Knowledge: Popes and Precision – Papal Clocks and Watches

A pair of Patek Philippes, Vacheron Constantin and one from the Jura.

With the recent election of Pope Leo XIV—the first American and Augustinian pontiff—a rare opportunity arises to revisit one of the most intriguing intersections between horology and the papacy. While much attention has historically centered on Pope Leo XIII’s Jubilee in 1888, when Patek Philippe crafted commemorative watches for the occasion, the relationship between watchmaking and the Vatican stretches further back, rooted in the values and vision of Patek Philippe’s co-founder, Antoine Norbert de Patek.

A devout Catholic and Polish émigré, Patek viewed watchmaking not merely as a commercial enterprise but as a moral and cultural calling. His personal faith and longstanding connection to the Catholic Church helped shape the company’s enduring ties to religious institutions, most notably the Vatican. This ethos of sacred precision and spiritual patronage found material expression in a number of papal commissions, the most prominent of which emerged during the reign of Leo XIII.

Complementing Patek Philippe’s contributions, Vacheron Constantin also played a significant role in this narrative. In collaboration with Parisian retailer Ratel, they produced devotional timepieces that transcended mere functionality, serving as instruments of spiritual reflection. These watches, rich in symbolism and craftsmanship, further exemplify the deep connections between horology and the papacy.

Papal Precedents: The Watches of Pius IX

Before Leo XIII’s Jubilee, the tradition of papal horology had already begun to take shape under Pope Pius IX, a figure who, despite his polarising legacy, defined much of the Catholic Church’s institutional identity in the 19th century.

Born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti in 1792, he came from a devout yet intellectually open noble family in Senigallia. Ordained in 1819, he rose swiftly through the ecclesiastical ranks, eventually becoming Cardinal in 1840. His election to the papacy in 1846 ushered in a pontificate that would become the longest in Church history, lasting until 1878.

Portrait of Pope Pius IX by Giovanni Orsi (1847). Image – Wikipedia

Initially welcomed as a reformer, Pius IX’s early policies, including a general political amnesty and efforts to create a lay consultative council, stirred hope among liberals. But the revolutionary upheaval of 1848, which saw the assassination of his Prime Minister and the temporary collapse of papal governance, led to his retreat into conservatism.

Patek Philippe & Co. No. 27033 (1866/1867). Image – Patek Philippe

After returning to power with French military support, Pius IX grew increasingly authoritarian, aligning with Austria and resisting the unification of Italy. By 1870, he had lost control of the Papal States and declared himself a “prisoner in the Vatican,” rejecting the Italian government’s offers of symbolic sovereignty.

Patek Philippe & Co. No. 27033 (1866/1867). Image – Patek Philippe

Yet in spiritual and doctrinal matters, his influence endured. Pius IX proclaimed the dogma of the Immaculate Conception in 1854 and convened the First Vatican Council in 1869, which famously codified the doctrine of Papal Infallibility.

He fiercely resisted secularism and liberalism, culminating in the publication of the Syllabus of Errors (1864), a sweeping condemnation of modernist thought. To his contemporaries, he was often seen as a “Pope of Reaction”, a deeply pious but doctrinally rigid figure who shaped the Church’s defensive posture against a rapidly modernising world.

No. 27033, (1866/1867) movement. Half quarter-repeating on two gongs. Image – Patek Philippe

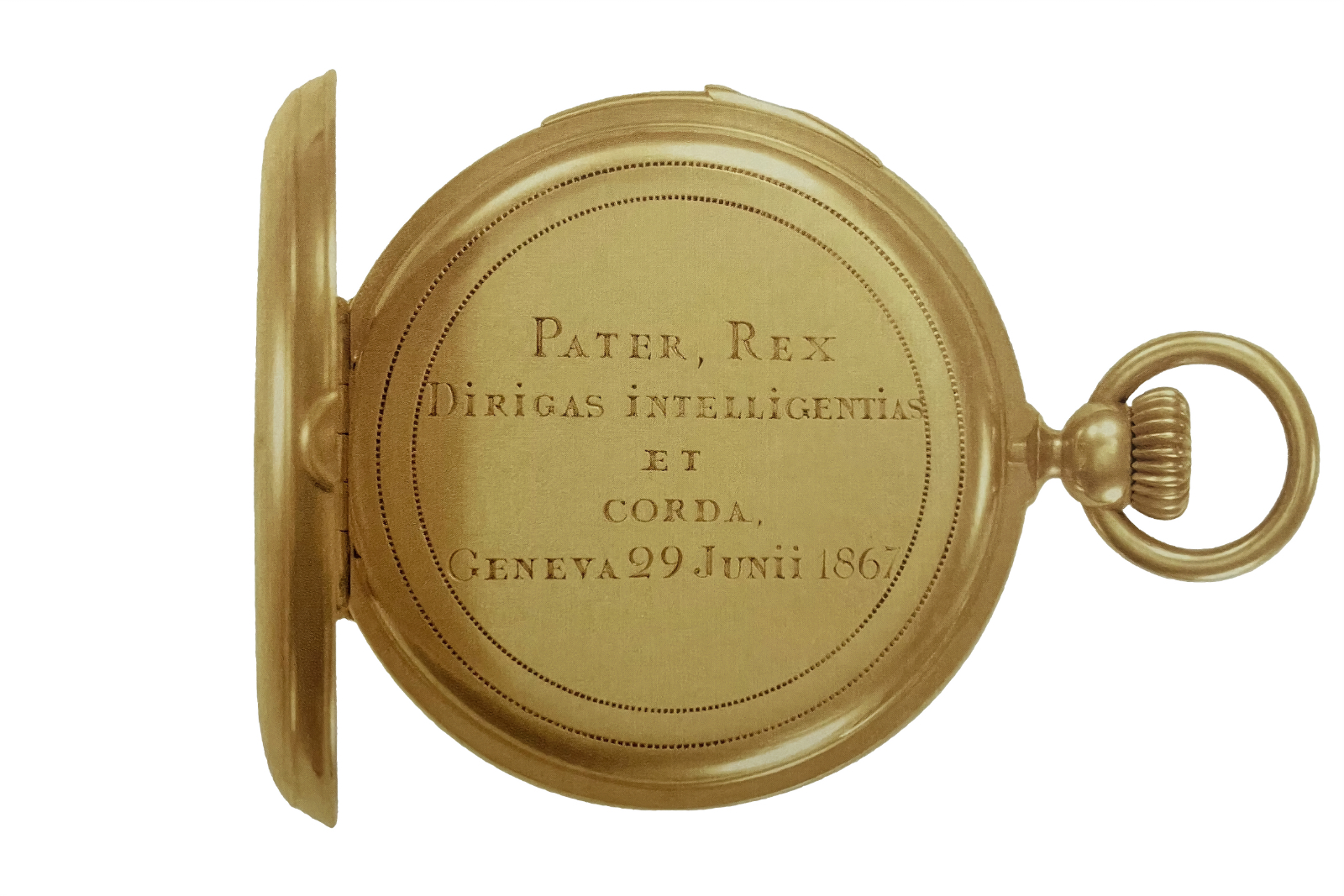

Amid this turbulent backdrop, two watches offer a rare glimpse into his papacy. One notable example is a yellow gold quarter-repeating keyless pocket watch, manufactured in 1866 and presented to Pius IX in 1867.

This watch, later sold at Christie’s in 2019, features a white enamel dial with Roman numerals, a recessed subsidiary seconds display, and a polychrome enamel depiction of the papal coat of arms on the back. The cuvette is inscribed with the Latin dedication “Pater, Rex, Dirigas Intelligentias et Corda,” reflecting a blend of spiritual symbolism and papal authority.

The piece, with No. 27033, represents one of the earliest known instances of Patek Philippe’s engagement with papal clientele.

No. 52334, (1876) cal. 18”’, manual. Image – Christies

A second significant example is a silver open-face pendant watch, manufactured in 1876 and sold the following year.

It features Roman numerals, the papal coat of arms, and an engraved cuvette bearing the inscription “PIO IX.PP., HELVETI CATHOLICI DD, MDCCCLXXVII,” indicating that it was a gift from Swiss Catholics.

No. 52334, (1876) cal. 18”’, manual. Image – Christies

These early timepieces signalled the papacy’s growing engagement with precision watchmaking and laid the foundation for the more elaborate tributes that would follow under Leo XIII. They reflect how even a pope best known for theological declarations and political intransigence engaged, directly or symbolically, with the mechanical ingenuity of his age.

The Jubilee of Leo XIII and His Patek Philippe Watches

Pope Leo XIII, born Gioacchino Vincenzo Pecci in 1810, ascended the papal throne in 1878 and governed the Church for twenty-five years until his death in 1903. Often referred to as the “Pope of Modernity,” Leo XIII sought to reconcile the Church with the intellectual and social realities of a rapidly changing world.

In stark contrast to his predecessor Pius IX, whose long reign had been marked by conflict with secular forces, Leo XIII adopted a more diplomatic and reform-minded approach. He attempted to ease tensions with European governments, notably seeking rapprochement with Germany after the Kulturkampf and with England through outreach to Anglicans. He also encouraged political engagement from Catholics, especially in democratic societies, provided it was anchored in religious values.

Pope Leo XIII (painting by Adolf Pirsch) – Wien Museum. Image – Wikipedia

Doctrinally, Leo XIII took strong positions on issues of modernity while attempting to steer the Church through them. He condemned freemasonry and unrestrained liberalism in the encyclicals Immortale Dei (1885) and Libertas (1888), while simultaneously engaging with the social consequences of industrialisation.

His 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, addressing the rights and conditions of labour, marked the birth of Catholic social teaching and earned him the epithet “Pope of the Workers.” In education and philosophy, he promoted a revival of Scholastic thought, particularly through the 1879 encyclical Aeterni Patris, and opened the Vatican archives to scholars for the first time in 1893.

Patek Philippe & Co. No. 56888 (1888/1901). Image – Patek Philippe

Amid this atmosphere of intellectual renewal and papal diplomacy, the Jubilee of 1888 marked the fiftieth anniversary of Leo XIII’s priestly ordination. The celebration prompted a wave of international tributes and ecclesiastical gifts, ranging from richly embroidered vestments to gem-set tiaras.

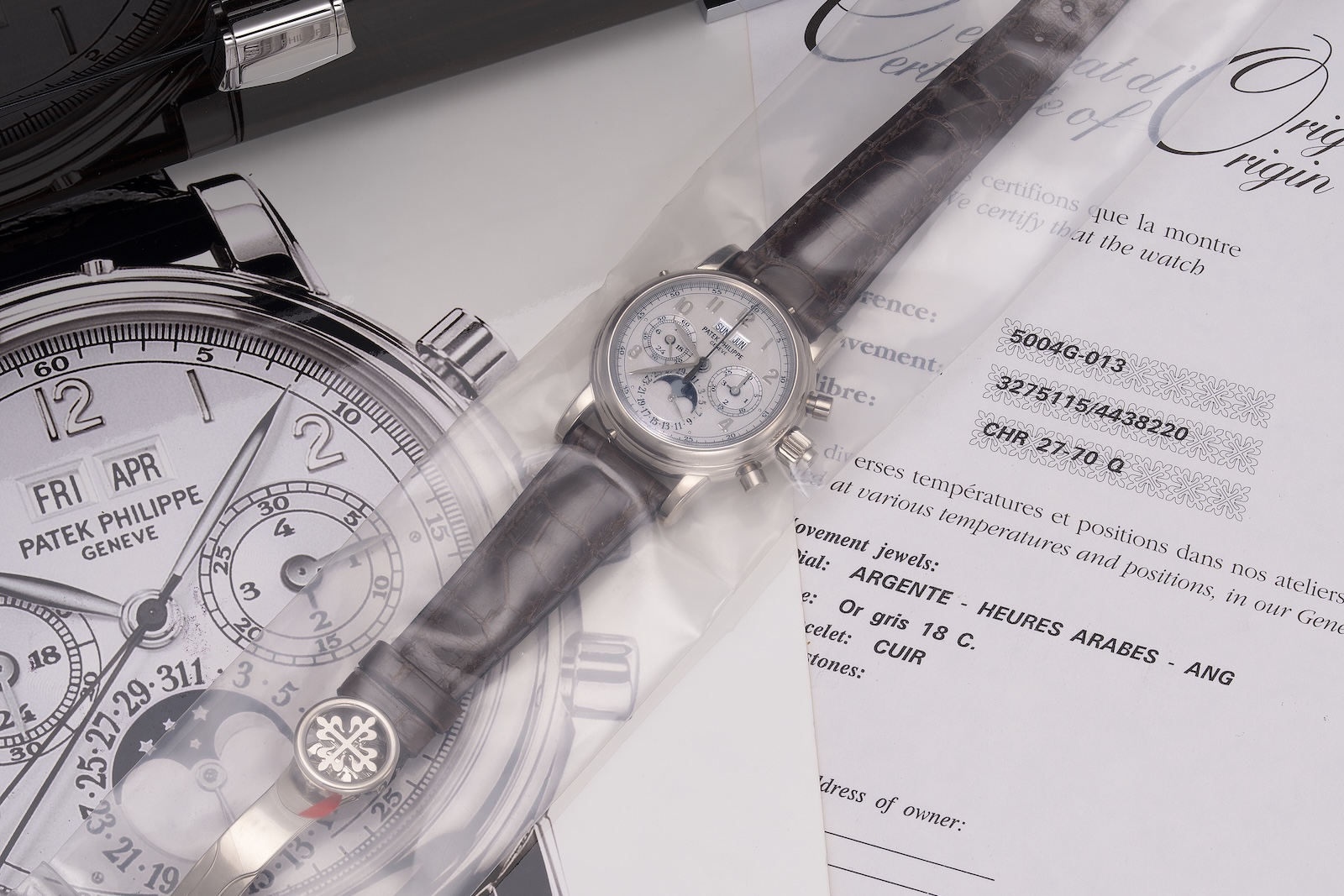

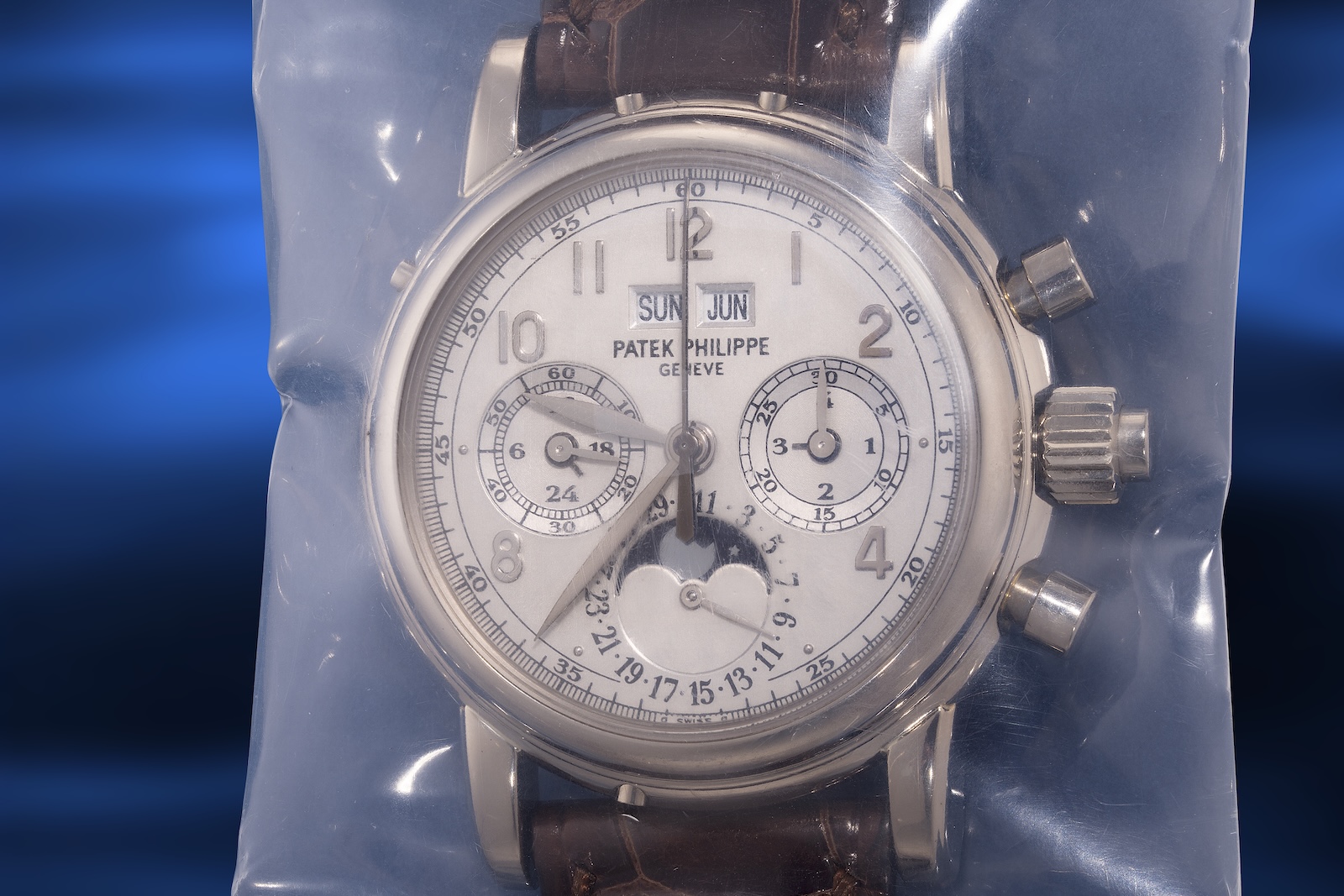

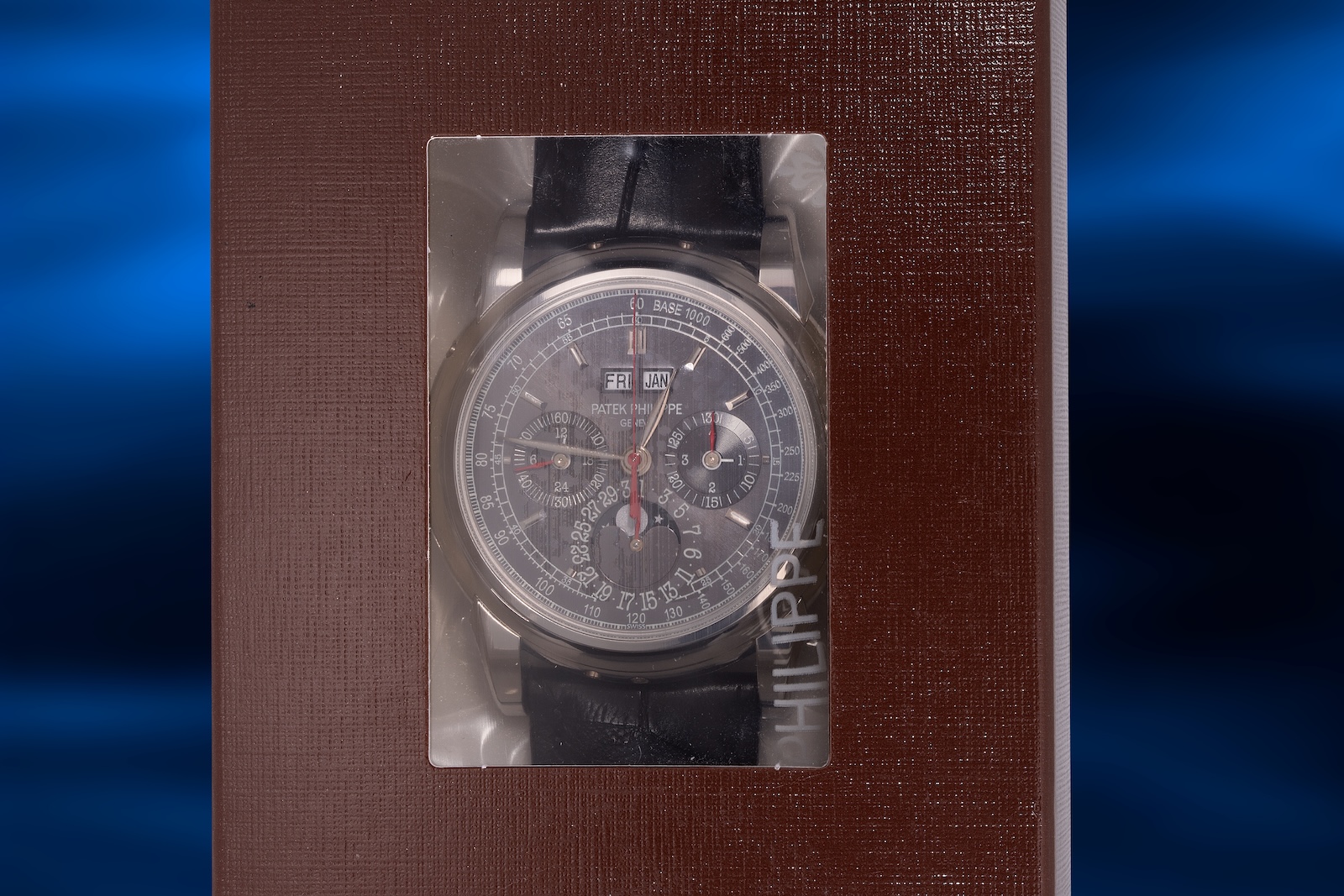

Swiss contributions, coordinated by a central committee, included both liturgical works and feats of horological ingenuity. Among these were at least two watches from Patek Philippe, each commemorating the pontificate.

Patek Philippe & Co. No. 56888 (1888/1901). Image – Patek Philippe

The first is a watch preserved today in the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva. It appears to have been produced to mark the tenth year of Leo XIII’s pontificate in 1888. The hunting-case, keyless-winding pocket watch was made between 1888 and 1901 and is crafted in silver and rose gold.

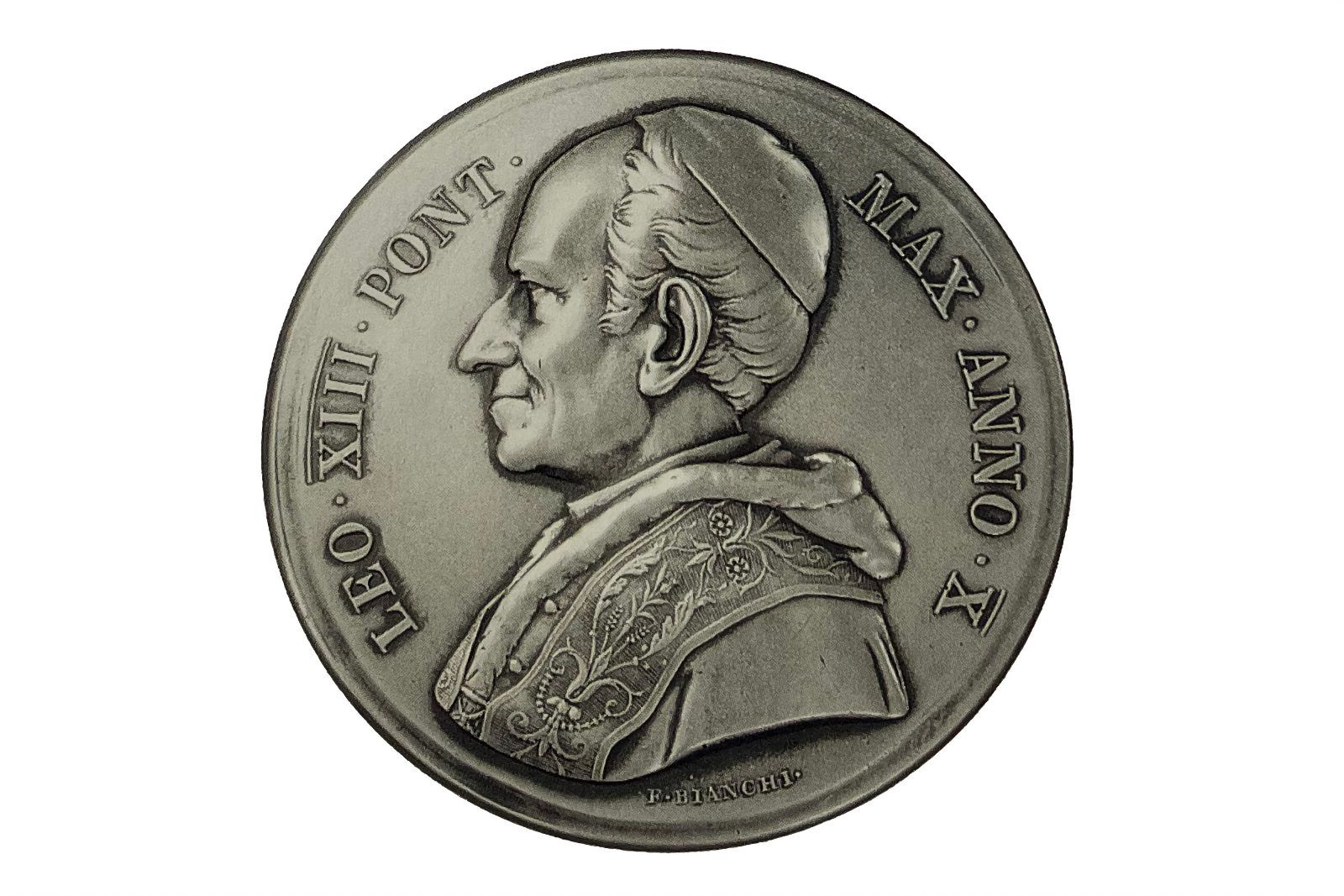

Its case and cuvette incorporate a medal by Francesco Bianchi (1842–1918), a Roman-born medallist who served as official engraver at the Pontifical Mint from 1876 until his death.

Detail of Francesco Bianchi’s medal (1842-1918). Image – Patek Philippe

Bianchi was responsible for all annually issued papal medals across the reigns of Pius IX, Leo XIII, Pius X, and Benedict XV. A student of the Academy of San Luca and the son of engraver Giuseppe Bianchi, he had earlier collaborated on the famed Porta di Gaeta medal for Pius IX and sculpted the Confession of Saint John of Lateran for the Vatican in 1851.

Known for his refined relief portraiture and classical aesthetic, Bianchi’s work was particularly suited to religious commissions. The medal used on this watch bears a formal profile of Leo XIII and commemorates his pontifical milestone, seamlessly merging ecclesiastical symbolism with Genevan craftsmanship.

Patek Philippe & Co. No. 56911 (1886). Image – Collectability

While the precise circumstances of the watch’s delivery remain unclear (with no documentation confirming whether it was officially commissioned, privately presented, or retained in Swiss hands) its rich iconography and liturgical overtones suggest it was conceived as a commemorative object, likely intended for Vatican display or formal tribute.

The movement was removed sometime after 1936, the date of its last recorded servicing. Today, the piece remains a centrepiece of the museum’s collection, embodying a rare convergence of horological artistry and papal history.

Patek Philippe & Co. No. 56911 (1886). Image – Collectability

In recent years, a second Patek Philippe pocket watch commemorating Pope Leo XIII’s Jubilee surfaced at Collectability, the American specialist Patek Philippe dealer. This silver open-face pocket watch, measuring 50 mm in diameter, was crafted in 1886 and sold in 1888. Its design closely mirrors the example housed in the Patek Philippe Museum.

The watch features a hand-chased and engraved bezel, a chased silver dial with engraved and enameled Roman numerals, and gold Louis XV-style hands. A distinctive rose gold turban crown adds a subtle flourish, identical to the crown on the museum’s example. The case back also showcases a silver medal with a profile of Pope Leo XIII, fashioned from Jubilee medals commemorating the tenth anniversary of his pontificate.

Unlike the museum piece, which is missing its original movement, this watch retains its complete original movement, number 56’911. An Extract from the Archives confirms the movement and case numbers, as well as the ‘chiselled case band and bezel, Leon XIII jubilee silver medal’.

While it’s unclear whether Pope Leo XIII personally wore or presented this watch, its craftsmanship and historical significance make it a remarkable artifact of papal horology.

Patek Philippe & Co. No. 56911 (1886). Image – Collectability

These two watches demonstrate how Leo XIII’s pontificate inspired commemorative timepieces that blended ceremonial gravitas with intimate craftsmanship. Though similar in design and iconography, they reflect subtle variations in purpose and provenance, one likely conceived for formal presentation, the other privately commissioned yet equally rich in symbolic meaning.

Together, they encapsulate the intersection of religious sentiment, national pride, and mechanical sophistication that defined Patek Philippe’s identity in the final decades of the 19th century.

A Watch for the Soul: Vacheron Constantin’s Passion-Inspired Timepieces

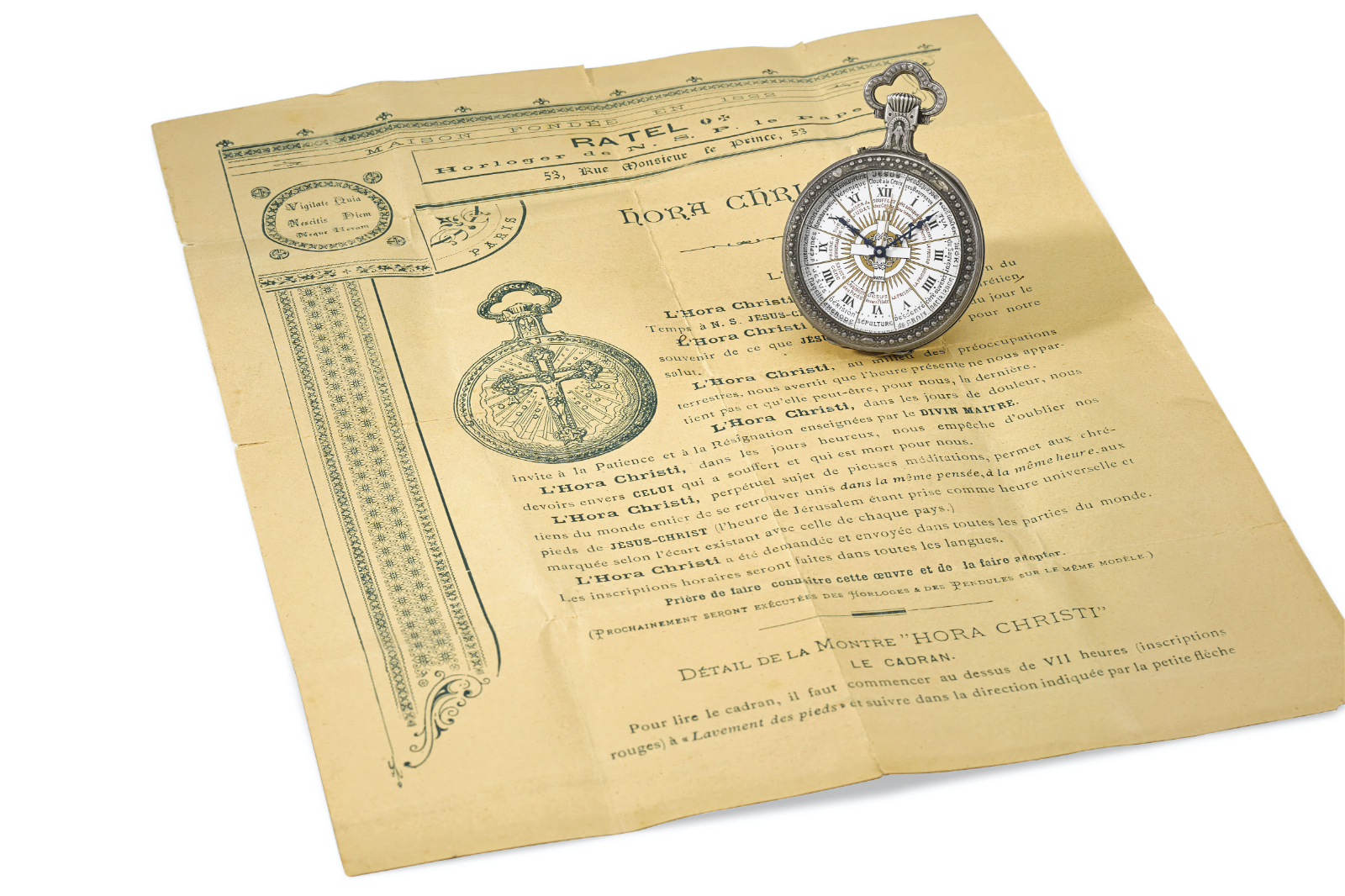

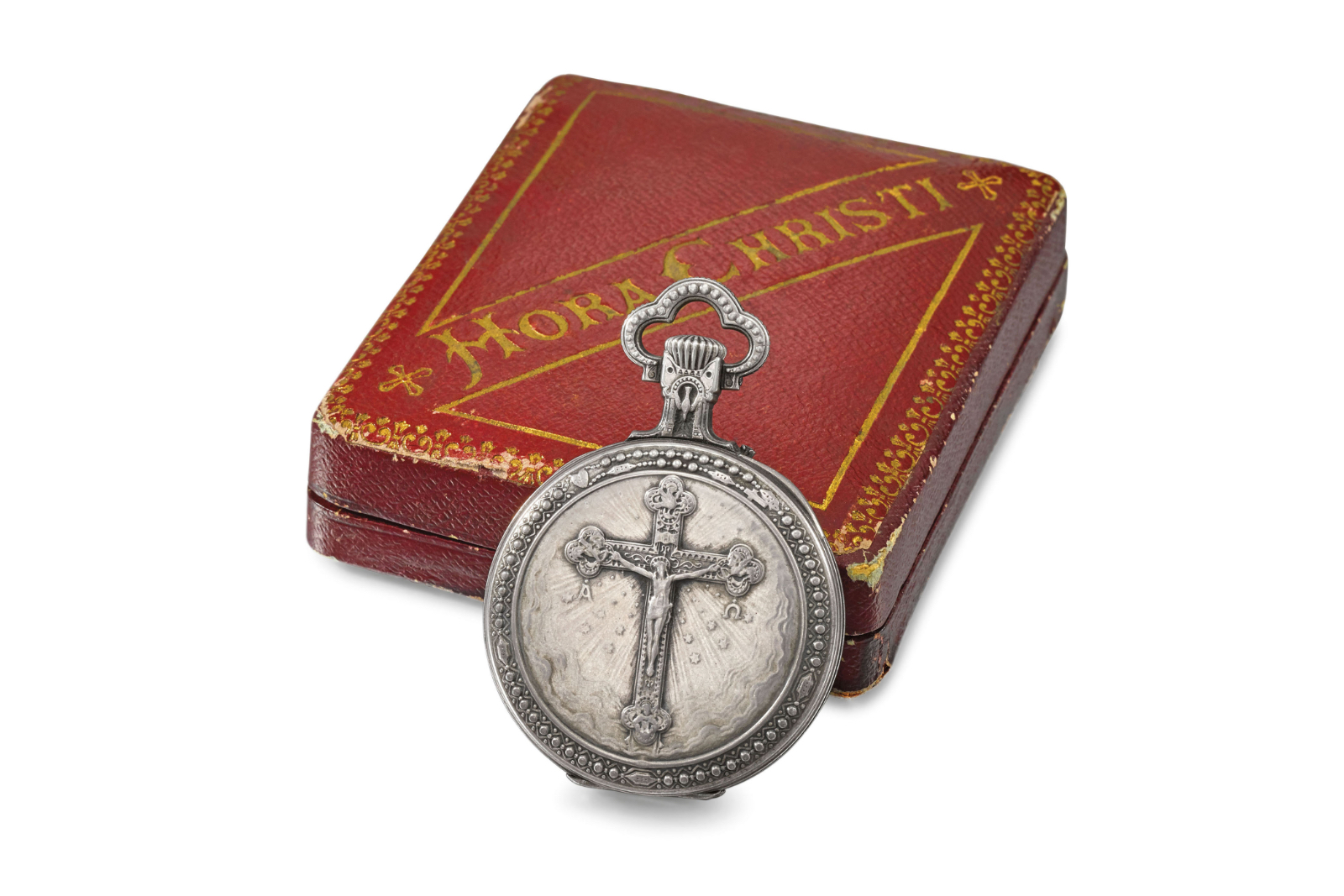

While several timekeepers have been associated with Pope Leo XIII, including ecclesiastical clocks and more conventional pocket watches, like the previous examples from Patek Philippe, none are quite like the Passion watches produced by Vacheron Constantin and Parisian retailer Ratel in the early 1890s.

Ratel and Vacheron Constantin gold case (1893). Image – Vacheron Constantin Museum

One particularly notable example, now preserved in the Vacheron Constantin Heritage Collection, is cased in yellow gold. This version was part of a small, spiritually focused series that transformed horology into a tool for devotion.

Ratel and Vacheron Constantin gold case (1893). Image – Vacheron Constantin Museum

The dial is divided into twelve radiant segments, each corresponding to a Station of the Cross. At the center sits a gilt sun surrounding the cross and crown of thorns, while the blued steel hands are shaped like the instruments of the Passion, such as the nails and the spear. A secondary gold hand points to the time in Jerusalem, encouraging reflection aligned with the Holy Land.

Ratel and Vacheron Constantin silver case (1893). Image – Christies

The hinged case back depicts a deeply symbolic crucifixion scene, encircled by a rosary in high relief. Inscribed along the band is the Gospel exhortation: “VIGILATE QUIA NESCITIS DIEM NEQUE HORAM”—“Watch therefore, for ye know neither the day nor the hour” (Matthew 25:13).

Ratel and Vacheron Constantin silver case (1893). Image – Christies

While several versions are known to exist—including examples in silver—this gold-cased edition stands out both for its craftsmanship and for its papal provenance. It remains a remarkable testament to the era when mechanical timekeeping could also serve as spiritual meditation.

The Watch from the Jura: Irénée Aubry and the Vatican’s Recognition

While the Patek Philippe tributes reflected the pinnacle of Geneva watchmaking, another gift revealed the ingenuity flourishing in Switzerland’s rural horological culture.

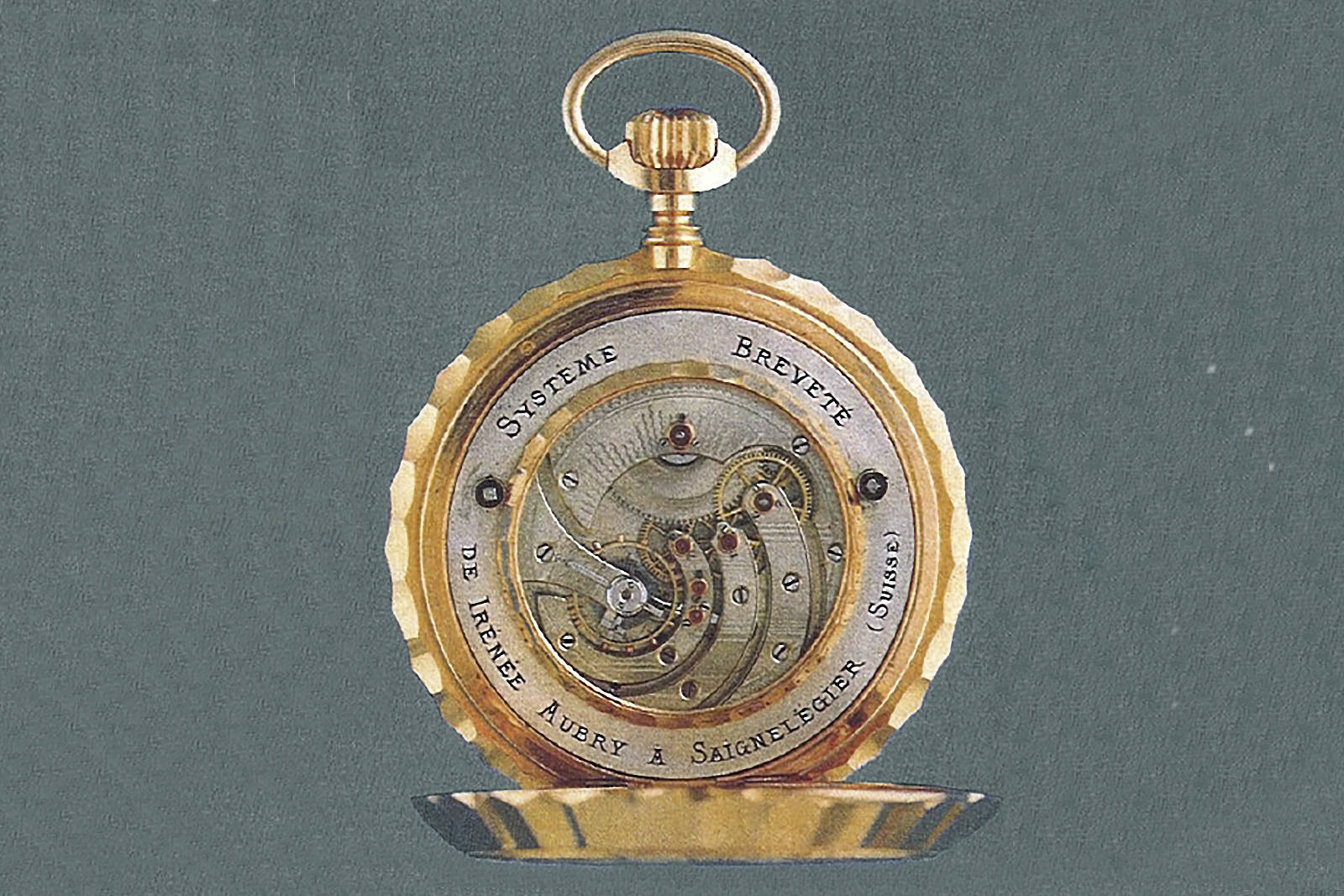

Commissioned by the canton of Jura in 1887, Irénée Aubry developed an exceptional pocket watch to be presented to Pope Leo XIII on the occasion of his Jubilee by a delegation of pilgrims from the Franches-Montagnes, the region where Aubry was born. This watch, known as the Montre du Pape (the Pope’s watch), ran for forty days on a single winding, an unprecedented achievement at the time.

Irénée Aubry “Montre du Pape” (1887). Image – Haute-Rive

The gold case of the Montre du Pape features a portrait of Pope Leo XIII and an engraving of the Franches-Montagnes coat of arms. Its fluted gold bezel, a refined decorative detail, would later echo in Stéphane von Gunten’s Honoris I, with a 1,000-hour power reserve that draws a direct line of inspiration from Aubry’s mechanical ambition.

Aubry’s innovation extended far beyond this singular creation. On 10 January 1889, he secured Swiss patent no. 88 for a mechanism capable of running for eight days without rewinding.

His invention was acquired by Graizely Frères, who registered the famous brand name Hebdomas. With further refinements, including a visible regulating organ, Hebdomas pocket watches became a commercial and cultural success, manufactured in La Chaux-de-Fonds and recognised at World’s Fairs well into the 1930s. The firm eventually evolved into Schild & Cie, but the origin of its breakthrough traces directly to Aubry’s Jubilee contribution.

Irénée Aubry “Montre du Pape” (1887). Image – Haute-Rive

His accomplishment did not go unnoticed by the Vatican. In 1888, Pope Leo XIII established the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice medal to honour laypersons who had rendered distinguished service to the Church during the Jubilee. On 8 December 1888, Aubry received the award, accompanied by a personal letter from Cardinal Rampolla, the Vatican Secretary of State. The diploma commended him for his “distinguished contribution to the universal demonstration with which the sacerdotal Jubilee of His Holiness was celebrated.”

The medal, a gold or silver cross suspended from a ribbon of papal colours, served as both a mark of recognition and a reflection of the Church’s growing appreciation for technical innovation as an expression of spiritual and cultural devotion. Aubry’s decoration, preserved by his descendants, was housed in a diplomatic presentation box.

While the Patek Philippe watch spoke to the aesthetic and mechanical finesse of a grand maison, Aubry’s creation embodied the spirit of local ingenuity and independent excellence. One was the product of Geneva’s elite ateliers; the other, a singular act of mechanical creativity from the Jura. They remain complementary narratives, one of brand prestige, the other of inventive zeal, both testaments to the way horology could serve as a bridge between craftsmanship and ecclesiastical ceremony.

Adding a further dimension to this tapestry, the devotional timepieces produced by Vacheron Constantin and Parisian retailer Ratel in the early 1890s exemplify the fusion of horological artistry and spiritual symbolism. These watches, rich in iconography and craftsmanship, underscore the deep connections between watchmakers and the papacy, reflecting a period when mechanical timekeeping also served as a medium for spiritual meditation.

Addition May 28, 2025: Papal watch made by Ratel and Vacheron Constantin in 1893 included in text.

Back to top.