The Last Cabinotier of Saint Gervais

The horological curiosity in the historic centre of Geneva watchmaking.

Few tourists find themselves in Geneva’s historic Saint Gervais district, the city’s revolutionary hotbed where Jean-Jacques Rousseau spent his boyhood in the early 18th century, and from where James Fazy overthrew Geneva’s ruling oligarchy in the revolt of 1846. Throughout those times, Saint Gervais was above all the city’s horological powerhouse, a warren of sweatshops known as the Fabrique Genevoise, turning out the myriad parts and decorating the watches that made Geneva synonymous with luxury craftsmanship.

The workshops were presided over by those emblematic figures of Geneva watchmaking, the radical, opinionated yet urbane cabinotiers. “A Parisian watchmaker,” remarked Rousseau, “can only talk about watches. But you can take a Geneva watchmaker anywhere.”[1]

With the revival of luxury watchmaking in the late 20th century, the Fabrique was re-born in the less picturesque ZIPLO (Zone Industriel de Plan-les-Ouates) on the outskirts of town, and the sweatshops are now known as manufactures.

Yet there’s still one watchmaker left in the remnants of old Saint Gervais, upholding the cabinotier tradition in this historic centre of Geneva watchmaking.

Bruno Pesenti, the last watchmaker in Geneva’s historical watchmaking district, wears the smock and eyeshade of the cabinotiers who made watches here 200 years ago

Forgotten brands

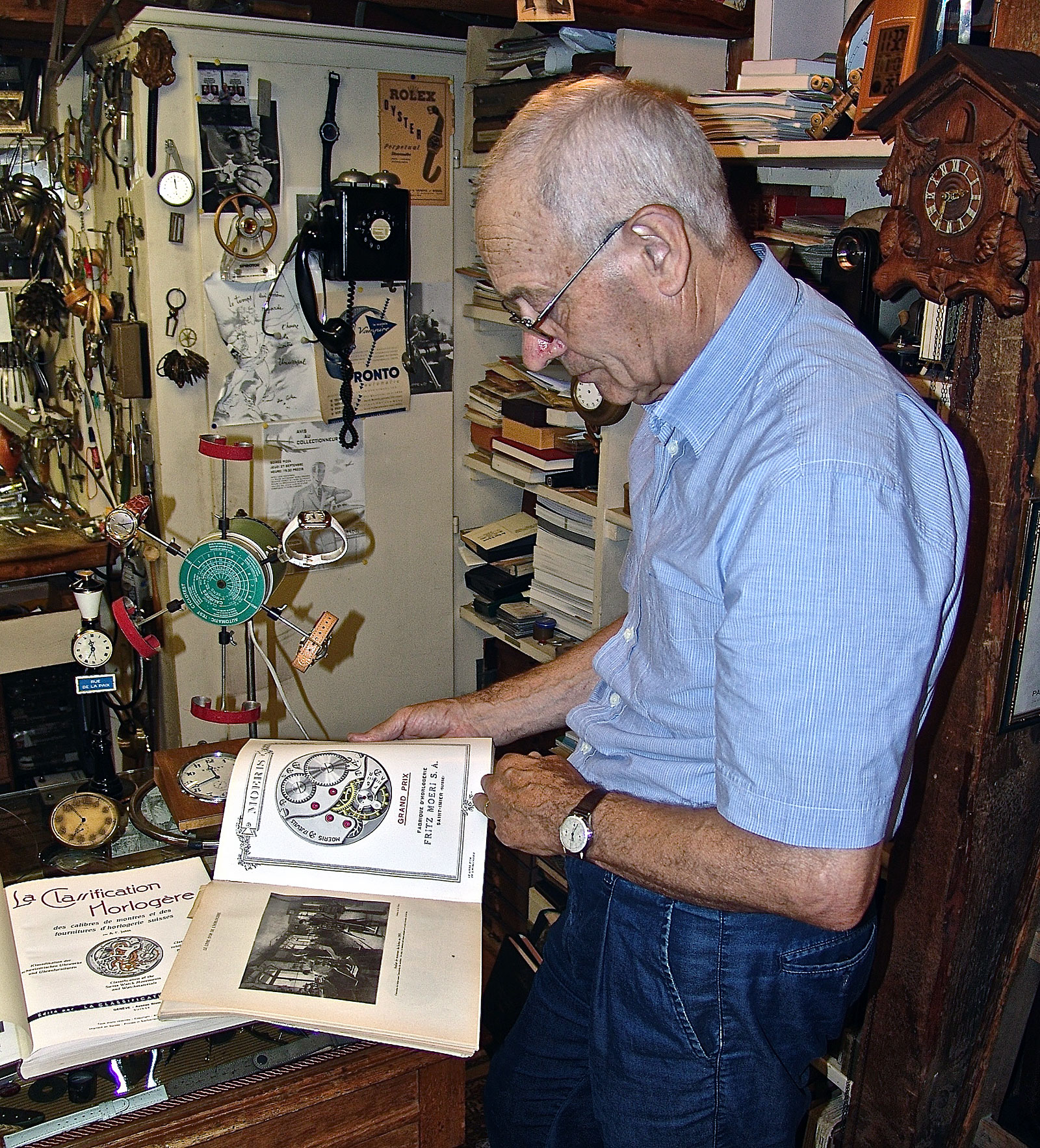

Bruno Pesenti is one of the few watchmakers who can still fix anything pre-quartz. He welcomes you with modest pride and old-fashioned Italian charm to the unique horological world he has created in his tiny curiosity shop, Au Vieux Saint Gervais, in the medieval Rue des Corps-Saints. It’s crammed with the accumulation of 40 years of watchmaking, a rich museum of the ordinary watch, as far removed from from the glitz of contemporary luxury watchmaking as you can get, and miles away from ZIPLO.

Pesenti specialises in bringing to life those watches proverbially found in the backs of drawers — forgotten brands like Angelus or Richard — for he, if anyone, has the parts. Fusee chains? Pesenti displays a selection. Enamel dials? He has drawers full — rectangular, round, Art Deco. He brings out boxes of winding crowns, rotors, movement blanks of every kind, an exquisite little Patek Philippe movement. If you bring in your grandfather’s wristwatch, he could fit it with an original 1940s strap, beautifully crafted and wonderfully supple. He still has them in their original packaging. And he’ll find the right buckle as well.

It’s easy to miss the modest Au Vieux Saint Gervais shop in the Rue des Corps-Saints

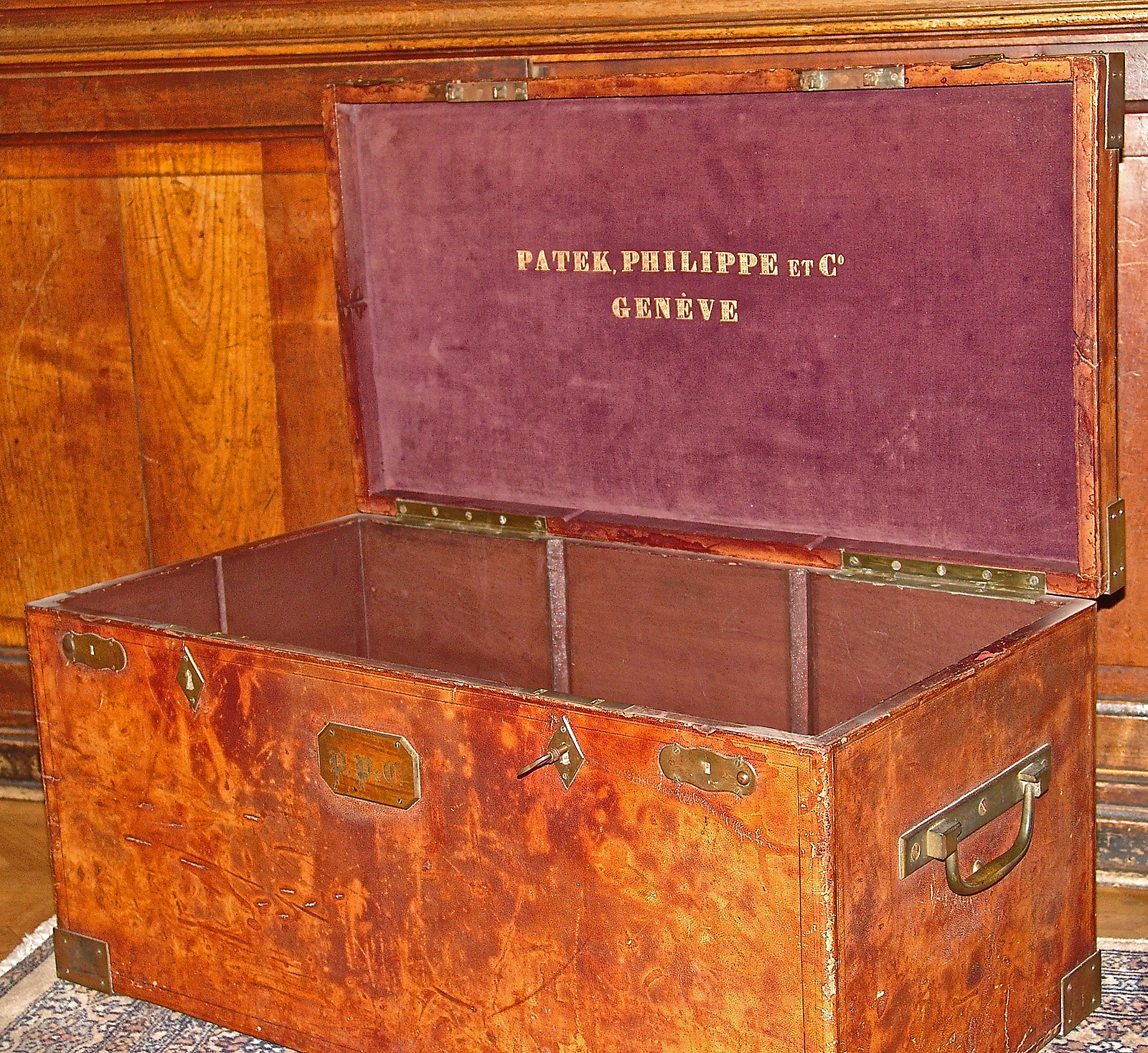

The walls are stacked two or three deep with clocks of every variety, old pictures of Saint Gervais, display cabinets of pocket-watches and watchmaking tools. You discover a massive brass dividing table, the slightly scorched Patek Philippe display trunk Norbert Patek took on his travels, a collection of old advertisements and watch-related postcards. Strings of wristwatches, buckled together, hang from shelves. A music box plays when he opens his cupboard door.

A ladder leads to a library in the loft piled with watch reference books, and the entire collection of early green Antiquorum catalogues – the first all-wristwatch auction catalogue of October 1981 lists a Patek Philippe ref. 2499 with a high estimate of CHF30,000. They fetch at least 15 times that today.

Bruno Pesenti attends to a customer in his horological curiosity shop

A window display to tempt the browser

One day such watches might become fashionable

This slightly scorched trunk might have accompanied Antoine Patek on his sales trips to the United States in the 1850s

Infernal machine

Pesenti delights in unusual horological applications. “Try to guess what this is.” He brings out a book-sized box made of thick metal plates. Some kind of industrial automaton? A luxury gadget in disguise? It turns out to be a mechanical time fuse to set off an explosive charge… or a bomb. Set a getaway time of up to 72 hours and a spring driven dynamo generates the electricity to detonate the charge.

For serious restoration, Pesenti has a fully-equipped mechanical workshop at his home in Genthod, next door to Franck Muller’s first workshop. Workbenches and cabinets stuffed with more components, gravers of every kind, dozens of tweezers, bow lathes, more clocks.

Everything to hand at a cluttered workbench

Pesenti spent much of his childhood on the shores of Lake Como helping out in the workshop of his uncle, the local watchmaker. Inevitably he started out by taking apart the family clocks. Although trained as a shop salesman, he found his vocation and a natural talent for horology in Geneva as a watchmaker in the restoration workshops of the Galérie Genevoise de l’Horlogerie Ancienne, the predecessor of Antiquorum, the auction house founded by fellow Italians, Osvaldo Patrizzi and the late Gabriel Tortella.

In those days, all watches were revised in the workshops before they went on sale. In 1978 he set himself up as an independent watch restorer and dealer in his current premises in Saint Gervais. By then, just about every kind of watch had passed through his hands.

From his collection of movements, dials and cases…

Bruno Pesenti can make up a customised watch

The end of the independent watch repairer

Watchmakers like Bruno Pesenti, who are as familiar with the adjustment of a 19th-century pocket chronometer as with the restoration of a rare centre-second Morbier clock, are rare treasures today. The brands, having vertically integrated their upstream suppliers and downstream distributors, have now extended their control to the after-sales service.

Independent watchmakers have been starved of parts and gradually smothered. Watch repairers of today are obliged to specialise in the products of one or other of the big brands, and consumers have little choice but to accept the unasked-for replacement of parts and the swingeing costs of not actually owning your watch but looking after it for the next generation.

Contemporary watches with proprietary movements are now excluded from Pesenti’s care — his intervention might invalidate the guarantee, even if he were supplied with the parts. But that does not prevent the same brands from asking him to prepare one of their vintage models for a six-figure sale at auction.

An extensive library enables Bruno Pesenti to identify most vintage watches

The last authentic watches

Au Vieux Saint Gervais is above all a museum of a forgotten horological world, a tribute to everyman’s watch. The unfashionably small wristwatches of defunct brands, and their predecessors, lumpy steel or silver pocket-watches were the utilitarian and necessary objects of the pre-quartz era. These are the last authentic watches, applying the latest horological technology of their time, in contrast to the reproduction of the same, now obsolete, technology in current models.

He’s used to working on ancient machines

Among all this bewildering stock gleam rare nuggets; you can find just about every type of selfwinding movement or watch from Harwood to micro-rotors, or a Rolex “Bubbleback” with a “California” dial. And to be perfectly accurate, you can pick up an electrically-impulsed observatory master clock of the 1930s or a fine 1980s Imhof radio-controlled table clock that will not deviate more than a second in millions of years.

Now in his seventieth year, Pesenti is wondering who will take over this life’s work when he hangs up his cabinotier’s smock. Are there any young watchmakers with the range of skills necessary to carry forward this horological heritage? If not, it would close a chapter in the history of watchmaking.

1. Daniel Palmieri and Irène Herrmann, Faubourg Saint-Gervais, mythes retrouvés (Slatkine, Geneva, 1995).

Back to top.