Insight: Regulating a Mechanical Watch Movement

Gyromax, Microstella, pin regulators and more.

A mechanical watch is not always spot on; less-than-perfect timekeeping can happen, often due to an unruly oscillator. The solution is direct adjustments to the hairspring and balance assembly, either slowing down or speeding up the oscillator, a practice known as regulation. Watchmakers have devised multiple innovations to achieve this, including the free-sprung balance, exemplified by the Gyromax of Patek Philippe and Microstella of Rolex.

While a simple concept in principle, the mechanics and practice of regulation are nuanced. Here we’ll delve into the theory of regulation and the primary regulating systems: the curb-pin regulator and the free-sprung (or variable inertia) balance.

The Lange L043.4 with a screwed balance inspired by pocket watches

Basic concepts

In order to better understand watch regulation, we need to first cover some of the basic physics behind the watch oscillator:

- The component responsible for the running rate of a movement is its regulating organ.

- The regulating organ is made up of a hairspring paired to a balance, which together are also known as a harmonic oscillator.

- The natural oscillation period is the time it takes the balance to make a full swing, back and forth.

- The period is made up of two vibrations, one for each direction of the balance motion, with the escapement being unlocked at each vibration.

Notably, the natural period of a balance wheel is intrinsic to itself and does not depend on the escapement type or the going train ratio.

An oscillating system works well as a timebase because its natural frequency does not depend on external factors. The balance passes and unlocks the escapement at theoretically equal intervals, thus setting the going train discharge speed. In reality the frequency can also be affected by external factors, like friction, changes in amplitude or by the escapement action, though that is beyond the scope of this article.

The Voutilainen cal. 28 with a large balance sporting four weights

The period is the numerical inverse of frequency, so a frequency of 4 Hz results in a theoretical balance period of 0.25 seconds (one fourth of a second). In practice it is impossible to have a perfect period. But with careful regulation, the watchmaker can reduce the timing errors and obtain an acceptable running rate.

Regulation

Getting past the theory, we are getting closer to the physical act of regulating of a timepiece. There are two established ways of regulating the timing of a sprung balance: by either changing the active hairspring length or the balance wheel’s moment of inertia.

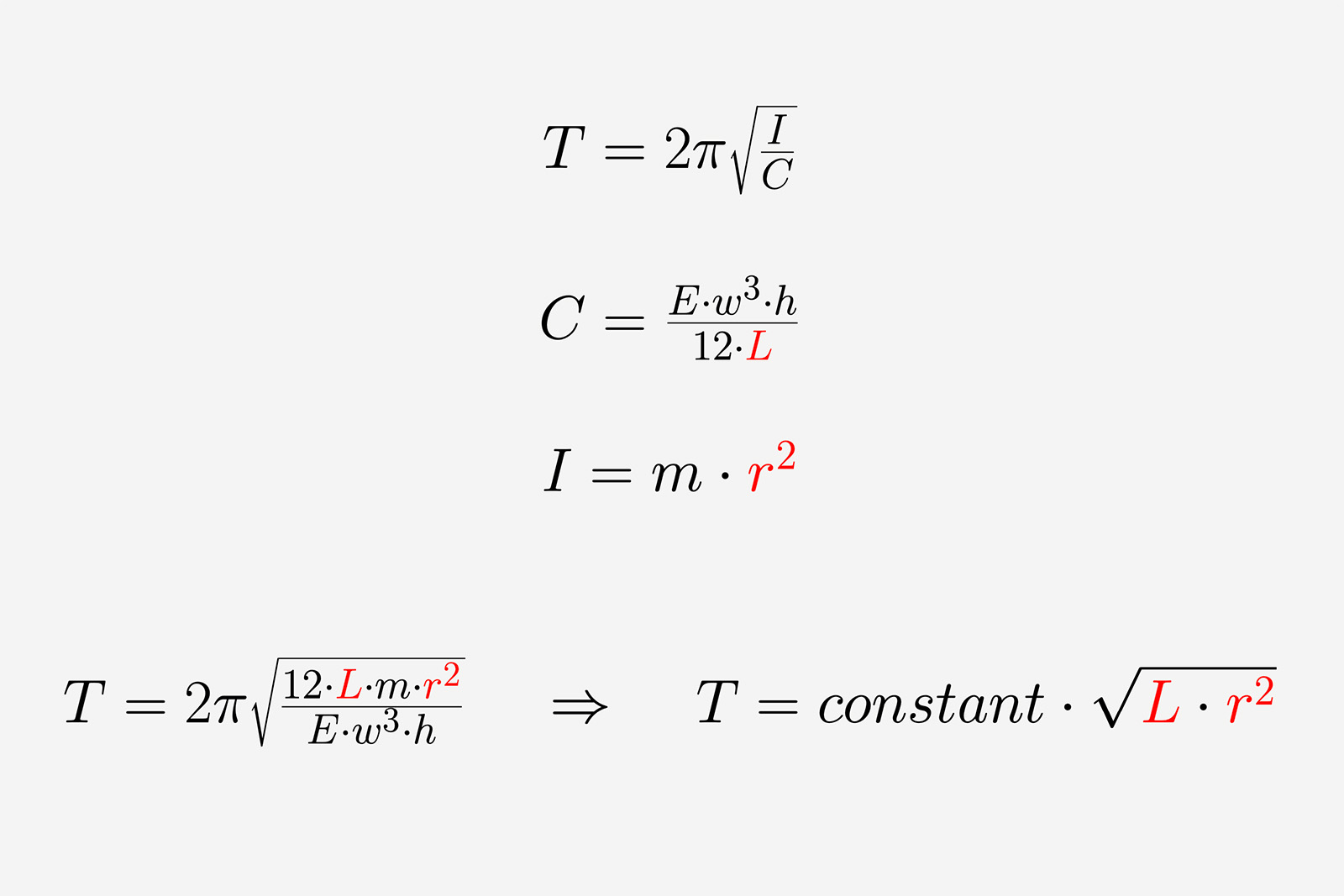

Figure 1. The terms highlighted in red are the only variables modifiable by a regulator: the active spring length and the radius where the balance mass is concentrated.

To understand why that is, we must look at the general formula for the swing period T. As seen above in Figure 1, the period is a function of the balance’s inertia moment I and the hairspring ‘stiffness’ constant C.

The constant C is dependent on the spring’s dimensions (width — w, height — h (sectional) and active length — L) and its Young modulus E (material characteristic).

The modern-day Omega cal. 3681 with a free-sprung balance, paired with a silicon hairspring and Co-Axial escapement.

By convention, the moment of inertia I is a function of the total mass m and the radius of gyration r squared. The only variables turn out to be L and r (highlighted in red) and we can comfortably write the rest off as a general constant.

It becomes clear how an increase in either L or r leads to a proportional increase of the period T. A given modification in r is more effective than a modification of L, since r is squared in the equation.

A longer swing period means the watch is running slow. That is because the balance wheel unlocks the escapement more rarely. If L or r are decreased, the swing takes conversely less and the watch runs fast.

Pin regulator

As shown before, the swing of the balance depends in part on the active length L of the hairspring. We say “active” rather than “total” because most oscillators work with longer than necessary springs, which are virtually shortened by a pin regulator.

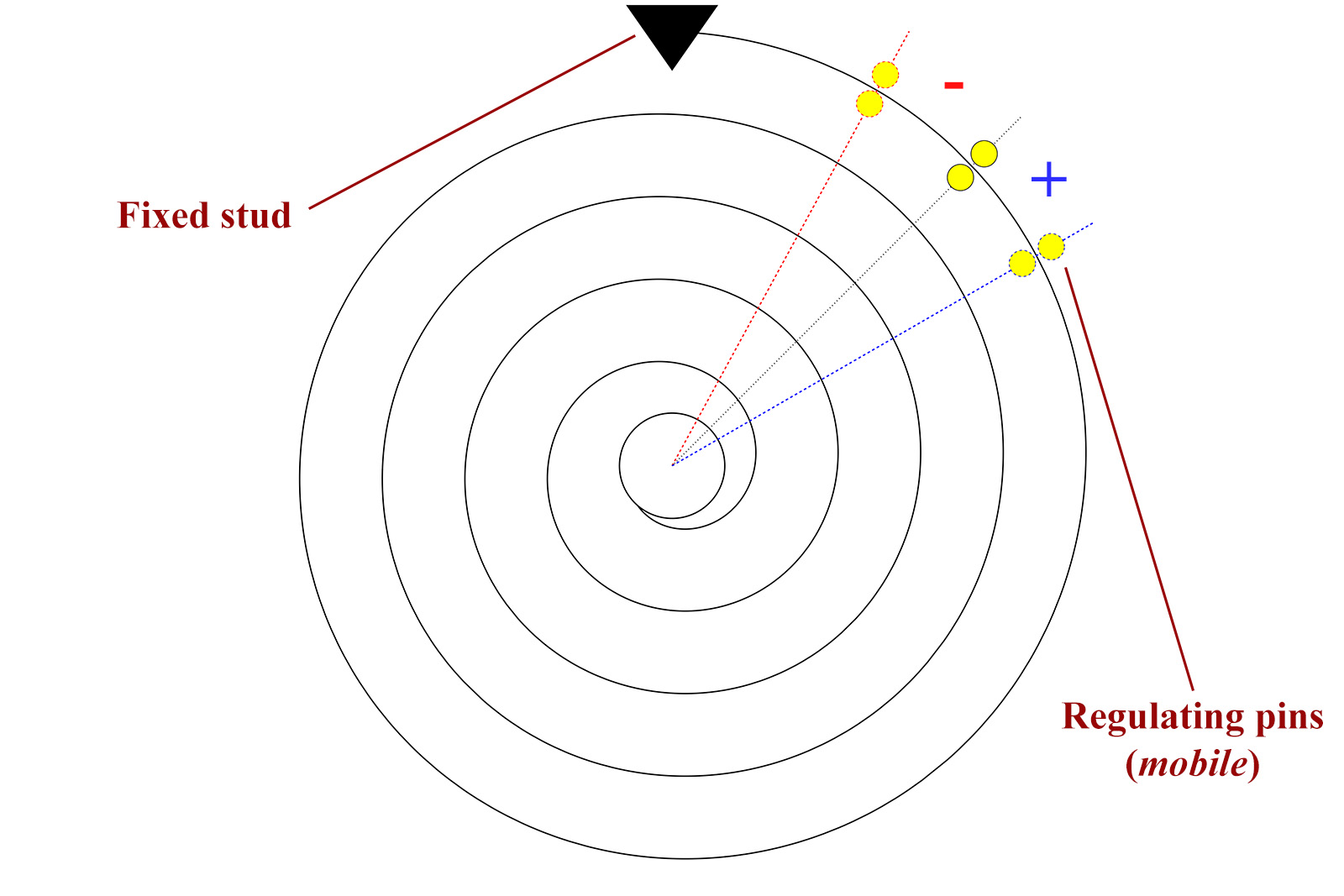

Two pins pinch on the last coil of the hairspring, effectively rendering inert the spring portion between them and the fixed stud carrier. Figure 2 shows a general embodiment of the system. From a neutral position the pins can move either left or right, lengthening (red) or shortening (blue) the active spring portion.

Figure 2. The drawing shows a basic flat spiral, with the fixed outer pinning point (stud) and the yellow pin regulator. The pins can either shorten or lengthen the active vibrating portion of the hairspring.

This kind of regulation is straightforward and can be done by any watchmaker without much difficulty. Moreover, the system is convenient to produce on a large scale and provides an easy way to quickly adjust a watch’s running rate.

Inertia weights

The swing of the balance also depends on the radius r at which the balance mass is concentrated. In practice, a balance’s mass is distributed across its whole structure and not just at a set r. Through convention all the available mass can be modelled on an imaginary circle of radius r, centred on the balance axis.

Screwed or weighted balances are a common sight among both new and vintage precision timepieces. When there is no pin regulator, the balance is called free-sprung, since the hairspring has a set and immovable length. All the regulation is carried by altering the inertia moment of the balance, by moving the weights either inwards or outwards.

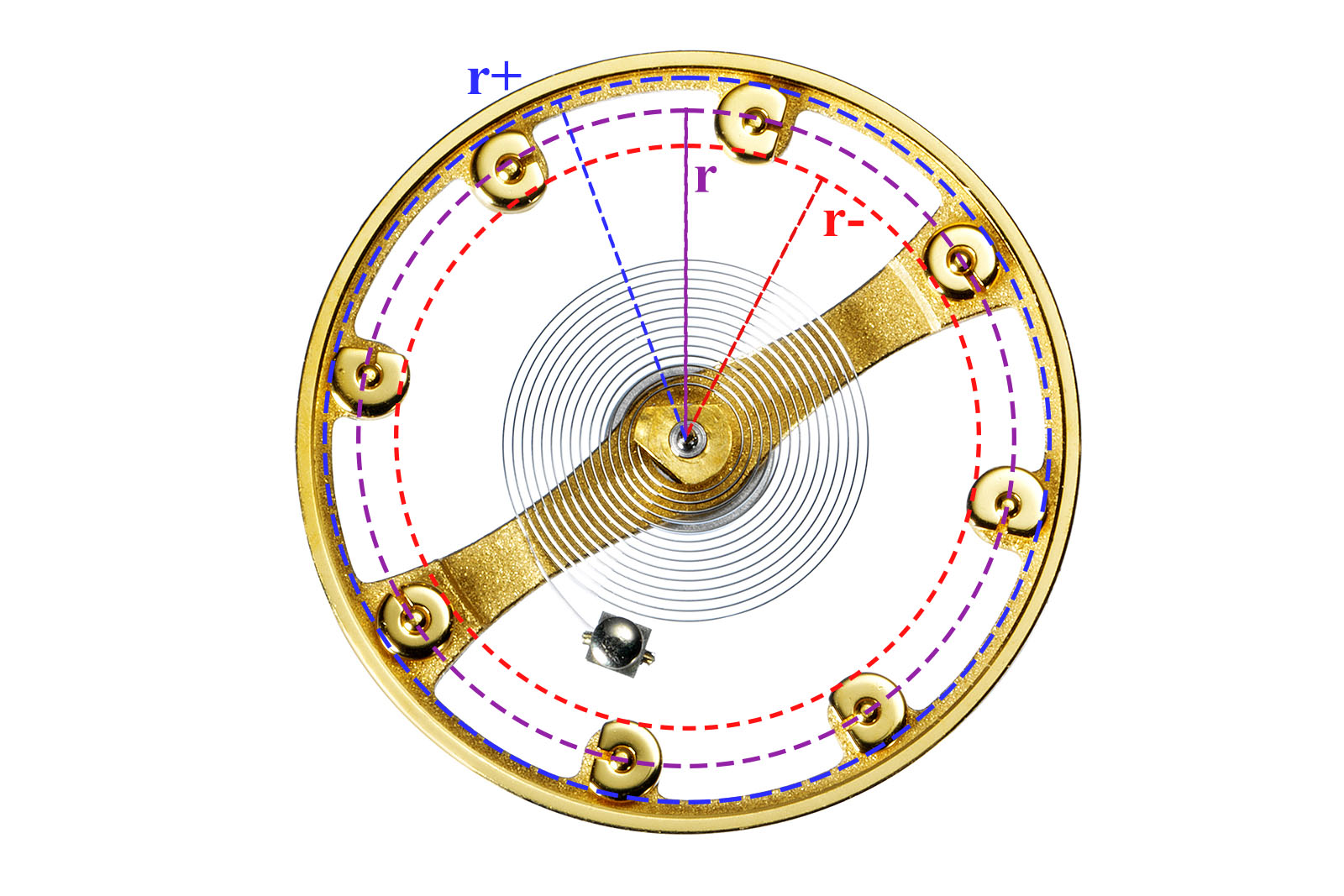

Figure 3. The C-shaped weights can slightly alter the radius where the balance mass is concentrated. It is important that the balance is well-poised at all times.

Figure 3 shows a Gyromax-style balance with inertia weights, or masselottes in French. The C-shaped weights are asymmetrical and carry more mass on one side. From a base r in purple, the watchmaker can carefully adjust the masses for the position r+ in blue or r- in red. For r+ the watch runs slower and for r- the watch runs faster, the balance having a shorter swing period.

The rim weights can be as well replaced by timing screws. Tightening the screws would reduce the gyration radius, while loosening them would increase the radius. Most marine chronometers relied on heavy, screwed balances. Sometimes inertia weights are preferred over screws because they keep the balance more aerodynamic, which reduces the air drag.

The F. P. Journe free-sprung balance with two pairs of regulating weights, for four in total

A free-sprung regulator is more difficult to produce than a pin regulator and requires a more expert hand for proper adjustment. Any slight imbalance between a pair of screws or weights can throw the balance out of poise, making for a faulty oscillator.

During regulation the watchmaker has to make sure any weight displacement is accounted for by a corresponding action on the opposing side. This ensures the balance is well poised.

Comparisons

While the two systems fulfil the same purpose, they differ very much. While each of them presents both advantages and disadvantages, the inertia weight regulation is clearly more advantageous overall.

Compared to inertia weights, the pin regulator is indeed easier to produce and to set, meaning it is objectively less costly for the manufacturer. The great issue with it is that the factory regulation can shift over time. A pin regulator is susceptible to move out of position, even fractionally, in case of mild shocks. Such small position shifts can, cumulatively, lead up to noticeable rate errors, even if the rest of the movement is running well.

A pin-regulated balance in the TAG Heuer CH80 chronograph movement; this particular arrangement is known as an Etachron regulator, widely employed in classic ETA calibers and known for its ease of setting though not for beauty

Moreover, the last coil of the hairspring has some play between the two pins, which was shown to cause isochronal defects if not adjusted properly.

On the other hand, the inertial weights system is costlier to produce and adjust, but assures the factory regulation holds for a long time. The weights or screws cannot be displaced by shocks, so they keep their exact position indefinitely, unless directly acted upon.

The two systems are similar to steel types used in knife making: some producers opt for common steels which can be sharpened fast, but also lose their edge fast, while other producers prefer performance steels which, although costlier, have a much greater edge retention.

The Habring2 A11 with a Triovis regulator, a more refined alternative to the simpler Etachron regulator

The demanding Poincon de Geneve criteria stipulates that an eligible movement needs to either have a free-sprung balance or a pin regulator with reliable means of keeping it locked.

Commonly this can be accomplished by either a Triovis regulator (pictured above), or a swan neck regulator (below). The Triovis system binds the pin regulator to the stud carrier with a screw and rack system, while a swan neck keeps the pin regulator locked under tension from an arched spring.

A chronometer-grade Patek Philippe pocket watch with a swan’s neck regulator: the curved spring keeps the pin regulator’s long arm locked against a screw, rendering it immobile. This is a very secure pin regulator which can reliably hold its regulation for a long time.

Relevance and use

Any mechanical watch relies on at least one of these two regulating systems. Some brands adopted free-sprung balances a long time ago, while others are only now making the shift.

For a long time now, Rolex has been using its proprietary Microstella system, which is a sort of free-sprung balance with timing nuts inside the rim, rather than timing screws. Patek Philippe has employed the patented Gyromax balance wheel since the 1950s.

A current Patek Philippe cal. 240 with a Gyromax balance wheel with only two pairs of timing weights.

Established independent watchmakers such as F.P. Journe or MB&F, along with more artisanal makers like Rexhep Rexhepi or Raul Pages opt for free-sprung balances, suggesting the system also turned into a de facto mark of prestige.

The signature raised balance wheel of the MB&F LM series, with four timing screws and an aerodynamic design.

The widespread implementation of silicon hairsprings has discreetly caused a shift towards a more mainstream use of free-sprung balances. This is because silicon hairsprings are usually moulded with a special end curve which improves the springs’ concentricity, but which doesn’t work all too well with traditional pin regulators. This has slowly led brands that embraced silicon springs to also use weighted or screwed balances.

Inside a Breguet tourbillon, a titanium balance with recessed screws. The balance emulates the angular, aerodynamic rim design made by Breguet himself and used by the likes of George Daniels or Derek Pratt.

A notable such example is the Swatch group. Current Breguet and Blancpain models mostly feature free-sprung balances with silicon hairsprings. Omega’s full catalogue of in-house movements relies of silicon hairsprings and screwed balances. Longines, Tissot and Hamilton timepieces also mostly feature a sort of weighted balance, paired with a silicon spring.

Comparatively, classic ETA movements (and their Sellita counterparts) employ almost exclusively an Etachron regulator, which is a variant of the pin regulator easy to manufacture and set on a large scale. This reflects the maker’s mass production approach. Surprisingly some high-end manufacturers like Cartier still rely heavily on pin regulators in their movements, which might be disappointing for some collectors.

An Etachron-type regulator in Cartier 1928 MC chronograph movement

The continuous advancement of production techniques and more discerning customers seem to have pushed the industry into slowly transitioning to free-sprung regulators. Breitling recently introduced a free-sprung variant of the B01 caliber, while high-grade movement producers like Vaucher or Kenissi exclusively deliver calibers with free-sprung balances.

Back to top.