In Depth: Petermann Bédat 1967 Deadbeat Seconds

Simply marvellous.

Formed only recently by two young watchmakers, Petermann Bédat’s very first timepiece is the 1967, a time-only wristwatch featuring an elaborate deadbeat seconds mechanism.

Unusually, the brand made its debut in a gradual manner, having shown its first prototype in 2018 before launching the final version of its debut watch earlier this year. Even more unusually, the successive iterations of the 1967 progressively improved, in both style and finish, to a point where the production version of the watch is simply marvellous.

Initial thoughts

When I saw a prototype of the 1967 last year, I didn’t think much of the design, but the movement was clearly well done, even in as a half-finished prototype.

Rather than massaging the earlier design into better shape, Petermann Bedat ditched it in favour of what you see here. Best described as a modern take on the fashionably retro “sector” dial, the dial looks good and also shows off the brilliant finishing.

The decoration visible on the front hints at the quality of work, and the movement visible from the back confirms it. In the smallest details the greatest finesse is visible, in the sharp points of the deadbeat seconds anchor or the escape wheel bridge below the balance.

Crucially, the watch pictured is a prototype – amongst other things, the hands are incorrect and the wheels for the deadbeat seconds mechanism are not perfectly finished – yet it is obvious the quality of execution is excellent.

Beyond its tangible qualities, the 1967 also appeals for blends elements new and old, a feat that few classically-inclined watches manage to do well. The dial, for instance, is a twist on the “sector” dial that smartly reveals the gorgeous keyless works. And the movement incorporates a deadbeat seconds mechanism designed in the 1940s by a teacher in a Swiss watchmaking school.

All of that comes in at a bit under 60,000 Swiss francs, or about US$66,000. It’s great value as such things go.

The 1967 prototype of 2019

That said, the watch is not perfect, but the niggles are minor. I would have preferred a thinner-looking case – making it actually thinner is not possible due to the movement height – and perhaps more stylised lines for the case design. A longer power reserve than its 36 hours would also be useful.

But the 1967 is tremendous watch, especially from a new brand founded by two watchmakers under 30. It’s proof that Messrs Petermann and Bédat, despite their youth, have both artisanal skill and a good eye. They know what they are doing, and what they do next will be worth watching.

The brand

Just three years old, the brand is named after its Gaël Petermann and Florian Bédat. Both just 28 years old, the pair met at watchmaking school in Geneva, and also at A. Lange & Söhne, where they spent some of their formative years. Both then spent a few years doing restoration and servicing; Mr Petermann, for instance, was often called upon to overhaul timepieces going on the block at Christie’s in Geneva.

Florian Bédat (left) and Gaël Petermann

In 2017 they joined forces, establishing Petermann Bédat in Renens, the town where Mr Petermann was already located. The choice of location was not accidental: their workshop sits beside the premises of Dominique Renaud, a cofounder of complications specialist Renaud & Papi who more recently set up his own brand (which has unfortunately gone bust). Mr Renaud helped construct the cal. 171 in the 1967, and in return the two watchmakers did work for Mr Renaud’s brand.

Evolution

Having been in development for several years, the 1967 has evolved considerably since an early prototype was shown in 2018. It has been artfully refined, both in terms of design and movement decoration, resulting in a watch that is considerably more appealing than its earlier iterations.

The evolution of the 1967 is itself notable, for independent watchmakers, like many artists, regard their creations as unrivalled in beauty and unsurpassed in inventiveness. So they rarely make substantial changes to designs, regardless of what anyone says.

The earliest prototype for the 1967 (left) and last year’s version

But the general reaction to the prior dial designs for the 1967 was mixed at best. Even last year’s version, which was fairly elaborate, lacked character and did not do justice to the movement, which was already impressive despite being a work in progress.

Fortunately, the pair revamped the dial design with the help of Nicolas Barth Nussbaumer, a longtime watch designer in Neuchâtel. The dial that’s now on the watch is an unusual mix of old and new, while also managing to show off a good deal of the under-dial finishing.

The movement in the 2019 prototype

Open “sector”

Although both the movement and dial of the 1967 have been refined a great deal, the case is largely identical to the original design. It’s unsurprisingly, since it is a simple but effective design.

Granted the case design is neither outstanding nor special, but it serves the purpose well. The lines of the case are clean and unfussy, giving it a low-key look that directs attention to the dial.

It is 39 mm in diameter, and 10.7 mm high – not thick but it feels so for two reasons. One is the relatively small diameter, and the other are the flattish bezel and back, which makes the case middle taller. But it still sits well on the wrist, feeling like a compact, high-quality watch, much like a Voutilainen Vingt-8 for instance.

In contrast to the case, the dial design is interesting, managing to blend classical design and mechanical elements in a coherent manner. It is clear sapphire topped with a central plate and minute-track ring, both made of steel. Printed hour markers on the sapphire form the “sector” layout, and also give the dial an appealing sense of depth.

Because the markers are thickly printed in glossy black lacquer, they cast noticeable shadows on the base plate below. At a steeper angle, the shadow cast by the central plate of the dial is also visible, which enhances the effect.

The dial design smartly allows the two watchmakers to show off decoration on the front without being excessive in styling. The standout detail is between one and four o’clock, where the levers of the keyless works are revealed.

Basically the mechanism that allows the crown to engage in two different positions to wind and set the movement, the keyless works are beautifully executed in form and decoration. All of the steel levers are black-polished and outlined with polished bevels on the edges. Even the tension spring has bevelled edges that continue as it narrows, with the bevelling ending only where the spring is impossibly thin.

Though not part of the movement, steel minute track and central plate are equally well finished. Both have a finely frosted top surface and wide, pronounced bevels that are mirror polished.

Beyond the finishing, the dial construction is also fairly complex, despite the straightforward design. The ring with the minute track is held in place with two screws that go through the sapphire disc and secure the ring to the base plate. And the central plate has four pins on its underside so it seats correctly on the sapphire disc, and is held in place with a bit of adhesive.

Calibre 171

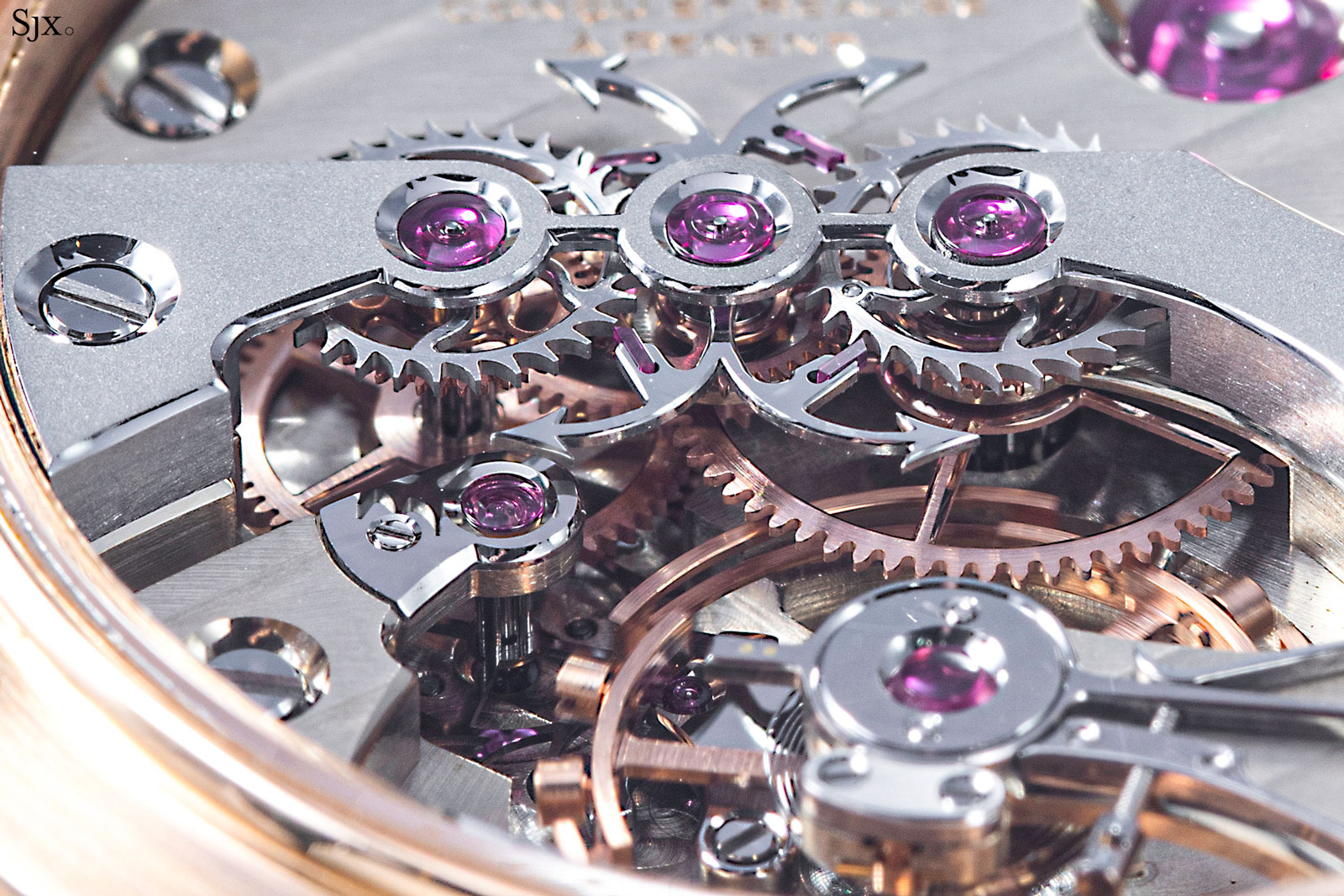

The key features of the movement in the 1967 are obvious as soon as you turn the watch over: a hand-wind movement with an elaborately constructed secondary escapement for the deadbeat seconds that’s mounted on the three-quarter plate.

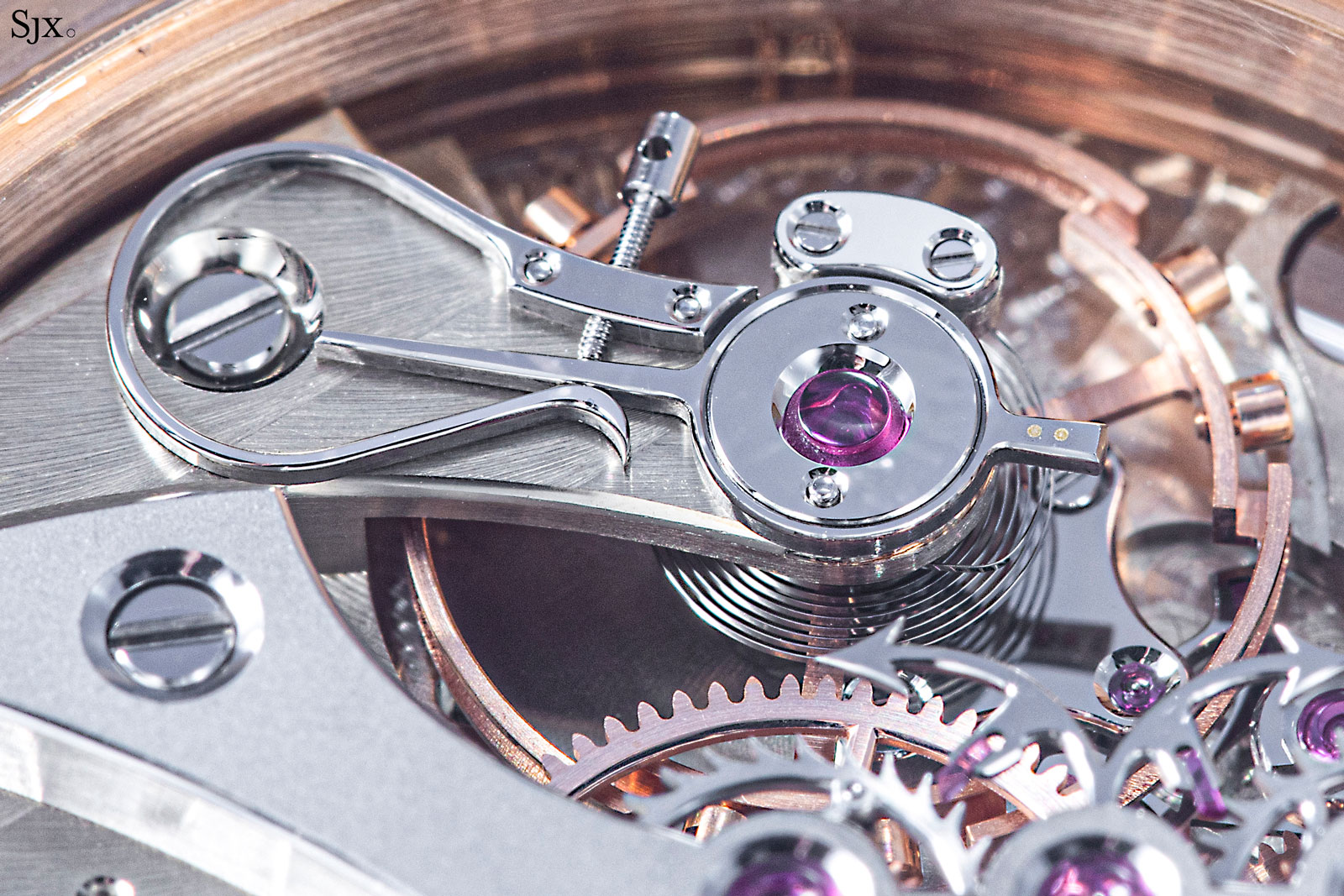

Because the deadbeat seconds escapement fairly high over the three-quarter plate, the movement has a degree of depth not usually seen in a time-only watch. That’s best appreciated up close, but it is impressive, particularly in how the polished components reflect on each other.

Note the reflection of the deadbeat seconds escape wheel on the polished steel cap of the escape wheel

Very much classical in style: the movement is equipped with an adjustable mass balance wheel of Petermann Bedat’s own design that has recessed timing screws, as well as a Breguet overcoil hairspring, and swan’s neck regulator index

The operation of the deadbeat seconds escapement is easy to grasp once observed. As outlined in our recent article on the deadbeat seconds complication, the jumping seconds in the 1967 relies on “a secondary escapement driven by the fourth wheel of the going train. At the centre of the secondary escapement is a four-armed anchor with four jewel pallets that converts the continuous motion of the gear train into the jumping of the seconds hand.”

The unusual Petermann Bédat escapement relies on a two-sided anchor (with four arms tipped with arrows) gently rocking back and forth as it locks and unlocks on each side: As the fourth wheel (extreme left) rotates, the ratchet wheel on the left rotates with it, sliding one pallet on the anchor out along the way. The oscillation of the anchor causes the opposing pair of pallets to lock and unlock the adjacent spring-loaded ratchet wheel sequentially, advancing the seconds hand in one-second steps. Video – Petermann Bédat

Defined by the four sharp arrowheads on the two-sided anchor, the deadbeat seconds mechanism has an intricate, old-school construction that brings to mind an earlier era of watchmaking – perhaps early 20th century or even 19th century. Unsurprisingly, that is where its origins lie: the mechanism is modelled on one invented by Robert Gafner, who taught at the La Chaux-de-Fonds watchmaking school in the 1940s.

Specifically, Petermann Bedat based their movement on a 1949 pocket watch built by Rene Fesselet, a student at the school (who was presumably a student of Gafner). The pocket watch was equipped with a tourbillon, remontoir d’egalite constant force mechanism, and a deadbeat seconds driven by the Gafner mechanism. Clearly conceived as a top-of-the-line precision timekeeper, the 1949 pocket watch was given a deadbeat seconds for an obvious reason: the ability to read and set the seconds hand exactly.

In the 1967, on the other hand, the deadbeat seconds operates in isolation; it is the only complication in the movement. That perhaps is the only weakness of the watch from a conceptual perspective. For one, the jumping seconds is for visual effect rather than working in tandem with a remontoir for instance. At the same time, the jumping seconds is a drag on performance as it consumes a substantial amount of energy from the mainspring, explaining the short, 36-hour power reserve.

But its shortcomings are easily forgiven because the movement is outstanding in design and decoration. As the components visible through the dial already imply, the movement finishing is exemplary. The most obvious example of the excellent finishing is the deadbeat seconds mechanism. It’s held in place by a wide bridge with a frosted top and anglage that naturally incorporates several sharp, inward corners.

Especially noteworthy is the four-armed steel anchor, which is black polished and expertly bevelled, even to the points of each arrow

The steel parts that make up the regulator index are also black polished and bevelled on their edges, even the lateral screw

The three-quarter plate is covered in Geneva stripes, with all of the screws and jewels in polished, bowl-shaped countersinks; the large jewel for the barrel sits in an appropriately wide countersink

Even the tiniest pins sit in countersunk holes, and the slot for the winding click also has bevelled edges

Concluding thoughts

In the category of time-only watches by independent watchmakers, the 1967 is amongst the best, most obviously in its finish and quality, but also its design.

A couple of things can be improved, most prominently the case, but none of the potential improvements are crucial to the appeal of the watch. It is a winner, particularly in light of its more-than-fair price.

Key facts and price

Petermann Bédat 1967

Case diameter: 39 mm

Case height: 10.7 mm

Material: 18k white or rose gold

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: Cal. 171

Functions: Hours, minutes, and jumping seconds

Frequency: 18,000 beats per hour (2.5 Hz)

Winding: Hand-wound

Power reserve: 36 hours

Strap: Alligator with pin buckle

Limited edition: 10 pieces in each case material

Availability: Direct from Petermann Bedat

Price: 59,800 Swiss francs

For more, visit Petermann-bedat.ch.

Back to top.