Complicated Collectors: Seth Atwood

The Time Museum and its legacy.

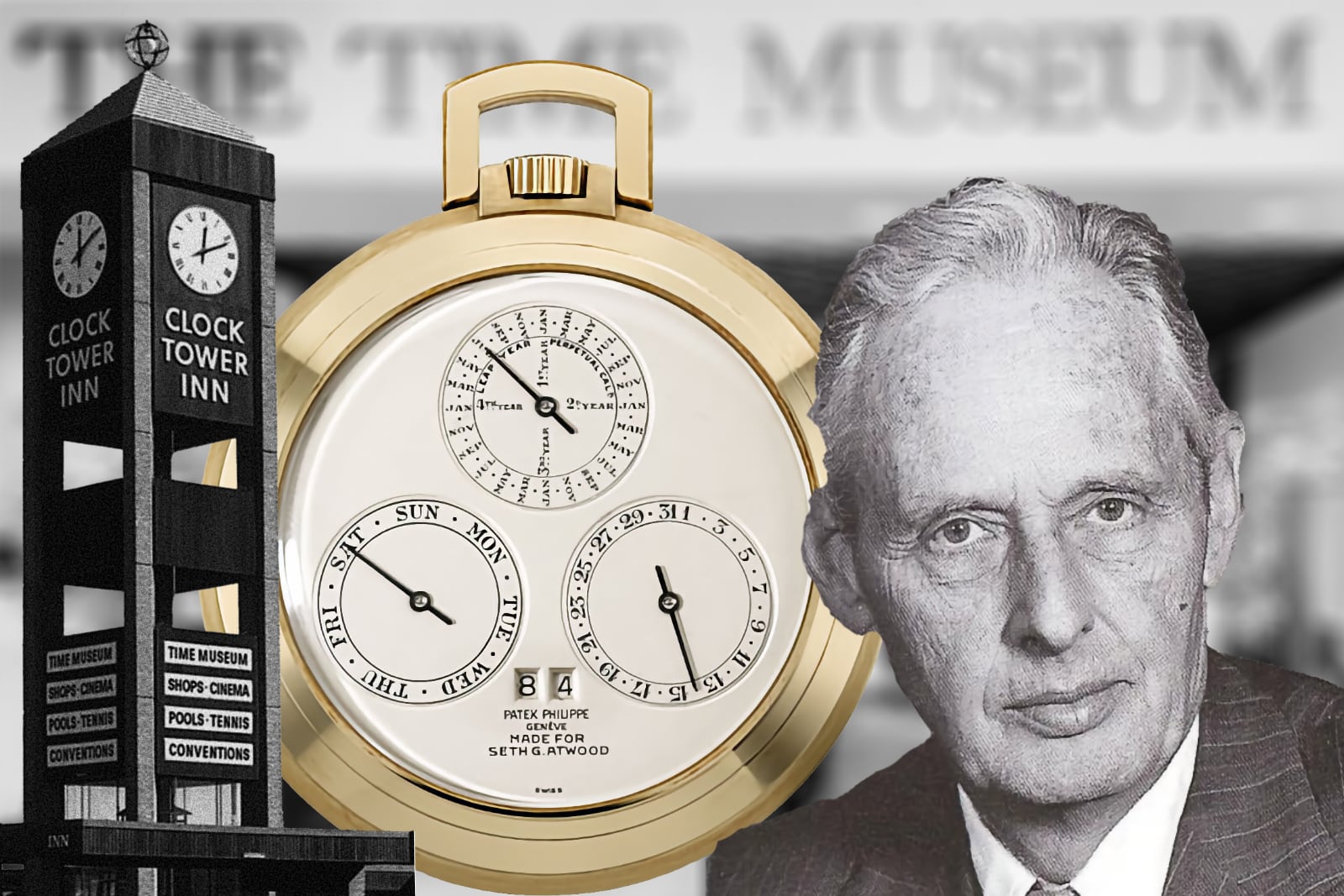

In the late 1970s, anyone serious about horology would eventually find themselves in Rockford, Illinois, about 90 miles west of Chicago. Visitors stayed in a hotel near a motorway that happened to be home to many of the world’s greatest clocks and watches. The collection of Seth Atwood sat below the everyday hum: Roman sundials beside Islamic astrolabes; marine chronometers alongside French regulators; English pocket watches paired with American factory movements; and, at the far end, atomic clocks.

Rockford was a town that built machine tools and industrial equipment, so the hotel naturally served business travellers and convention attendees. But among them were watchmakers who flew in from Europe and Asia to see mechanisms they couldn’t examine anywhere else. For nearly three decades, one man’s vision put Rockford on the horological map.

The 1972 secular true perpetual calendar Patek Philippe ref. 871, made for Seth G. Atwood. Image – Christies/collage

Rockford native Seth Glanville Atwood was born in 1917, into a world of industrial logic. His father had started the Atwood Vacuum Machine Company a year earlier, its first product a simple spring-loaded bumper that kept car doors from rattling. Detroit needed millions of them, and the company grew from there, supplying window regulators, door hardware, and other practical parts in volume.

Seth grew up around engineers and production managers who solved problems with their hands. After Stanford, Harvard Business School, and a stint in the Navy, he came home to run the family firm, pushing it beyond its automotive roots into appliances and industrial equipment until, at its height, it employed thousands.

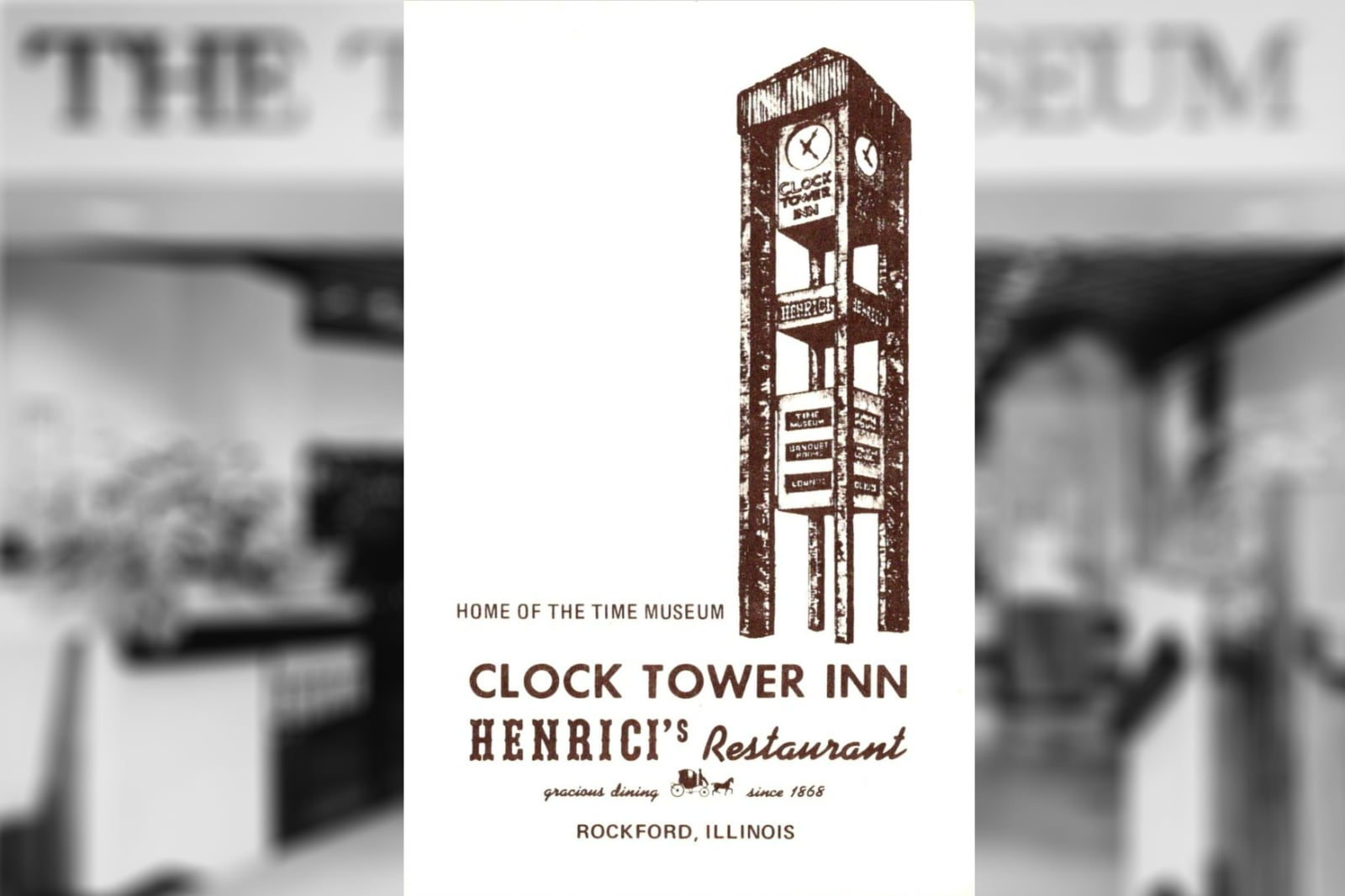

Atwood also expanded the family business and invested in real estate. In the early 1960s, he developed a motor lodge and conference centre outside Rockford. He called it the Clock Tower Inn. At first, the name was incidental, but within a decade it would house one of the most significant horological collections ever assembled.

Early acquisitions

Atwood had been buying timepieces since he was 17: he collected sundials, water clocks, and early watches. He was interested in astronomy and physics and thought about time as a technical problem. But for three decades, the collecting stayed casual; he bought what crossed his path, with no larger plan.

That changed in 1968. Atwood flew to London for a Sotheby’s auction and bought a quarter-repeating watch by Thomas Tompion in a gold pair case hallmarked 1697. He paid £4,000, a record for an English watch at the time, equivalent to about £61,000 today. English collectors questioned the price, and dealers worried his spending would inflate the market. Atwood ignored them; the watch was early, important, and by Tompion.

Clock Tower inn ad. Image – private collection/collage

A California-based collector who had been the underbidder called him after the sale, telling Atwood he regretted not having gone even higher. The man who lost was confirming that Atwood had acquired a masterpiece for less than its true worth. Atwood told that story for years afterwards to make the point that when you see the right piece, you act. Hesitate, and it goes to someone else. The casual hobby was over; a mission had begun.

From that moment, the collecting acquired a purpose. Atwood decided to do something no single individual had ever attempted: to document the complete history of how humans had measured time, from the earliest shadow markers to modern atomic standards. It was an industrialist’s approach to connoisseurship. He asked Robert Foulkes, secretary of the Antiquarian Horological Society, for a list of important makers, and Foulkes compiled around 200 names from G.H. Baillie’s reference book. Atwood treated it like a production checklist. If a piece filled a gap in the technical progression, he bought it. If it didn’t, he passed.

Clock Tower inn flyer. Image – private collection/collage

Dealers learned he was a different kind of collector: he didn’t bargain, and he was decisive. They brought items to Rockford, where Atwood would examine them, ask questions, and make a decision, often on the same day. If he wanted something, he wrote a cheque for the asking price. This reputation spread quickly, giving Atwood a kind of de facto first right of refusal for important watches.

The Time Museum

The Time Museum opened in 1971 on the lower level of the Clock Tower Inn. The galleries moved chronologically through 14 sections, from “Early Instruments of Time Measurement, 3000 BC–1275 AD” to “Continuing Refinement of Frequency, 1945 to the Present.” His wife, Patricia, designed the interior, with its green carpets, off-white furniture, and soft lighting. She put comfortable chairs where visitors could sit and study the pieces.

One of the Time Museum exhibition rooms with the Breguet “Duc d´Orléans” in front. Image – The Time Museum postcard: private collection/collage

The museum grew quickly. By 1972, it had added new galleries covering 5,400 square feet. In 1981, another expansion created a purpose-built space of 20,000 square feet, holding over 3,000 objects. The layout made the collection feel like a physical encyclopedia. Visitors could see a Roman sundial, a Breguet tourbillon, a Wallingford astronomical clock, and an atomic standard all in one visit.

Still, the institution grew further. Specialists arrived: William Andrewes from Greenwich, Anthony Turner for French horology, and Bruce Chandler for American clockmaking. By the mid-1980s, horological scholars from around the world travelled to Rockford regularly.

The collection

The scope of what Atwood built is easier to understand by looking at specific pieces. His collection of marine chronometers was extraordinary, not just for the famous names but also for the rivals. For example, he owned chronometers by John Harrison’s contemporaries who were working on the same problem from different angles. He had pieces by Larcum Kendall, who copied Harrison’s H4 for the Board of Longitude, and work by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw, the two men who refined the detent escapement and made chronometers practical for mass production.

He also had some of Ferdinand Berthoud’s experimental pieces, which took a completely different approach to temperature compensation than Harrison’s bimetallic strip. The chronometers showed different makers attacking the longitude problem from different angles, each one refining what came before.

The same approach was applied to the pocket watch collection. The collection included early verge watches from the 17th century, when the technology was still crude, and cylinder escapement watches from the 18th century, which were more accurate but fragile. He had lever escapement watches from the 19th century, tourbillons, perpetual calendars, minute repeaters, and watches from American companies like Waltham, Elgin, and Hamilton that were pioneers of mass production and interchangeable parts.

Replica of Richard of Wallingford’s fourteenth-century astronomical clock. Image – Wikipedia/collage

He also collected industrial timekeeping equipment, factory time clocks, and railroad chronometers. Most museums passed on these pieces. They showed how timekeeping moved from the pocket of a wealthy gentleman to the factory wall, synchronising labour and production. Atwood saw the history of time as organisational: a way for societies to coordinate work and movement.

Rebuilding what was lost

The reconstructions were another aspect of Atwood’s vision that set the Time Museum apart. Most museums display what survives; Atwood displayed what should have survived. When he learned that Richard of Wallingford’s 14th-century astronomical clock at St Albans had been destroyed during the Reformation, he commissioned a reconstruction based on Wallingford’s manuscripts. When he learned that Giovanni de Dondi’s Astrarium, one of the most complex mechanical devices of the medieval period, existed only in drawings, he had it built. Atwood approached these scholarly projects with the same rigour as an archaeological reconstruction.

Drawing of Su Sung clock eleventh-century Chinese water-powered astronomical clock. Image – Wikipedia/collage

The Su Sung clock was particularly ambitious. It was an eleventh-century Chinese water-powered astronomical clock that combined a celestial globe, an armillary sphere, and a striking mechanism. The original was destroyed in the 12th century, and all that remained were descriptions in Chinese texts. Atwood funded a team of scholars and craftsmen to build a working version based on those texts.

The result was a massive machine, over 30 feet tall, that demonstrated principles of gearing and escapement that wouldn’t appear in European clocks for another 300 years. It was one of the museum’s most popular attractions, making abstract historical knowledge concrete.

Atwood also built a research library alongside the collection, systematically acquiring rare horological books. The library included first editions of the major texts from innovators like Huygens, Harrison, Breguet, and Daniels. He collected auction catalogues dating back to the 18th century in order to piece together records of what had been made, who owned it, and what it sold for.

The collection of books was a major draw for scholars like Andrewes, Turner, Chandler, and Bedini, who visited Rockford to conduct research in the library.

The Breguet Simpathique made for the Duc d’Orléans. Image – Sothebys/collage

The Rockford files

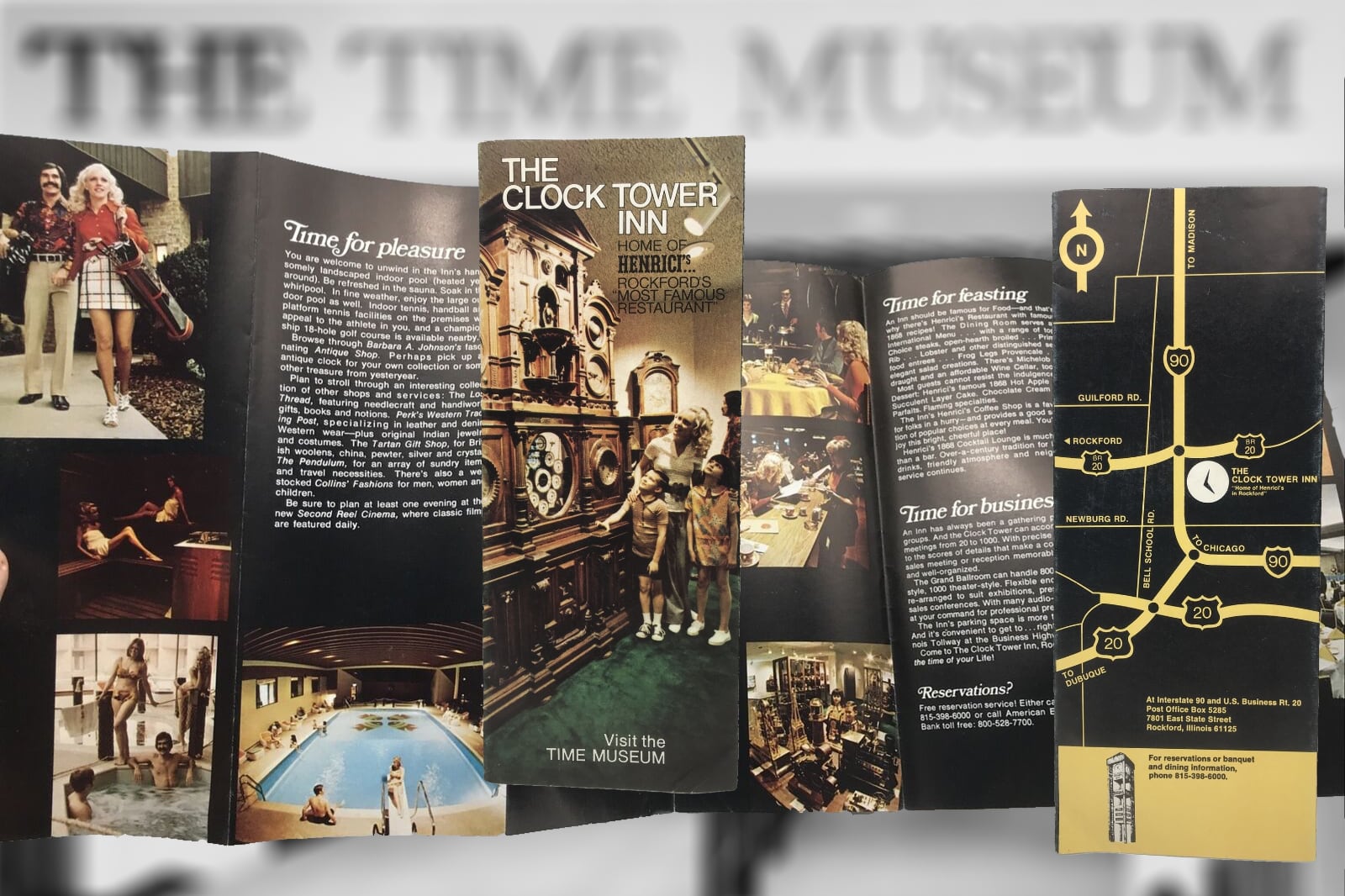

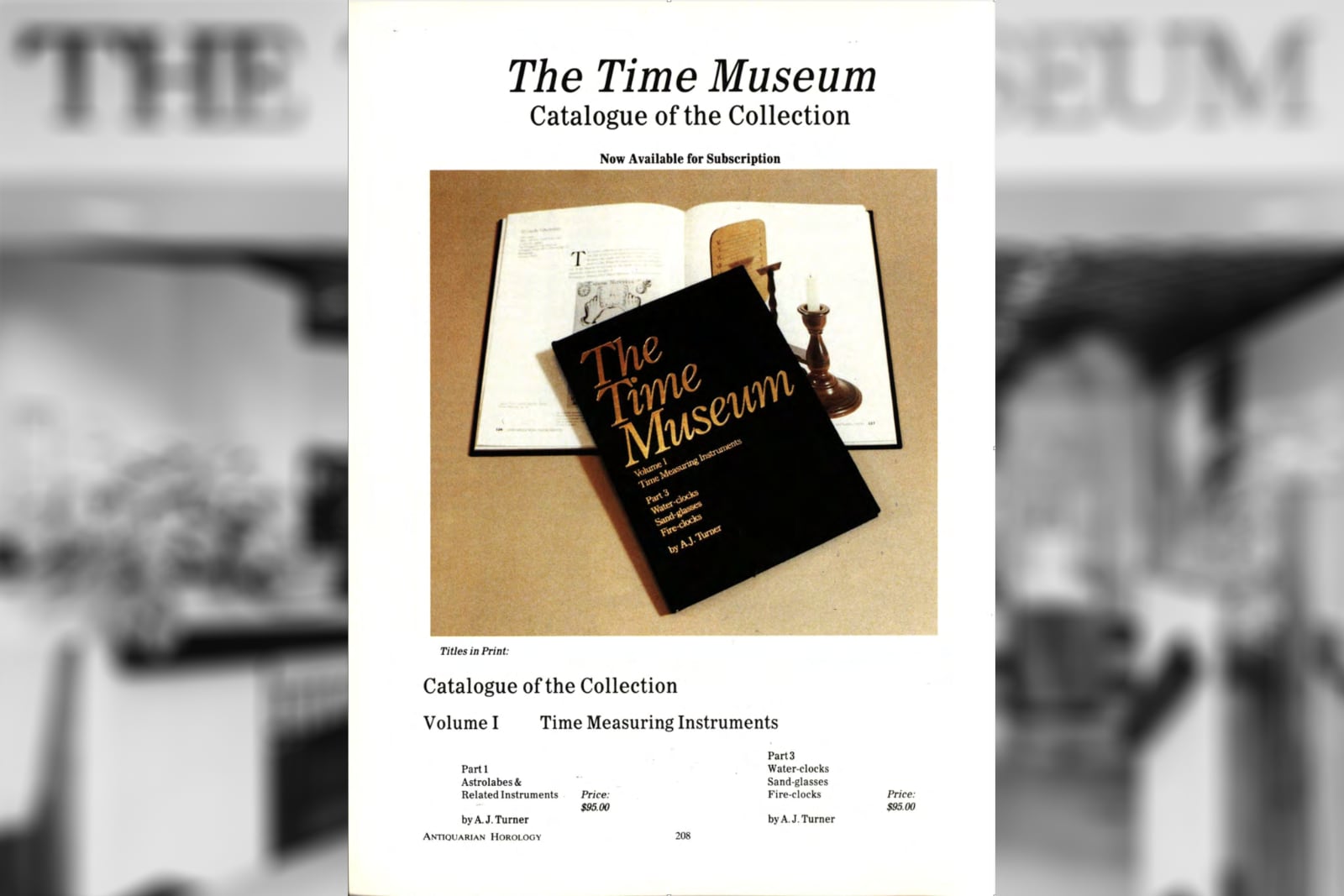

Eventually the collection became so vast it defied attempts at documentation. A great effort was made to produce a comprehensive catalogue ; Atwood expected it would require 40 volumes, one for each major section of the museum. This approach would allow every object to be documented with photographs, technical descriptions, provenance, and historical context.

Unfortunately, the museum closed before the project could be completed; in the end, only four volumes were produced. Though the project failed to achieve its objective of documenting the complete contents of the Time Museum, it was not altogether unsuccessful. Other institutions studied the four completed volumes closely; each watch was photographed from multiple angles, and the movements were described in detail. Makers were researched, and provenance was traced back through available records.

The Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva, which opened in 2001, used the Time Museum catalogues as a model, as did the Musée International de l’Horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds. When Sotheby’s and Christie’s began producing high-quality catalogues for their watch auctions in the early 2000s, they hired the same scholars who had worked on the Time Museum project. The approach Atwood pioneered, treating watches as objects worthy of serious scholarly attention, became the industry standard.

An early patron to independents

The patronage of living watchmakers was perhaps the most radical part of Atwood’s vision. While other collectors looked exclusively to the past, Atwood invested in the present. His relationship with George Daniels is the most famous example. When Atwood commissioned his watch in 1974, Daniels was respected but not yet legendary. This early commission helped give Daniels the financial freedom to pursue his most ambitious ideas.

The resulting watch was a masterpiece, and the escapement he developed for it, the Co-Axial, was later adopted by Omega and is now considered one of the few fundamental inventions in watchmaking since the 18th century.

Richard Good´s triple axis tourbillon. Image – Sothebys/collage

Atwood also funded Richard Good and Anthony Randall. Good built a triple-axis tourbillon, a mechanism so complex that few watchmakers had yet attempted it. Randall investigated constant-force escapements and multi-axis tourbillons, exploring the theoretical physics of timekeeping. Neither project had promising commercial applications; Atwood effectively paid them to experiment.

Dispersal

As the 1990s progressed, Atwood, now in his late 70s, began planning his final act. He saw the museum as his life’s work, but he believed its purpose was fulfilled once the watches had been displayed, studied, and documented. In other words, the physical collection was mortal, but the knowledge it contained could be made permanent. The Time Museum closed in 1999, and Sotheby’s dispersed the collection through a series of auctions over the next five years.

Atwood planned the dispersal carefully with Sotheby’s, organising the sales thematically. The first sale focused on early timekeeping: sundials, astrolabes, and water clocks. The second covered clocks from the 16th through the 19th centuries. The third offered pocket watches and marine chronometers. The fourth presented complications and automata. Each sale had a catalogue that functioned as a reference work.

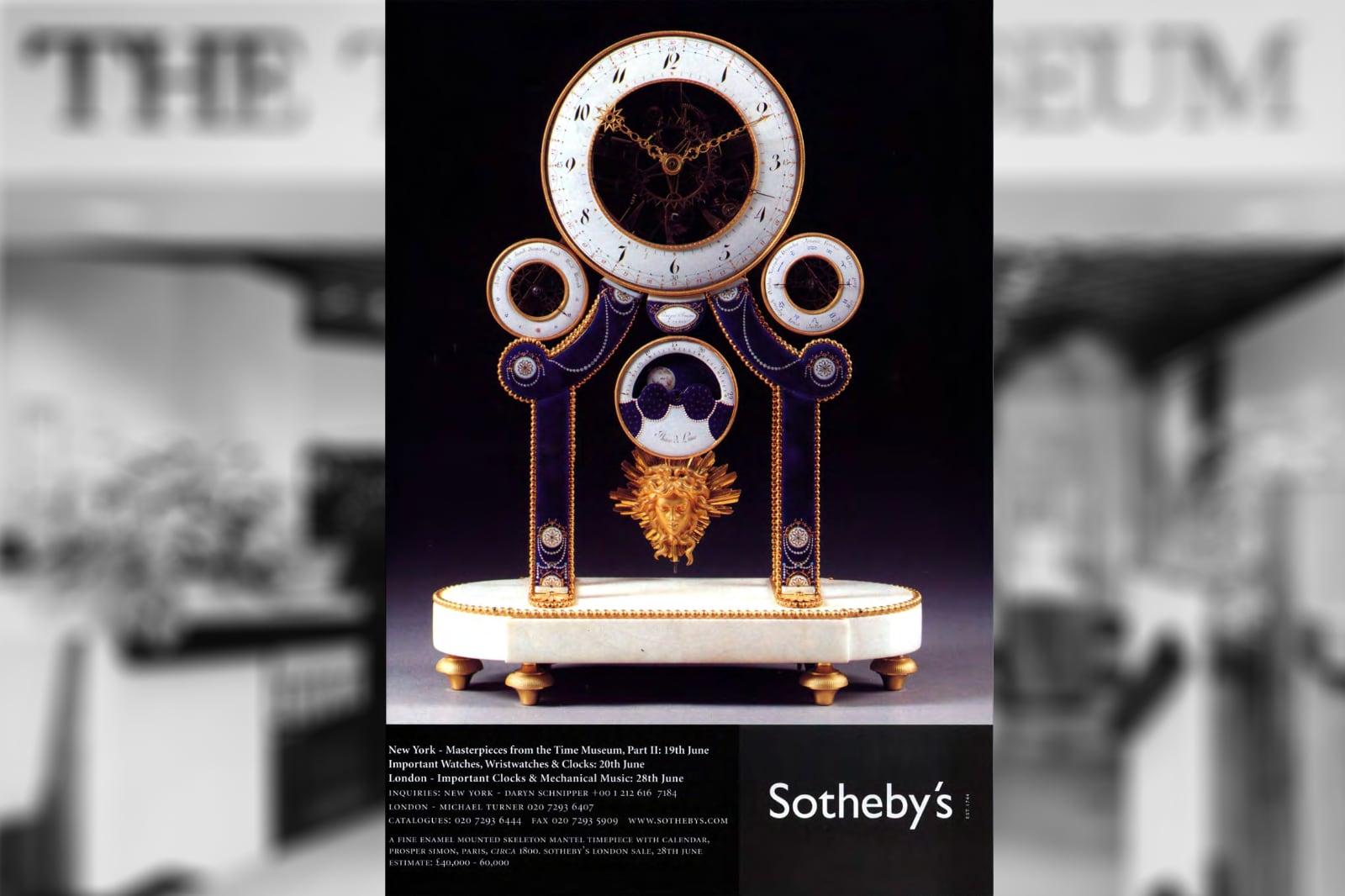

Ad published by Sotheby’s announcing Part II of the Masterpieces of The Time Museum sale . Image – Sotheby’s/collage

Atwood ensured each sale was accompanied by meticulously researched catalogues, turning the dispersal into a final act of publication. The pieces scattered, finding new homes in museums and private collectors worldwide. The Tompion watch that started it all went to a museum in Basel. The physical collection was gone, but the information gathered for the catalogues lived on.

The Henry Graves Jr. Supercomplication was the star of the 1999 sale. It was the most complicated watch ever made, commissioned by a New York banker in 1925 and completed by Patek Philippe in 1933. It had 24 complications, including a perpetual calendar, a minute repeater, and a celestial chart of the night sky over Graves’ home in New York. When it sold for US$11 million, it shattered the previous auction record for a watch and made international news, putting horology on the map as a serious collecting category comparable to fine art.

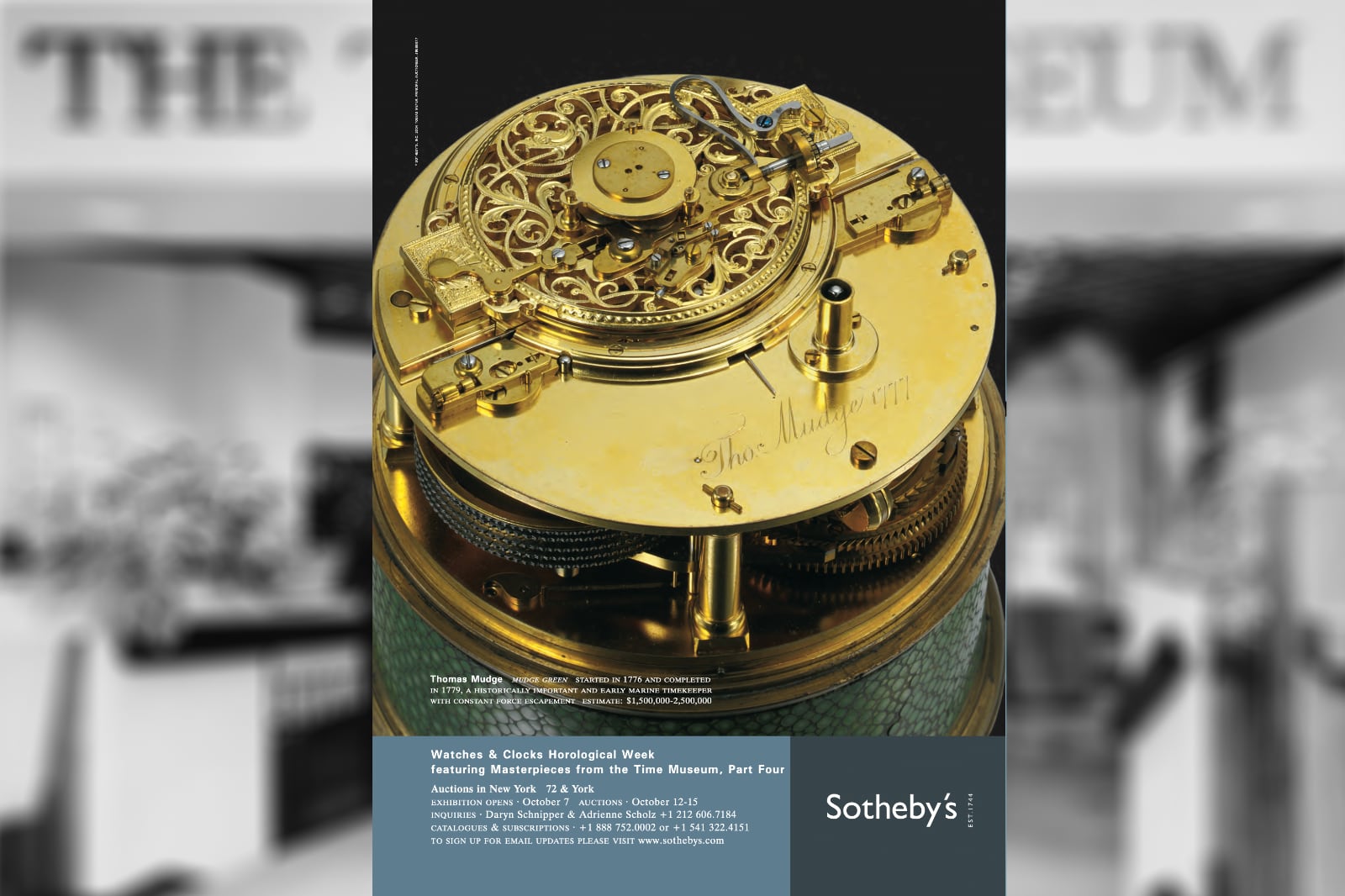

Ad published by Sotheby’s announcing Part FourI of the Masterpieces of The Time Museum sale . Image – Sotheby’s/collage

But the Graves watch was just one masterpiece amongst many. The remarkable Breguet Sympathique “Duc d´Oléans” that sold for US$5.7 million was equally significant, a clock with a special cradle that automatically wound and set a pocket watch placed in it overnight, of which only a handful were ever made. The Tompion grande sonnerie bracket clock that sold for over $2 million was a masterpiece of English clockmaking from the early 18th century. These were historically important pieces that anchored the collection Atwood had built over the past 30 years.

The later sales in 2002 and 2004 dispersed the scientific instruments, marine chronometers, and Atwood’s contemporary commissions. Anthony Randall’s double-axis tourbillon carriage clock sold for a strong price, as did Richard Good’s triple-axis tourbillon. These results validated Atwood’s belief that supporting living horologists was as important as collecting historical pieces, and helped the market recognise that these modern works belonged in the same conversation as the masterpieces of the past.

The Time Museum Catalogue of the Collection, Volume 1 . Image – AH/collage

The Atwood legacy

Fragments of the Time Museum collection can still be seen all over the world; many pieces remain on display to the public. The British Museum acquired several astrolabes, while the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York bought some early clocks. The Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva acquired a significant portion of the pocket watch collection, including the Sympathique “Duc d´Orléans”. From time to time, pieces from the collection continue to resurface, like this Patek Philippe ref. 767.

But the knowledge did not disappear. The catalogues, research, and documentation were preserved, enhancing the body of public horological knowledge we now take for granted. Scholars still cite the Time Museum catalogues, and auction houses still rely on their provenance records. The standards Atwood established for organising, documenting, and presenting horological material have since become foundational. Rockford is gone, but the work endures.

Back to top.