An Excursion into the Concept of Value in Mechanical Watches

SJX discusses what is value for money in relation to mechanical watches.

Value – the worth of a watch relative to its price – is a favourite topic now, given the lacklustre for high-end watches. Value for money, value propositions, bang for the buck – these phrases bandied about, sometimes callously, even right here. But what do they really mean?

Value is relative and value is distinct from price – it depends on the intrinsic qualities of the watch, as well as the price of alternatives or substitutes. A poorly put together watch from a low-end brand at a low price might be cheap, but it isn’t value. Ideally the ultimate in value is a well made watch from a premium brand at an bargain price, but that is wishful thinking.

Brand value

The concept of value can be better grasped when broken down into discrete categories. One of the most obvious forms of value a watch buyer can enjoy is value vis a vis the brand. Value in this sense would be an affordable watch from an otherwise very expensive brand.

This sort of value is getting more common as the luxury watch industry responds to the slowdown by introducing more, or more affordable, entry-level watches. Flag bearer of high-end German watchmaking A. Lange & Söhne, for instance, recently unveiled the Saxonia Thin 37mm, which at under US$15,000 is 20 percent less expensive than the previous entry-level model. Similarly, the new Quai de l’Île in stainless steel is now the lowest price mechanical watch in Vacheron Constantin’s line-up. Ditto for the Greubel Forsey Signature 1, and the list goes on.

Going downmarket with more affordable watches is a straightforward strategy. It can be an immediate solution if a watch brand is content to make a smaller margin on the entry-level watch by selling it at lower price, hopefully to sell more of them.

But the appeal of such watches are contingent on the brand’s equity remaining valuable (no pun intended). A US$15,000 Saxonia is only good value for money so long as A. Lange & Söhne is regarded as Germany’s best watchmaker.

The irony is that a callous and hasty plunge into entry-level watches can undermine brand equity as it is chipped away bit by bit. Daniel Roth is a cautionary example, having been a revered independent watchmaker of the 1990s, being the equivalent of what F.P. Journe is today. But the Daniel Roth brand has since faded away, though Roth the man is still very much alive and productive. The catalyst for the brand’s decline was arguably its decision to go offer more affordable but less well made versions of its timepieces when business slowed in the late 1990s.

Making complications simpler and cheaper

More challenging for a watch brand to pull off, but sometimes offering more satisfaction to the buyer, is value for money in terms of complications. The value for money here is obvious: a particular complication for less than what it usually costs. Recently several watch brands have done that with various complications – TAG Heuer with its US$15,000 Heuer-02T tourbillon (that has a chronograph to boot), while the perpetual calendar has been made a lot more affordable by Montblanc and Frederique Constant.

Accomplishing this usually requires two competencies: a clever watchmaker to simplify the complication, and industrial production on a largish scale. Several TAG Heuer executives have stated publicly that a key factor behind the price of the Heuer-02T tourbillon was streamlining the traditional manufacturing process.

Making complications cheaper often and aggressively, however, eliminates most of their appeal. The split-seconds chronograph is a cautionary tale. Historically the complication was revered, regarded as being on par with the minute repeater in terms of complexity. Movements like the modern day Patek Philippe calibre CHR 27 embody the qualities of a traditional, high-end split-seconds chronograph movement, which are almost quixotic today.

The split-seconds chronographs has lost that cachet, being seen as fancy chronographs today, rather than a complication in the class of a repeater. The decline of the split-seconds can be traced to Baselworld 1992, when a slew of low-priced and heavily simplified rattrapante chronographs were introduced.

IWC’s Portugieser split-seconds is the best known, with its mechanism designed by Richard Habring, who managed to simplify it tremendously. In the same year Chronoswiss unveiled its own rattrapante (powered by a movement conceived by Alfred Rochat), while movement maker Jaquet-Baume (now La Joux-Perret) debuted its split-seconds movement that was used by Ulysse-Nardin amongst others.

These three movements were proof that great minds think alike: all of these them were based on the economical Valjoux 7750, a favourite for its modest cost and robustness.

Because complications are mechanical constructions, essentially technology, they do usually get more cost-effective as production techniques improve and engineers get smarter. The same happens in automobiles: features pioneered in luxury models eventually filter down to affordable cars.

The impact of technology progress extends to other more decorative aspects of a watch, like sapphire crystal for instance. They are now found even on low-end watches. More complex sapphire crystal shapes, like those that are domed or “box-shaped”, are also becoming more common on mid-priced watches like the Longines RailRoad or TAG Heuer Carrera Telemeter.

Even traditional artisanal crafts – the esteemed metiers d’art in watchmaking parlance – can be made more affordable with technology. Dials finished in vitreous enamel, usually called grand feu, are more accessibly priced thanks to production techniques that are secret. Both Breguet and Blancpain (sister companies in the industrial behemoth Swatch Group) offer enamel dial wristwatches for less than the equivalents made by rivals like Vacheron Constantin for that very reason. And Seiko does even better with its US$3000 mechanical chronograph with an enamel dial; the dial is made via an entirely automated process.

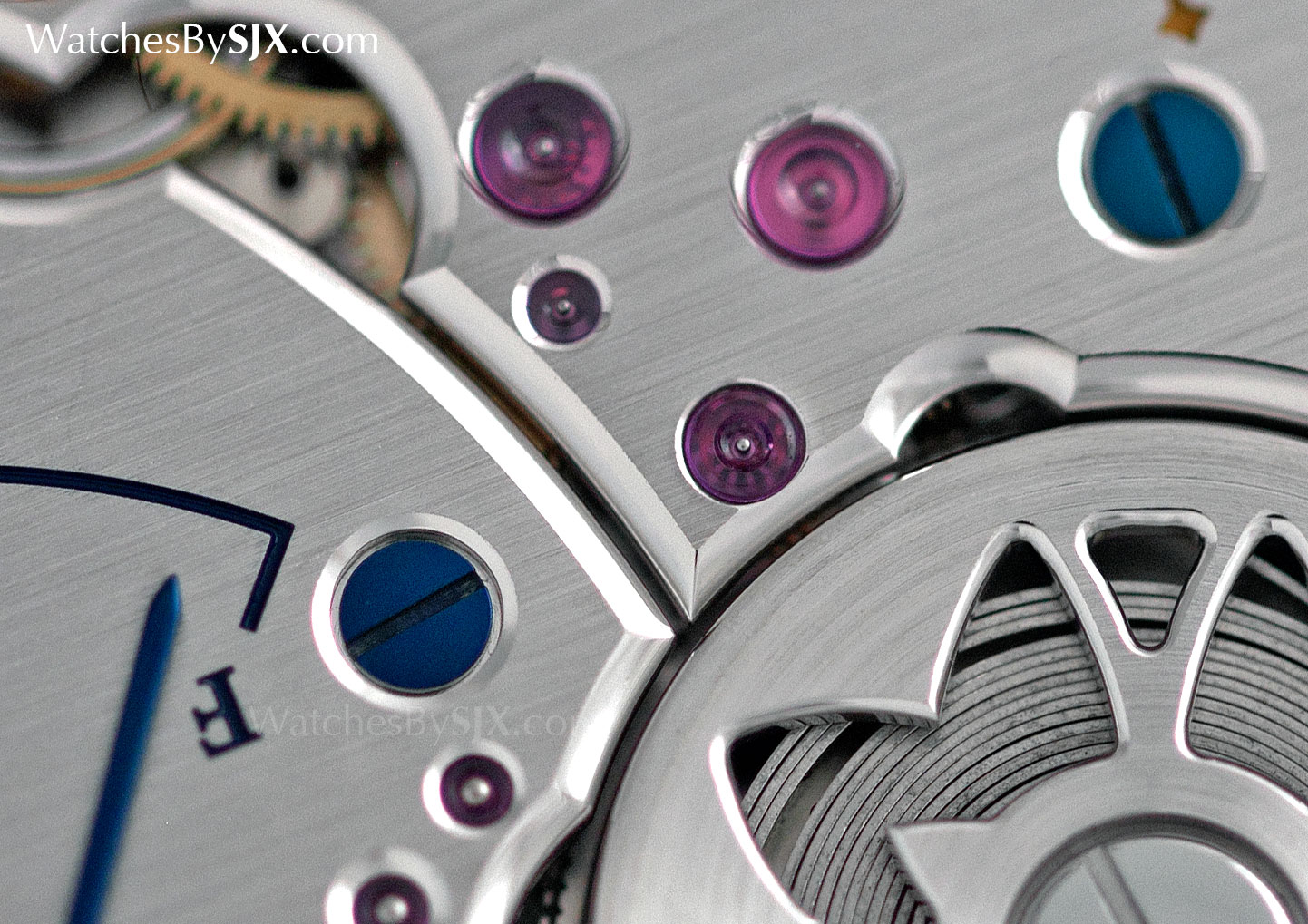

The value in finishing

And then there is value for money where brands offer better quality – usually in the form of finer movement finishing – for less. This can be found at all levels of the price spectrum, with corresponding standards of finishing.

At the affordable end Nomos is a standout. The German watchmaker puts in sufficient effort into finishing its movements, with mechanically applied finishing augment with a bit of hand-finishing, leaving them appealingly decorated.

At a higher price point the same holds true for the Seiko Credor Eichi II. An expensive watch by any standard, with a retail price in excess of US$60,000, the Eichi II is nonetheless value given the quality of the movement decoration. That is all done by hand, and to a standard found only in more expensive watches; in fact one can convincingly argue the Eichi does even better than its peers like the Voutilainen Vingt-8.

While even high-end complications can be reduced by technology and scale, top-end hand-finishing remains, for the foreseeable future, exclusive to skilled artisans. Value for money in this regard is consequently more durable.

Vintage watches

Vintage watches are another expansive topic on its own, but worth touching on since they regularly cited as being excellent value for money.

That argument is often advanced on two reasons. The first being vintage watches offer features that are extremely expensive in their modern equivalents. A traditionally constructed chronograph with column wheel and lateral coupling costs a lot less in a vintage watch than it does in a contemporary timepiece. The second is the added heft of history and provenance – Paul Newman, Steven McQueen, the Shah of Iran!!! – gives them an intangible but discernible extra potency. Such provenance is intuitively genuine; it cannot be concocted by a marketing department.

Both are valid assertions, but a prudent collector should keep in mind two equally important facts. The value proposition of vintage watches diminishes as prices increase, which is now happening at a rapid clip.

More importantly, many bang-for-the-buck vintage watches were, in their day, inexpensive or mid-range timepieces. Consequently, they were manufactured and finished as such.

Vintage chronographs from the likes of Longines, Tissot, Universal Geneve, Heuer and so on, are sought after and quite valuable today. But when they were new these were mid-range watches. Even though many are powered by movements that would be regarded as high-end today (think Breguet overcoil, column wheel, lateral clutch and so on), such features were commonplace in that era.

Back to top.