A Guide to Swiss Watch Certification and Testing, From COSC to Chronometrique+

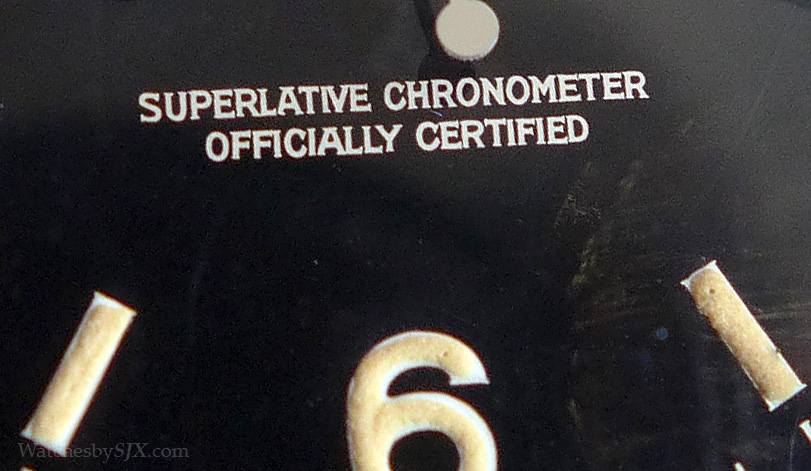

Many watches are certified, for various qualities like accuracy, durability and water-resistance, by independent agencies, ranging from COSC to TIMELAB. These certifications are proof of watchmaking and chronometric excellence, with a sprinkle of savvy marketing. Here's a handy guide to the most important Swiss watch certificates.

All watch brands conduct product quality testing in-house to make sure their watches work as they should. Some, however, go the extra mile and get their watches certified by external bodies, for that extra cachet. That mile might not actually be that far, because the external testing varies in duration, ardour and comprehensiveness. The best known and most widely used are COSC at the mass-market level and the Geneva Seal, which is issued by TIMELAB, for high-end watches made in Geneva. While TIMELAB not too long ago updated the criteria for the Geneva Seal, keeping it appropriately rigorous for a luxury watch, market leader COSC has remained constant for decades.

COSC

COSC has the lion’s share of the watch certification business, testing some 1.7 million movements annually, equivalent to about 6% of Swiss watch production. Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres, or the Association for the Official Swiss Chronometer Certification, was founded in 1973 after the Swiss observatory chronometer trials were ended in the wake of Seiko’s string of victories. It was set up by the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry, a trade association, and the five cantons where watchmaking is a major employer – Bern, Geneva, Neuchâtel, Solothurn, and Vaud.

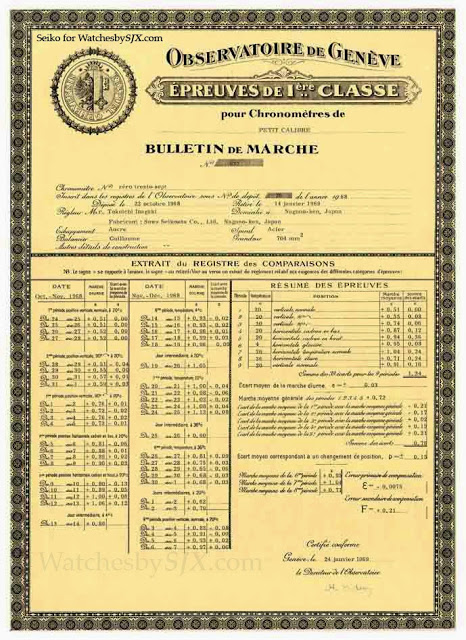

|

| An observatory trial certificate – once the gold standard in chronometry |

Its dominance is because the biggest manufacturers by volume – the likes of Rolex, Omega, Tissot and Breitling – all submit some, or most, of their output to COSC. Rolex accounts for nearly half of the COSC certificates, with practically every one of the over 800,000 watches it makes annually receiving a COSC certificate. But because COSC tests and certifies movements, both mechanical and quartz, on such a massive scale – nearly 5000 movements a day – COSC certification is a largely automated process. It tests movements – watch movements before they are cased up – to the ISO 3159 standard for chronometers.

Mechanical movements undergo a 16 day test in five positions and at three temperatures, during which they must maintain an average daily rate of between -4 and +6 seconds (for a mechanical movement of over 20 mm in diameter).

Completed movements are tested by COSC, after which they are returned to the brands for casing up. Notably, the watchmakers who submit movements for COSC testing conduct their own in-house tests after the movement put into a case. That means the actual watch that ends up on the wrist of the consumer is actually tested in-house and not by COSC.

Compared to other certification processes, COSC is not exceptionally stringent. The pass rate for COSC certification exceeds 95%. A certificate is issued by COSC once a movement passes, but not all brands include the certificate with the watch. And even if they do, the amount of information revealed varies. The most detailed certificates can include the timing results of each movement in each position. Afterwards COSC stores the test records for each movement for five years.

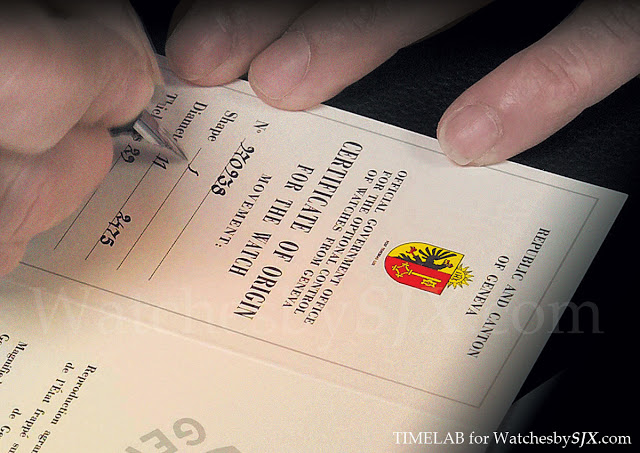

Geneva Seal

Whereas COSC is concerned only with timekeeping, the Poinçon de Genève, or Geneva Seal, requires both functional quality as well as movement finishing to meet certain standards. And as the name implies, it is also geographical – the watch has to be made in Geneva. However, this multi-faceted criteria is actually a relatively new development.

Historically the Geneva Seal was only concerned with two attributes: being made in Geneva, and decorative finishing, requiring polished screw heads with chamfered edges and slots for instance. As a consequence, the Geneva Seal was in the past issued to watches which were finished to the requisite standard, whether they actually worked reliably or not.

Additionally, only sample movements needed to be submitted for certification, after which all movements of the type would get the seal. Whether subsequent batches of movements lived up the same standard depended purely on the industriousness of the manufacturer. Passed into law in 1886 by the Cantonal government of Geneva, it was originally conceived to protect Geneva watchmakers, which traditionally made higher-end timepieces, against shoddy watches falsely claiming to be made in Geneva. That is why watches which qualify for the seal must be assembled, adjusted and cased-up in Geneva.

For most of its existence the Geneva Seal was found on watches from Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin, the two flag bearers of traditional Geneva watchmaking. But as mechanical watchmaking came back into fashion in the eighties and nineties, they were joined by brands as diverse as Gerald Genta and Chopard. But the seal barely changed since its inception and changes were long overdue. One of the events that served as a catalyst was Patek Philippe, which after more than a century of using the Geneva Seal, dropped it in favour of its proprietary Patek Philippe Seal in 2009.

TIMELAB, the body which took over administration of the seal from the Geneva School of Watchmaking, announced sweeping upgrades to the Geneva Seal standards in 2011. These came into effect in 2012. The current standards for the Geneva Seal include all the traditional movement decoration required of a high-end watch, like wheels of the going train “must be chamfered above and below.” But they extend to functional aspects of the cased-up watch as well.

These are fairly exhaustive requirements. For instance, after seven days of testing the watch must not exceed a minute’s variation from the original reading. And if it is a chronograph, the chronograph must be run during the first 24 hours of the test. Additionally, watchmakers must test every watch that receives the Geneva Seal, with TIMELAB conducting surprise audits at least 12 times a year to ensure compliance.

Now the Geneva Seal is a key symbol of quality and market positioning for several brands, primarily in the Richemont Group – Cartier, Roger Dubuis and Vacheron Constantin. A notable new entrant is Louis Vuitton, which plans to have all its high complications carry the Geneva Seal, once its new Geneva manufacture is ready later in the year.

While the comprehensive nature of the Geneva Seal is a recent development, the Fondation Qualité Fleurier, or Fleurier Quality Foundation (FQF), was set up in 2001 to do exactly the same. Set up by brands based in the town of Fleurier, Chopard, Bovet as well as Parmigiani (and its sister company Vaucher), the FQF is an independent body which tests and certifies individual watches with the FQF seal. Its test criteria is comprehensive, combining COSC, Chronofiable and Fleuritest, in addition to production and movement decoration standards.

To start with, watches with the FQF seal must be Swiss made – in their entirety. This means the whole watch, aside from the strap and clasp, must be made in Switzerland. In fact, while the raw materials for the watch can be imported, all manufacturing – into semi-finished or finished state – must be done in Switzerland. Furthermore, decoration and assembly has to be performed in Switzerland. This is far more rigorous than the “Swiss Made” standard established by the Swiss government, which call for 50% of the value of a watch to be Swiss with debates currently under way to raise this to 60%.

|

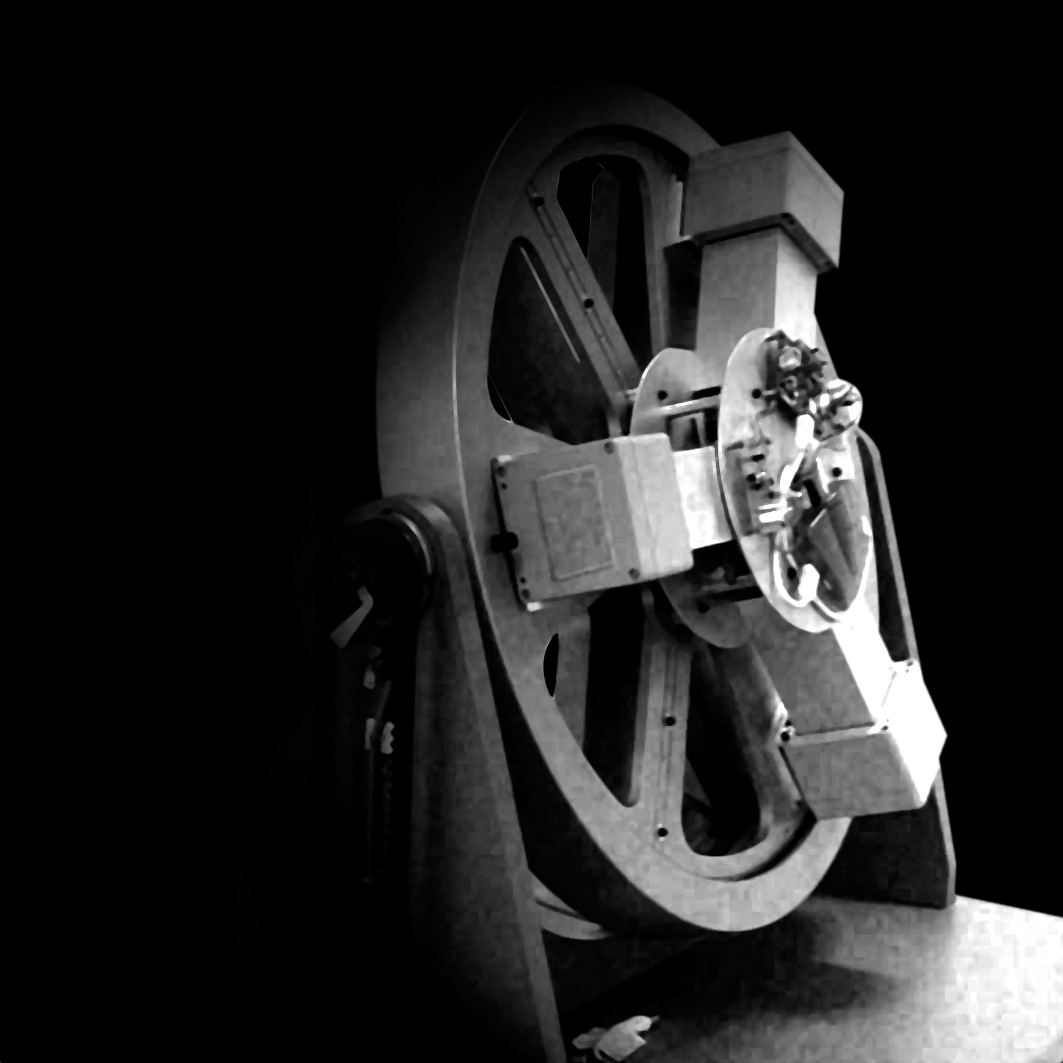

| The Fleuritest |

Besides the place of manufacturing, FQF also requires watches to meet movement decorative standards similar to that of the Geneva Seal. And like the Geneva Seal FQF also tests for functionality, using a specially developed machine to simulate actual wear.

Known as Chronofiable, the test is performed by Laboratoire Dubois, a La Chaux-de-Fonds based independent testing agency. It tests a watch over 21 days, simulating six months of wear. This includes subjecting the watch to 20,000 shocks, and also pulling apart bracelets and straps. The goal of Chronofiable is to reveal defects in production runs, so it tests samples of five to 40 watches from each batch.

The proprietary Fleuritest is the last stage of the FQF testing, which is done for individual timepieces. This simulates wear on a wrist over a 24 hour period by attaching the watch is strapped to a Fleuritest machine, which then replicates the various actions of an average wearer throughout the day, ranging from office work to sports. The watch must not exceed a gain of five seconds during the Fleuritest. Impressive as it is, the FQF seal unfortunately never caught on beyond the three founding brands, which limits its appeal.

Seeking to combine comprehensive testing with a wider audience is the newly announced Chronometric+ Observatory. Run by TIMELAB, the same body that administers the Geneva Seal, will test individual, cased-up watches to ISO 3159, the same standard COSC uses. But Chronometric+ will go a step further by testing for water resistance, magnetism resistance, power reserve and timekeeping on the wrist. Like the Geneva Seal, Chronometric+ testing is carried out by the watch brands themselves inside their factories, with unannounced audits by TIMELAB inspectors several times a year to make sure things are in order.

Chronometric+ is open to all watches which qualify as “Swiss Made”, which opens it up to a vast swathe of the watch industry. While it’s too early to determine how well its catches on, Chronometric+ might just be the push required for COSC to revamp its test standards.

As watchmakers all pursue the common goal of making their brands most prestigious and exclusive, independent testing and certification is an attractive solution. Despite the competition, dislodging COSC or the Geneva Seal from their respective positions is practically impossible. The only niche that is still unfilled is a certificate for a high-end watch made outside of Geneva, and it remains to be seen who will clinch the spot.

Back to top.