Auction Watch: Breguet Skeleton 30-Day, Constant Force Clock by Philippe René Jaccard

At Christie's New York.

One of the most intriguing timepieces being offered in the final run of watch auctions for 2019 is not a wristwatch, but an incredibly rare table clock made by Breguet in 1934 that’s going under the hammer at Christie’s.

It hardly looks like a typical Breguet – having no engine-turning or gilding or blued steel hands – but is remarkably striking, with a skeletonised, architectural movement that is modern-looking despite being 85 years old.

Abraham-Louis Breguet is rightly regarded as one of the most important watchmakers in history, whose inventions range from the natural escapement to the tourbillon, while being commercially savvy enough to become a leading watchmaker to the Ottoman Empire. But his descendants ventured into other businesses by the mid 19th century, most notably aviation, so the watchmaking operation was sold by Louis-Clément Breguet, grandson of Abraham-Louis, in 1870 to English watchmaker Edward Brown.

The Browns kept the workshop in Paris, though it moved several times over the decades. During the century that the Brown family ran Breguet – Brown’s grandson George sold the company to French jeweller Chaumet in 1969 – the firm mostly retained the signature Breguet style and produced a large variety of timepieces, but in tiny quantities, often relying on external specialists for movements and components.

Timepiece no. 3142

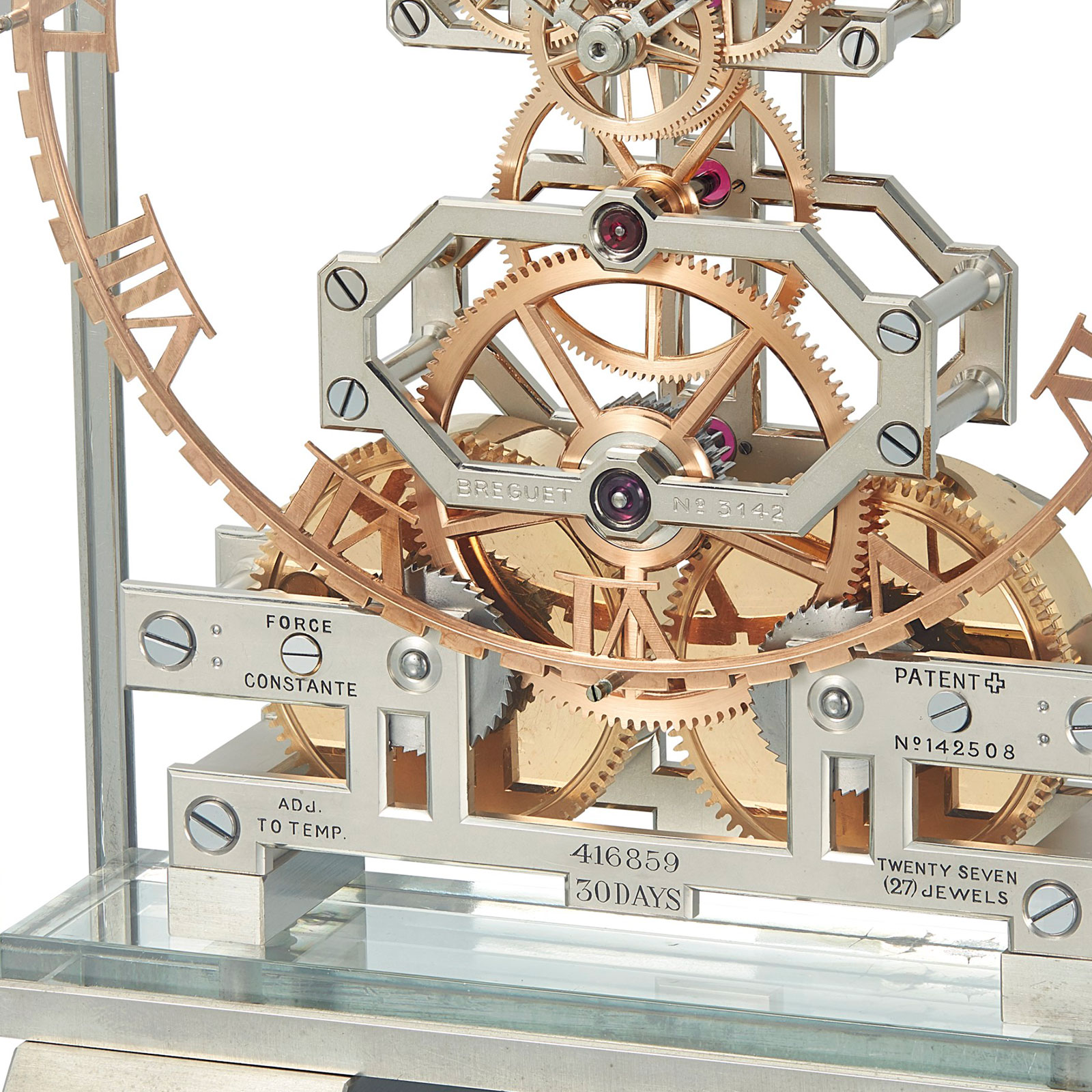

This clock is one such timepiece from the period. A unique piece according to the accompanying Breguet museum archive, it’s a smallish desk clock, standing about 7in or 18cm high, with a round-topped “humpback” shape. The clock bears the Breguet serial number 3142, as well as the movement number 416859.

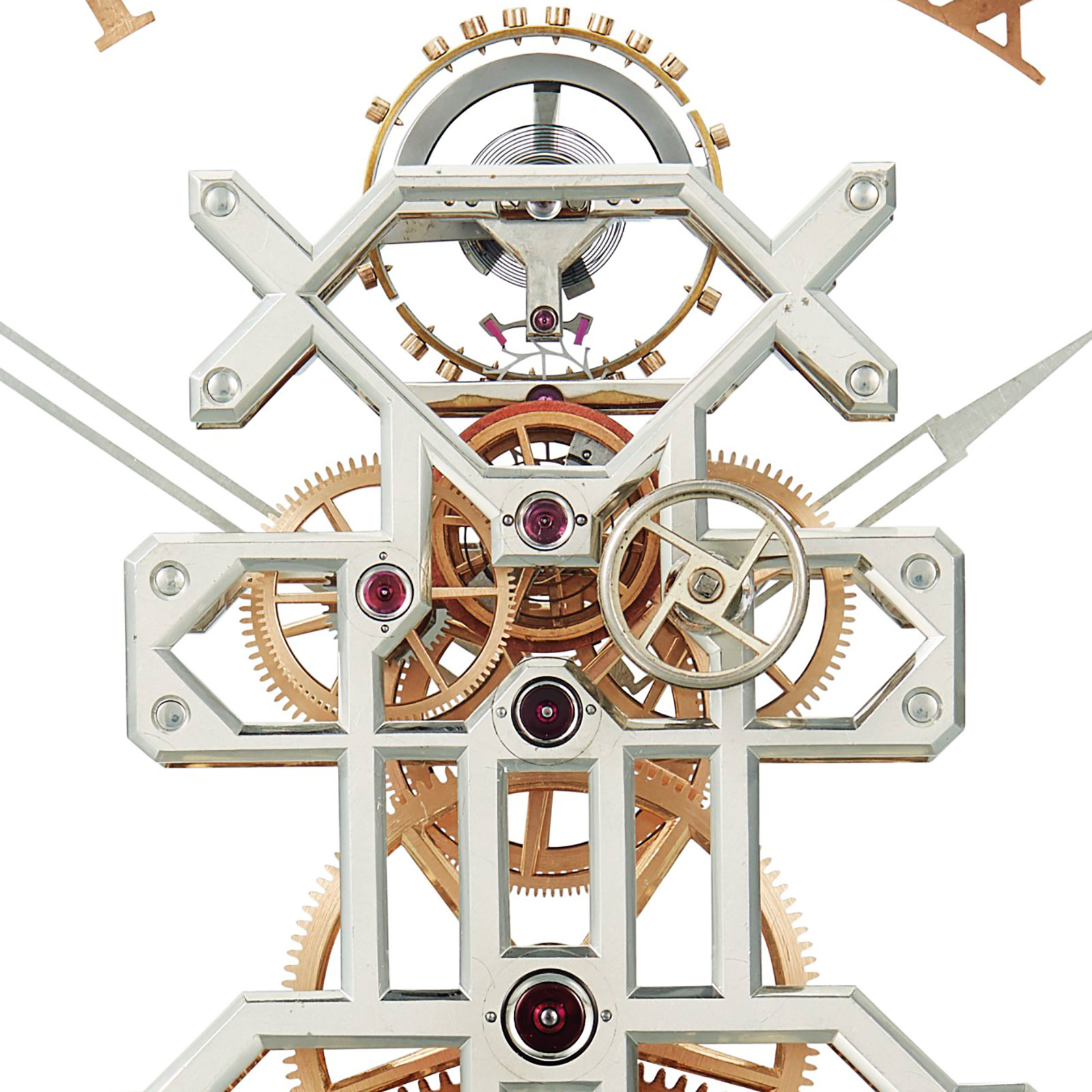

Though the silhouette of the clock is classical, its details are strikingly modern, with an geometric, symmetrical movement sitting inside a steel case panelled in glass.

The skeletonised frame of the movement is made of Platinix, an alloy of palladium, while time is indicated by two hands against an copper-alloy chapter ring with open-worked Roman numerals. And it has two large mainsprings, each wound via a swivelling key on the back of each barrel.

Though the clock is only signed Breguet, the Swiss patent number engraved on the base of the movement leads us to Philippe René Jaccard of Geneva.

Jaccard’s invention

Active in the early decades of the 20th century, Philippe René Jaccard was watchmaker-engineer whose premises were at 12, Rue du Port in Geneva. He invented complications and built movements for watch brands, much like the better-known Louis Cottier, who is most famous for having invented the world time mechanism that is today used by Patek Philippe and others.

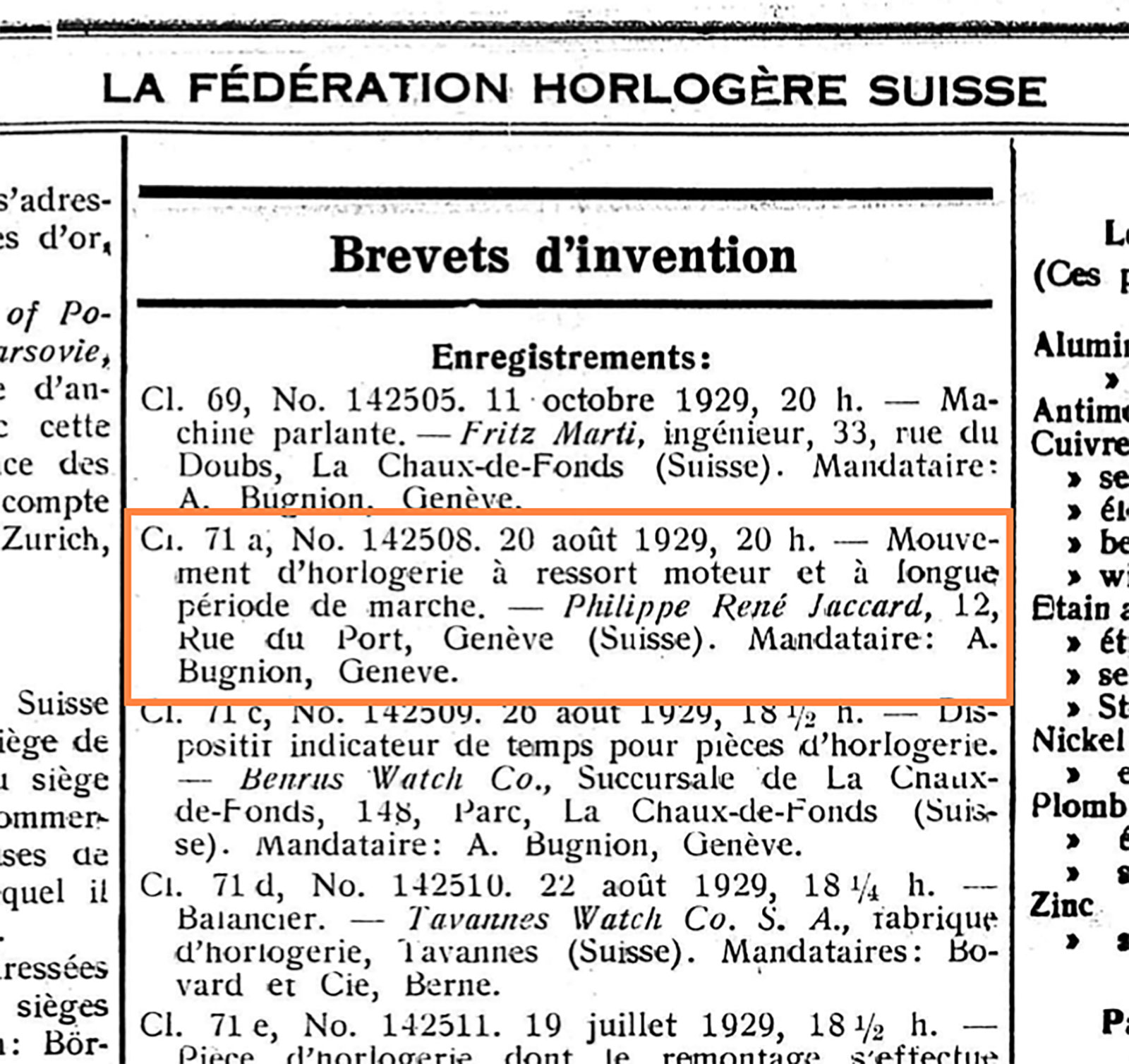

Amongst his inventions was a clock movement with a 30-day power reserve and constant force escapement, which he patented in 1929. The patent was announced in the October 1930 newsletter of industry body La Fédération Horlogère Suisse, a predecessor of today’s Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry (FH).

According to the notice, the patent was filed by Jaccard’s lawyers, A. Bugnion (a firm specialising in intellectual property that is still in operation today) at 8pm on August 20, 1929. Jaccard was then granted Swiss patent 142508 for a “horological mechanism with a mainspring of extended operation”.

Jaccard’s invention was a symmetrical, A-shaped clock movement with two large barrels at the bottom providing a 30-day power reserve. But the torque from the mainsprings over the 30 days presumably varied significantly at the start and end of the period, hence the need for a constant force mechanism.

Integrated into the escapement was a remontoir d’egalite, a small spring that is wound up at a constant interval by the going train, providing a fixed amount of energy to the escapement as it unwinds and ensuring stable timekeeping over 30 days.

The remontoir spring is visible just below the escape wheel and pallet fork

Jaccard supplied the movement to a handful of brands, likely in extremely tiny numbers as such clocks hardly ever emerge. The known example to be sold publicly was a Vacheron Constantin clock from 1933 that achieved 242,500 Swiss francs at Antiquorum in 2002. With that clock as an inspiration, Vacheron Constantin unveiled the Arca clock, powered by a modern replica of the original movement, for its 260th anniversary in 2015.

Mr Solvay’s big purchase

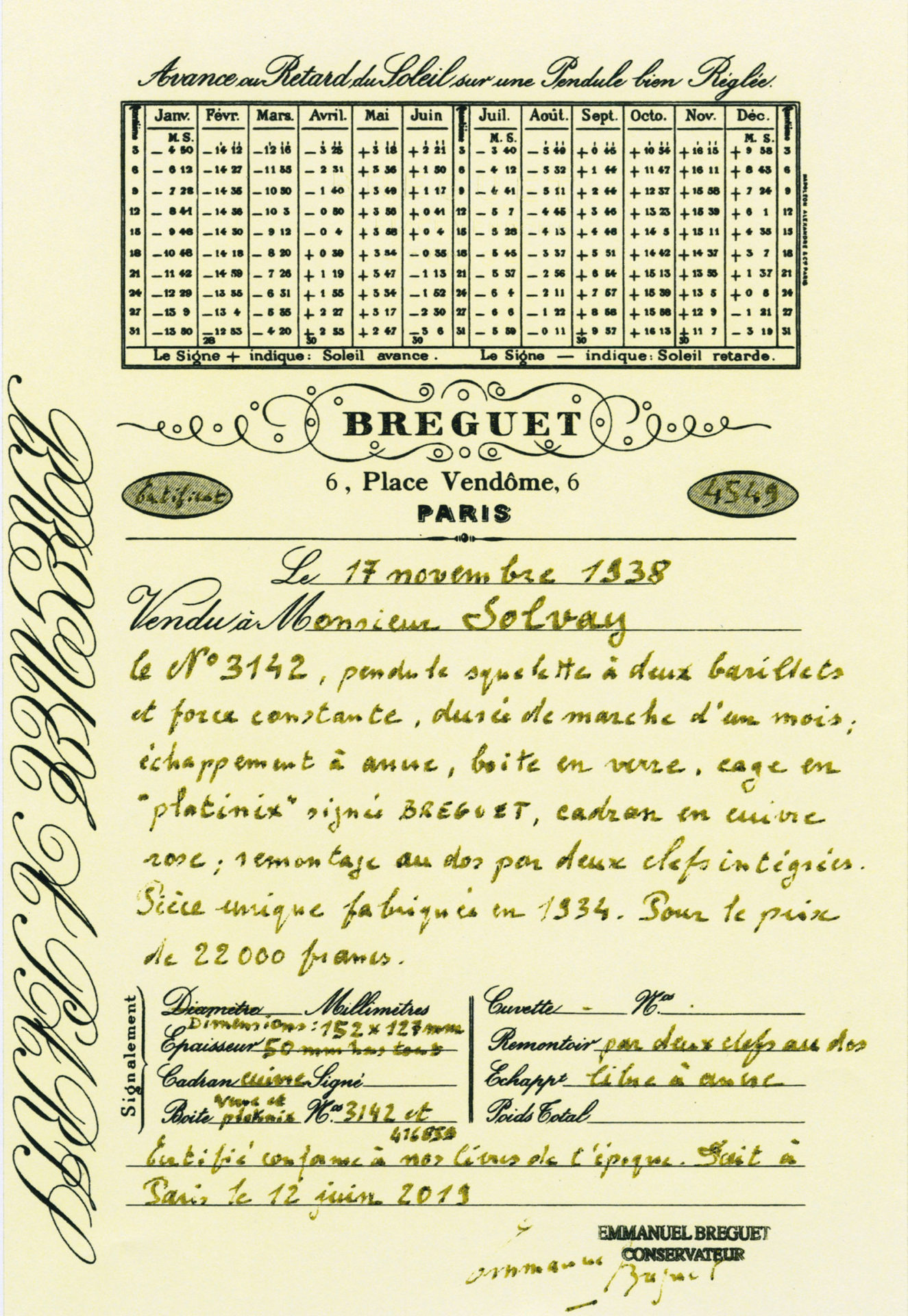

Beyond its unusual movement and rarity, this Breguet clock is also notable for having been sold to a Mr Solvay in 1938, according to the Breguet archive extract that accompanies the clock.

According to Christie’s, the buyer was probably Ernest-John Solvay, grandson of noted Belgian chemist and entrepreneur Ernest Solvay. The family is perhaps best known for having founded the Solvay Conference, a symposium on chemistry and physics that takes place every three years or so.

The Breguet archive extract

But even more significant is how much Solvay paid for the clock: a whopping 22,000 francs, more than many highly complicated pocket- and wristwatches of the period.

In 1934, for instance, Breguet sold a one-off, white-gold perpetual calendar wristwatch for 11,000 francs. And in 1930, a jumping hour, linear-display perpetual calendar pocket watch was sold for 14,100 francs.

The Breguet desk clock no. 3142 is lot 139 in Christie’s New York watch auction taking place on December 12, 2019. It includes the original box and archive extract, and has an estimate of US$200,000-400,000.

Back to top.