Allure and Architecture – Patek Philippe Dome Clocks

The captivating story of timepieces and artisans.

A fixture in the Patek Philippe catalogue in the second half of the 20th century, the Dome Clock can nonetheless be considered a rather odd creation when juxtaposed against the main product lineup. Still today, the company seems rather keen on prolonging and even strengthening a product range that, otherwise, should have gone extinct decades ago.

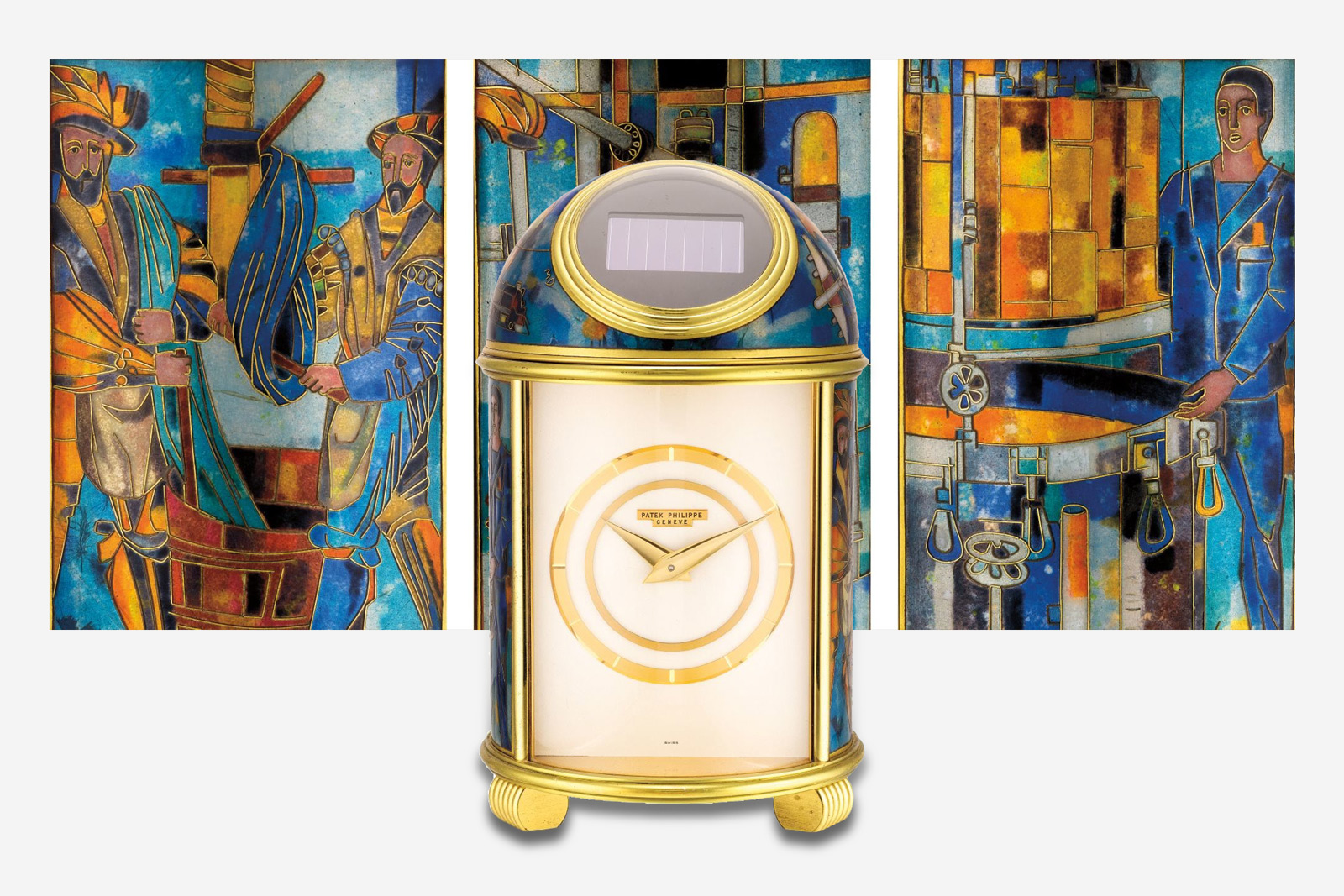

A few years after being introduced, Dome Clocks – formally known as Pendulette Dôme – began to appear as unique pieces with an unreasonable amount of exceptional artistic handwork mainly based on cloisonné enamel. And even though the timekeeping mechanism housed inside evolved over the years, it also became secondary, while its unusual and particular shape remained a unique artistic canvas becoming inextricably intertwined with Patek Philippe itself.

The influence of accuracy, precision and Observatory Competitions

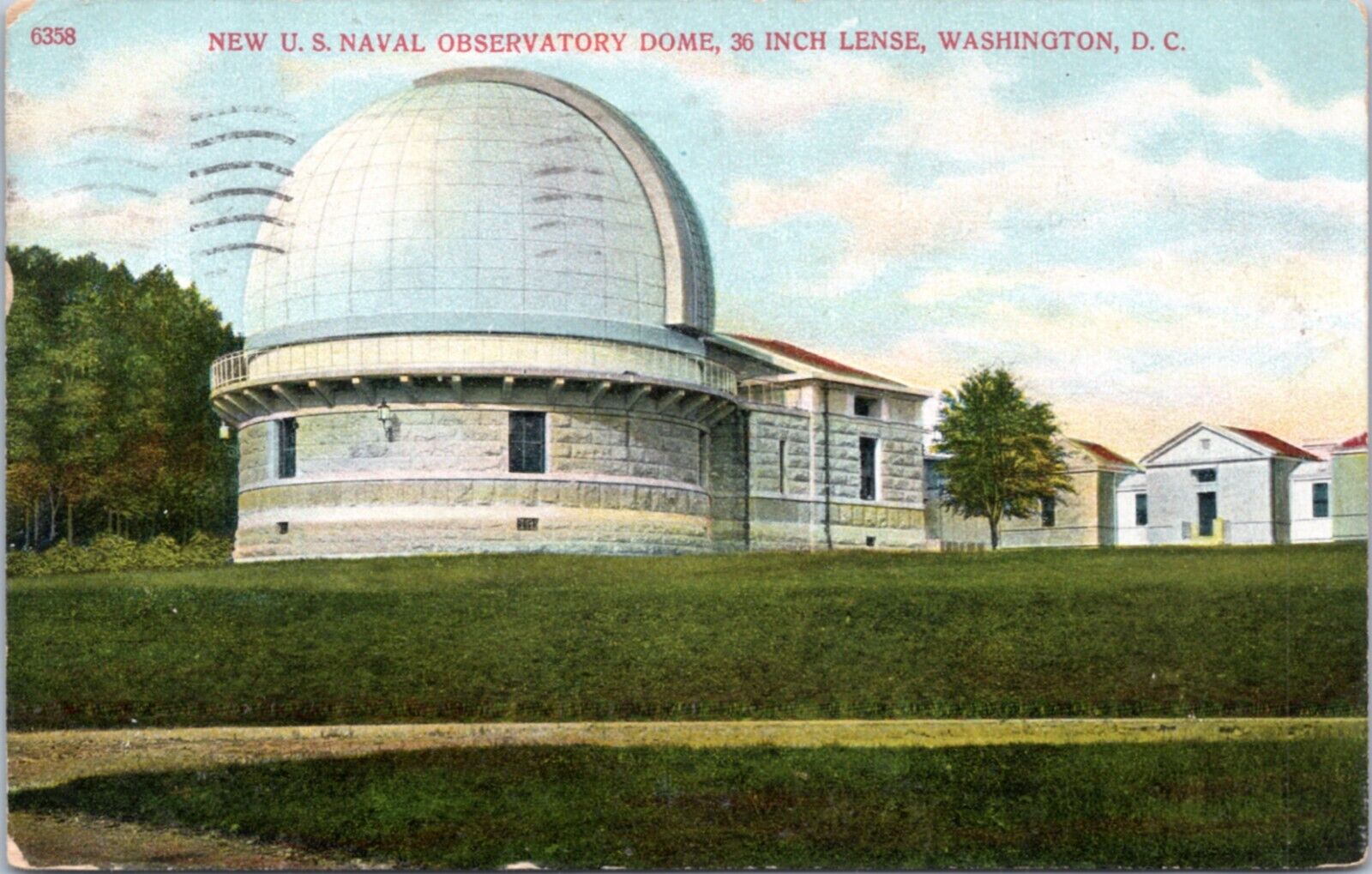

Following the period where prestige was measured by the number of medals and prizes handed out during the historic World Fairs of London, Paris or New York, the growing accuracy and precision of timekeepers required different metrics. One that could only be conceded by Astronomic Observatories during demanding chronometric competitions.

The prominent dome at the United States National Observatory in Washington D.C. Image –Wikimedia Commons

From 1879 onwards, chronometric contests at the Astronomical Observatory of Geneva became an institution in how watchmakers promoted the overall quality of the watches they produced. In 1884, Geneva was joined by Kew and Teddington in Great Britain and, in 1885, by Besançon in France. These contests started to draw interest from watchmakers, which had become increasingly thirsty for public recognition of accurate timekeeping in the modern age.

An advert put out by Gondolo & Labouriau advertising the results from the Geneva Observatory competition for 1915-16.

When finally the Geneva Observatory tests ceased entirely in 1968 due to the arrival of quartz watches, precision and accuracy had already become associated with astronomical observatories in general, symbolised by their domed shaped cupolas rising high above their roofs. Observatory Domes had created a generation-wide public perception of scientific rigour, exactitude, and meticulousness. The association between observatories and their domed architecture contributed to the romanticised image of astronomers and scientists studying the universe with meticulous attention to detail and unwavering dedication. The cultural significance of the shape of a dome now extended beyond its functional aspects. It became a recognisable symbol of scientific pursuit and human curiosity about the cosmos.

Henri and Philippe Stern and the photo-electric cell

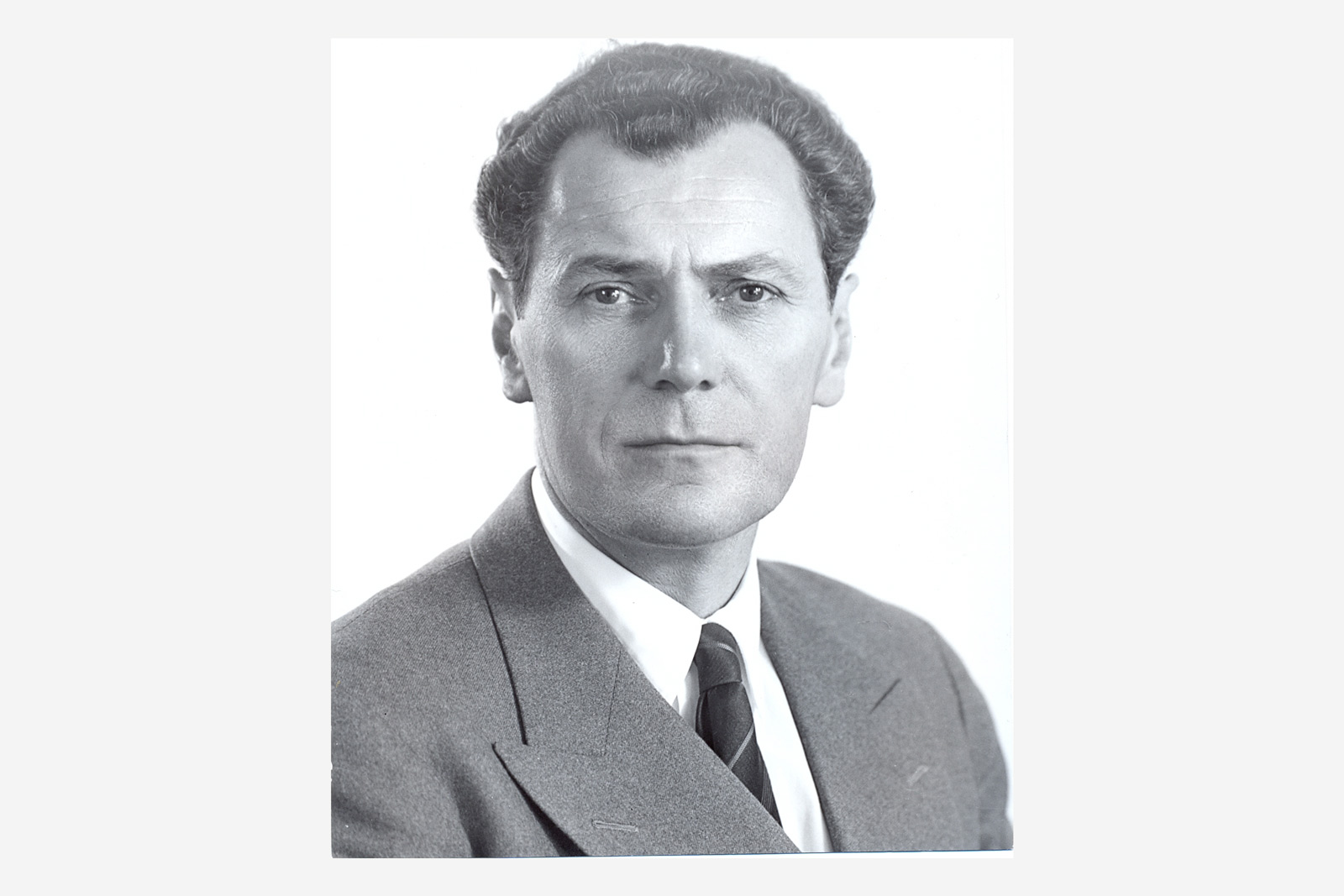

When the first Patek Philippe Dome Clocks appeared around 1958, the company’s presidency was in the hands of Henri Stern, the grandfather of the current president, Thierry. Young Henri Stern studied at the École des Arts et Métiers, where he consolidated a sound knowledge of the arts, followed by an internship with a steel engraving specialist. An education that turned Henri into a talented draughtsman and engraver with an impeccable aesthetic sense at the service of “Stern Cadrans”, a few years before starting his work at Patek Philippe.

Henri Stern. Image – Patek Philippe

During the 1940s and early 1950s, Henri Stern witnessed a vogue for cloisonné enamel dials, while at the same time, Patek Philippe entered the world of electronic timekeeping. In 1948 the maker started its Electronics Division, followed in 1954 by the creation of its first photo-electric desk clock. Patek Philippe had invented a new method of powering a timepiece.

Housing the pocket-sized manual calibre 17’’’250 E, a small rotatable solar panel on the top of the dome supplied energy to a storage device within, transmitting energy to power the mechanical movement. Thanks to a photo-electric cell, the timepiece was powered by a movement wound automatically by illumination, with a daily light exposure for 4 hours at 200 lux sufficient to keep the clock running indefinitely.

Tiffany & Co., of course, had the privilege of selling the first examples as of 1957, the year Henri Stern returned to Geneva to finally replace Jean Pfister as President and General Director of Patek Philippe.

Image – Patek Philippe

Series-produced Dome Clocks started appearing in retailers’ windows around 1957, with their guilt cases hand-engraved with an argyle lozenge pattern (ref. 701). Rarer variations of this period also showed guilt brass elements applied over leather (ref. 709 and 725 for ex.).

By the 1970s, Patek Philippe had started using battery-powered quartz technology in its clock production and began phasing out solar versions, which completely disappeared by 2007.

In 1962, Philippe Stern joined the family business eventually becoming Managing Director of Patek Philippe in 1977, setting out a strategy of reinstating specific Metier d’Art crafts closely associated with the traditions of the city of Geneva.

By the time he took up the presidency of the company in 1993, Patek Philippe was single-handedly supporting the craft of miniature painting, cloisonné enamel and their respective dwindling number of artisans.

In an interview for Europa Star in 2019, Philippe Stern explained the history:

“… for a heritage to remain alive and be passed on as a legacy, it must be maintained. …Our Dome table clocks, which reflect our mastery of the rarest artistic crafts, are a great example of this. Around 1965 we had a hundred of them or so in stock. No one was buying them any more, but we continued to make them. What we wanted, above all, was to preserve the expertise required to produce them. At the time, there was hardly anyone doing enamelling. We continued to give our enamelers work so their “secrets” would not be lost in the mists of time.”

So the emphasis for the existence of Dome Clocks fell on the craftsman, the artisan.

The fascinating art of cloisonné enamel

Of all the decorative techniques, the art of enamelling is undoubtedly the most challenging to master. The risk of failure is exceptionally high. Any mistake, however minuscule, could compromise a work which, in the case of Dome Clocks, could take up to a whole year to complete.

A ref. 1415 with a cloisonne dial.

The technique of cloisonné involves curving fine gold wires to define the contours of the chosen design. These wires are then soldered onto the surface of a plate or dial, and the areas within are subsequently infused with powdered enamel, undergoing multiple rounds of firing.

Applying enamel onto the curved panels and dome demands advanced technical prowess. The reason why only a few unique examples of these masterpieces emerge from the workshops of Patek Philippe each year.

Artist Enamelers

Whenever signed, the work performed on Dome Clocks is a testament to the individual artisans’ contributions to these remarkable timepieces.

Madame Michel Deville (1924-2003)

Madame Michel Deville (1924-2003) transformed the artistry of Dome Clocks with her masterful enamel work. Deville’s approach was notably distinctive, often imbuing classical subjects with a markedly 20th-century flair, enriched by the influences of Cubism and Surrealism. Her work, produced between 1959 and 1970, was occasionally signed M.D.

Image – Phillips

Madame Luce Chappaz

Madame Luce Chappaz’s legacy predominantly lies within her association with Patek Philippe. Her distinctive signature adorned over 50 pieces from the late 1950s to the early 1990s, including dome clocks, pocket watches, and miniatures. Her artistic journey culminated with the celebrated 1991 700th Swiss anniversary clock.

Image – Phillips

Madame Marie-Francoise Martin

The available information on Madame Marie-Francoise Martin is scarce. Besides her signature, MFM, we only know that her work was incredibly distinctive and unique, mainly denoted by her vibrant colours.

Image – Christie’s

Madame Elisabeth Perusset Lagger

As a master enameller, Madame Elisabeth Perusset Lagger demonstrated exceptional expertise in the intricate art of cloisonné work. Her distinctive signature, “EPL,” seems to adorn all of her creations.

Image – Christie’s

Madame Michèle Mauris

Madame Michèle Mauris started her career at Patek Philippe. Her signature consists of two “M” letters, usually placed in a panel corner of the Dome Clocks she executed.

Image – Phillips

Today, the best opportunity to see some of the latest and rare examples of Dome Clocks is through Patek Philippe Watch Art Grand Exhibitions, which, after being organised in Tokyo this year, will be held in Milan in 2025. Another opportunity arises with the Rare Handcrafts exhibition coinciding with the Watches & Wonders show, utilising the historic Patek Philippe Salons in Geneva as its venue.

Three of the Dome Clocks released at this year’s Tokyo Watch Art Grand Exhibition. Image – Patek Philippe

Back to top.