and gear had to be painstakingly finished to minimise energy loss without compromising durability. Over time, by mastering the nuances of his own machinery, Dann learned to machine consistently within tolerances of five microns, a precision made possible by modern methods, but pursued with the patience and hand-focused spirit of the early masters he admires.

Material choices followed the same philosophy of longevity and repairability. He chose maillechort, or German silver, for the plates and bridges, hardened S20AP steel for structural parts, and silvered steel for the springs, all left untreated to preserve their ability to be refinished or repaired generations from now. The case itself was crafted in durable 316L stainless steel, completing the ensemble.

Spiral before applying terminal curves. Image – Dann Phimphrachanh

When the Seconde Vive finally came to life for the first time, it was far from the triumphant moment he had imagined. “Honestly, the first time it ran, it was a huge disappointment,” he admits. The seconds hand hesitated instead of snapping cleanly forward, the system consumed too much energy, and the overall design fell short of his hopes. It took four radical reworkings, including three successive reductions in pivot size and dozens of subtle refinements, before the movement reached the fluidity he had envisioned.

Fittingly, the true moment of satisfaction came not in the workshop, but on the forest trails and sidewalks of his town near Yverdon-les-Bains, where he tested two prototypes while riding his bicycle. Seeing both mechanisms survive real-world vibrations, ticking, jumping, alive, finally brought the project full circle.

When asked whether access to CNC or EDM machines would have changed his process, Dann simply shrugs: “If I had wanted to work with CNC machines,” he says, “maybe I wouldn’t have chosen watchmaking.”

Beyond the Seconde Vive

Fresh from the completion, and the first public presentation, of his debut creation as a candidate at the AHCI exhibition in Geneva, where the Seconde Vive was met with great success and a promising order book, Dann’s mind is already turning to quieter challenges.

Rather than rushing into new projects or chasing attention, his focus remains on laying solid foundations: creating a workshop environment that will safeguard his commitment to traditional, hand-crafted watchmaking.

“My concerns today are about creating the right conditions to guarantee my loyalty to traditional watchmaking and handcraft,” he says. “One step at a time. I don’t want to spread myself thin.”

Looking ahead, he feels naturally drawn toward the idea of developing new complications, though he recognises that true creativity resists rigid planning. “If the Seconde Vive taught me anything,” he reflects, “it’s that it’s impossible to predict the details. But I’m looking forward to the day the first drawings of the next piece appear”.

The Future of Artisan Watchmaking

As more and more independent watchmakers emerge, Dann remains clear-eyed about the dangers of marketing co-opting the word “independent.” “If it’s not already the case, marketing will use ‘independent’ as a banner for as long as it remains profitable,” he says with a wry smile. “That’s the nature of marketing.” Yet he trusts that true connoisseurs, those who seek authenticity, will see beyond the labels.

Polishing of a ruby chaton. Image – Dann Phimphrachanh

For Dann, the spirit of independence is essential. Looking at the history of horology, he notes that even the most iconic creations from the great watchmakers bear the unmistakable mark of a single creator’s vision, not the efforts of an anonymous department. “Independent watchmakers today have created more true DNA, more real style, than millions spent in design departments over the past fifty years,” he reflects.

Guilloché decoration work on the dial. Image – Dann Phimphrachanh

What he hopes to see in the future is simple: more watches that are profoundly personal. “Watchmaking is like dance,” he says. “It’s all about DNA, about style.” If a creation can marry technical mastery, cultural richness, and personal expression, Dann is ready to be won over.

For now, Dann’s focus remains firmly on building his own path. Solitude, he knows, is not an easy companion, but it is essential to the way he works. “Maybe someday,” he muses, when asked whether he might one day share his methods. For the moment, though, creation demands all his attention: a quiet dialogue between hand, mind, and time, far from the noise of the world.

Time as the Final Lesson

Of all the lessons Dann drew from creating the Seconde Vive, one stands above the rest: the unpredictable nature of time. Not time measured in seconds and hours, but the lived experience of creative time, the slow accumulation of thought, the sudden flashes of intuition, the long, patient work of making and remaking.

Sometimes, despite all calculations, a perfectly crafted part would feel out of place. At other times, a less meticulously finished piece would prove to be the truest fit. He learned to let the work speak for itself, trusting his morning reflections, when the light was clear and the mind sharper, to guide his final decisions. “It was each morning, in that one clear moment,” he says, “that I knew whether what I was doing truly resembled me.”

In the end, the Seconde Vive was not shaped solely by the techniques Dann had acquired during nearly two decades in haute horlogerie, working at firms such as Daniel Roth, in the complications department at Bulgari, at Parmigiani Fleurier, Greubel Forsey, and Jaeger-LeCoultre. It grew from something quieter and harder to measure: the ability to listen, to doubt, to wait, and to live the time it takes to create something that feels alive.

Back to top.