Insight: Governors of Minute Repeaters, Sonneries, and Other Striking Watches

An essential mechanism regulating pace.

Repeaters are one of the most complicated mechanisms in watches and over the years the complication has been refined by successive generations of watchmakers. Now, perhaps more than ever, watchmakers dedicate absolute attention to perfecting the quality, speed, accuracy, and durability of the striking works.

Various components are required to chime the tunes of time with hammers and gongs. Paradoxically, amongst the most crucial parts of a chiming watch are those that work quietly, or silently, in the background – the governor.

One of the most recent new repeater calibres, the A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange Minute Repeater

What is a governor?

The governor regulates the speed of the striking pattern, in other words the pace of the individual chimes. A repeater movement contains a separate gear train for the repeating works, which are powered by their own smaller, auxiliary spring. The last component of this train consists of the governor.

The governor’s task is to introduce resistance in the repeater train, allowing it to be regulated. Therefore, less resistance accelerates the striking speed, while more resistance slows down the repeater chimes.

The Vacheron Constantin cal. 1731 with the secondary spring visible between the hammers

The fine-tuning of the repeater’s speed is prized as an essential factor in ensuring a perfect series of chimes. If the pace is too fast, the vibrations of the gongs produce jarring overtones that cancel each other out. If too slow, not only is the tune out of tempo, but the increased resistance can also potentially affect the repeater train and power reserve of the striking mechanism.

Achieving the ideal speed is solely based on human intuition and judgement. In this case, constructors and watchmakers at watch brands each have their own set of guidelines and procedures for cultivating the right sound that resonates with their brand – no pun intended.

Before governors

In antique repeating pocket watches of the early 19th century or before, it is common to find a different type of speed controller. Though these rely on the same concept of a repeater train, instead of a governor, the last pinion of the train is adjustable.

A Breguet grande sonnerie pocket watch from 1808 with adjustable pinions. Image – Sotheby’s

The pinion turns in a bushing that is attached to an eccentric post. By manipulating the pinion, the meshing of the gears can be varied. The deeper the depth, the slower the gears turn, and vice versa. The rotational speed of the train in turn determines the speed of the striking mechanism. Historically, watchmakers could adjust the speed of repeater chimes according to the owner’s preference.

The following Breguet grande sonnerie pocket watch is equipped with a pair of adjustable pinions for the chiming functions. Each pinion is adjusted with a rotating pointer against a scale engraved “V” and “L”, indicating the direction to speed up or slow down the chimes. Notably, this movement is based on a Swiss-made ebauche from the Vallee de Joux, despite being a Breguet timepiece made in Paris.

The adjustable pinions are circled in red. Image – Sotheby’s

The repeater regulator soon evolved beyond the adjustable pinion to be replaced by the far superior governor, which primarily falls into two categories: anchor governors and centrifugal governors.

The anchor governor

The anchor governor, also known as recoil anchor governor, was found in the earliest repeating pocket watches of the late 17th century. Operating on similar principles to a lever escapement, it took inspiration from the regulating mechanism in repeating clocks. With this system, the striking mechanism could be regulated to the desired speed.

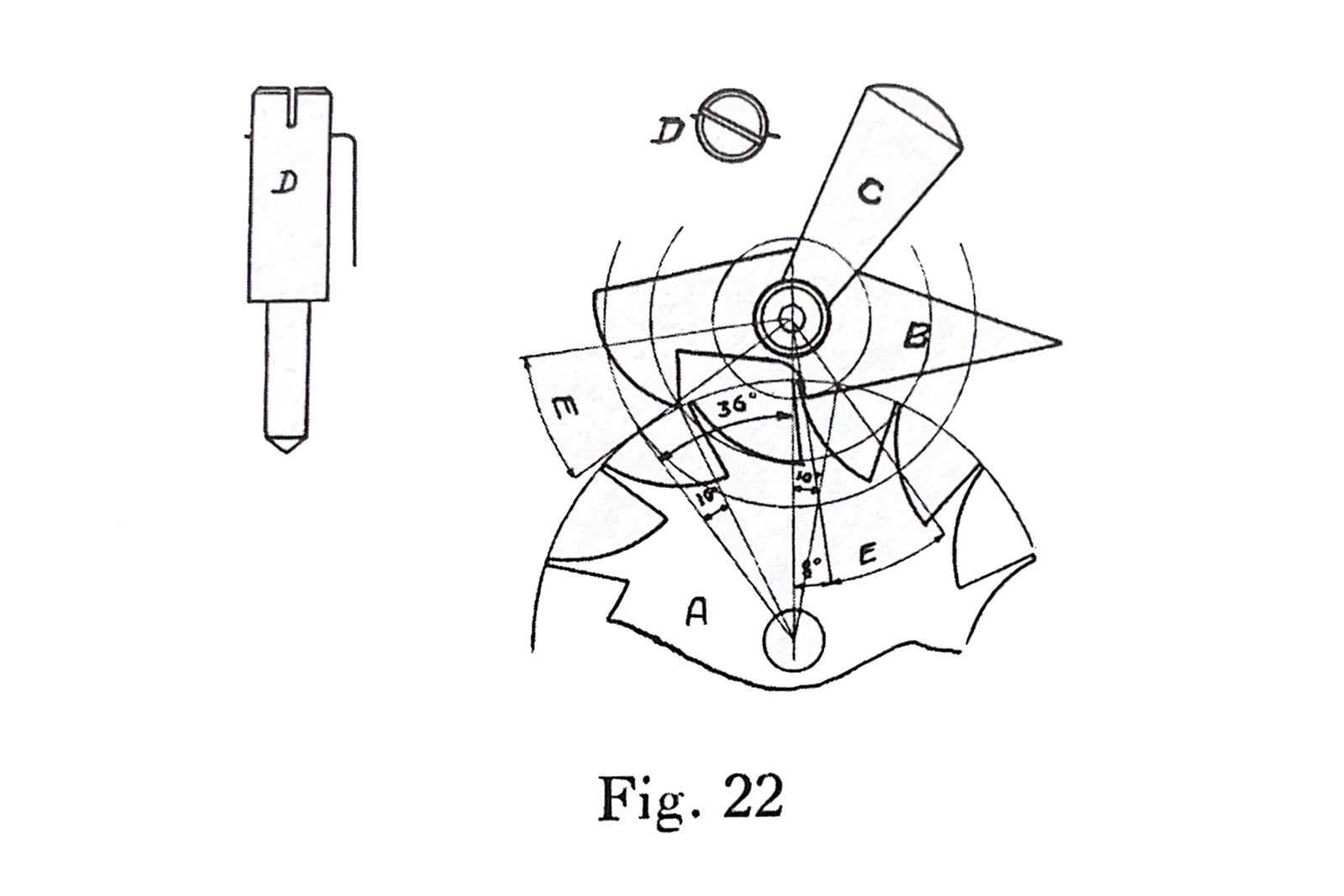

The end of the striking train consists of a ratchet wheel and a small recoiling click resembling an anchor. A fly is attached to the click staff, acting as a counterweight. Lastly, a regulating key with a screw head is friction fitted into the movement, along with a pin that is attached parallel to the key. The regulating key can determine the run of the fly; the wider the arc given, the slower the train runs. Conversely, the same principle applies.

An anchor governor. Image – Fig.22, plate 19 “A Guide to Complicated Watches” by François LeCoultre

Over time, the design of the anchor governor evolved as more precise engineering and materials became available. However, the fundamental concept of the system remained unchanged – it relies on mechanical friction to function.

That creates the most identifiable feature of the anchor governor, the buzzing sound produced by the lever as the repeater chimes. It can be argued the buzzing sound is a trademark of the repeater’s evolution and history, although most enthusiasts dislike the sound as it detracts from chimes.

For watchmakers, the buzzing sound is often considered an inconvenience while working, as it interferes with the fine-tuning of the repeater. Unsurprisingly, watchmakers long pursued a quieter governor.

The Breguet Classique 7637 cal. 567.2 that is based on a Lemania calibre modelled on 19th century repeating movements, hence the anchor governor

Centrifugal governor

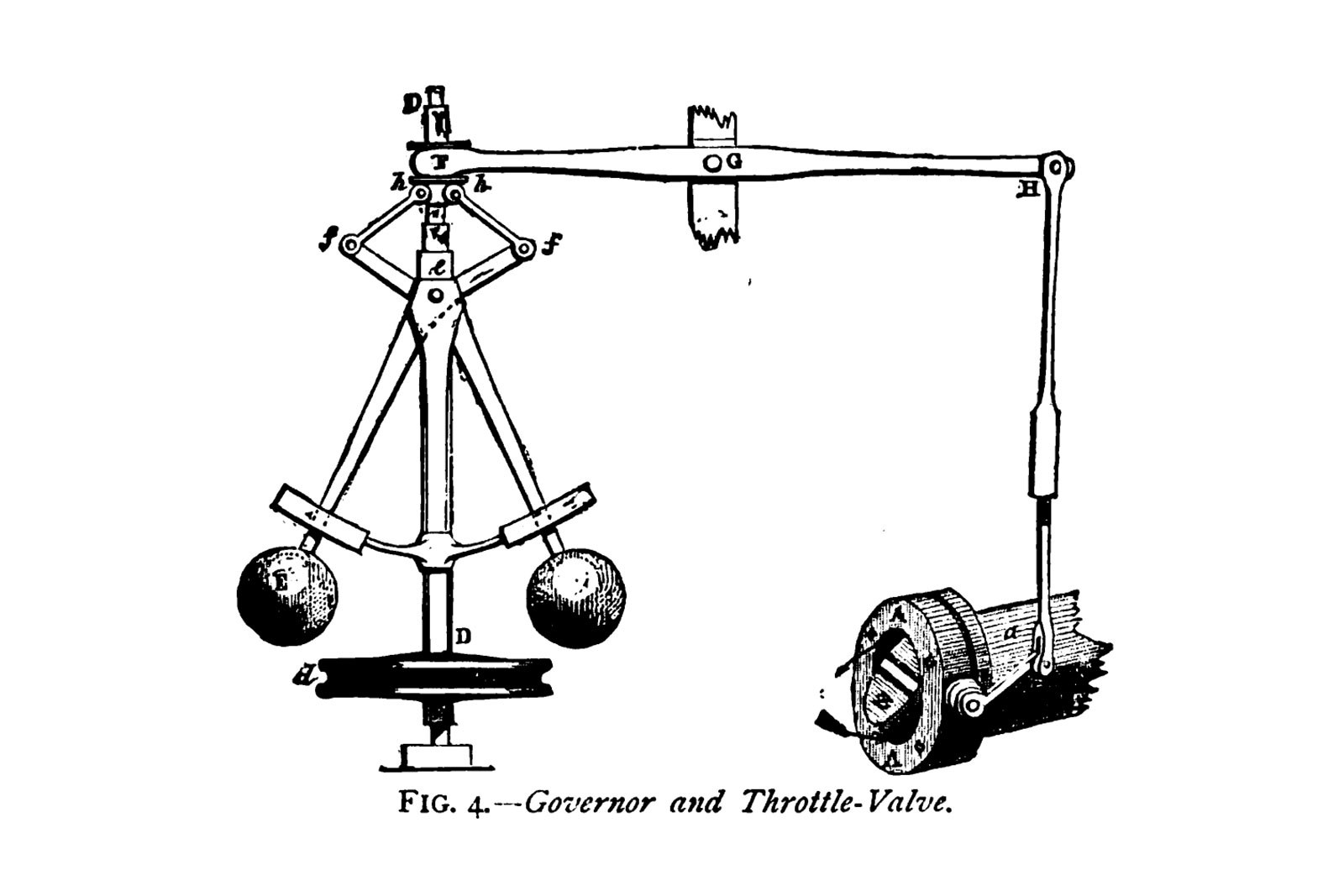

In the search for the perfect chime, centrifugal governors became the substitute for the anchor recoil governor. The concept came from Christiaan Huygens, the inventor of the pendulum clock, who created the centrifugal governor in the mid 17th century. He employed the invention to regulate the distance and pressure between millstones in windmills. Later in the 1780s, his concept was further developed by English engineer James Watt into a regulator for his steam engine.

A “fly ball” centrifugal governor. Image – “Discoveries & Inventions of the Nineteenth Century” by R. Routledge, 13th edition, 1900

Invented by Charles-Ami Barbezat-Baillot, founder of Le Phare, in the late 1880s, the centrifugal governor in watches operated comparatively silently compared to its predecessor. However, the centrifugal governors took a long time to make it into repeating wristwatches. That happened only in 1989 when Patek Philippe introduced its first serially produced minute repeating wristwatches, the refs. 3979 and 3974.

Operating on the principle of air friction, the centrifugal governor mechanism consists of an arm carrying two weights, fitted on the last pinion of the repeater train. Two flexible springs keep the weights close to the centre of the pinion. As the repeater chimes, the centrifugal force drives the weights outwards, similar to a figure skater spreading his or her arms.

Friction is then created when the connecting point of the arm and weights touches the inner wall of the mechanism. This friction slows the rotatory movement, causing the weights to return to the centre. The dancing weights, driven by the friction and centrifugal force, serves as a speed regulator for the striking works.

The centrifugal governor in the Patek Philippe Grande Sonnerie ref. 6301P-001

I am particularly intrigued by the recent innovations that expand the capabilities of centrifugal governors. For instance, in 2010 Breguet debuted the 7800 “La Musicale” that uses magnetism to replace friction, eliminating the governor scraping along the inner wall, making it a truly frictionless governor. Such advancements not only extend the lifespan of repeaters but also offer benefits beyond aesthetics.

The evolution of repeaters has flourished in contemporary watchmaking, driven by enthusiasts’ appreciation and demand for the complication, which will continue to push the limits of the industry.

The author is a watchmaker in Switzerland, working at an established brand.

Back to top.