In-Depth: Cambodia’s First Watchmaking School

A first-rate education in Phnom Penh.

When I first got wind of the newly-opened watchmaking school in Cambodia, I was surprised. And when I found out the school was a world-class institution fully equipped with brand-new, top-of-the-line equipment and staffed by veteran instructors from Switzerland, with local students studying for free – I was sceptical.

I am ashamed to admit, I was wrong. There is a world-class watchmaking school in Phnom Penh, one with ambitions that go well beyond merely training technicians to overhaul watches. Freshly set up and filled with the very best equipment – including brand-new, full-spec Schaublin lathes and the latest Leica microscopes – the Prince Horology Vocational Training Center is a no-expense-spared project that’s likely the most impressive watchmaking academy outside of Switzerland.

And another classroom, with the micro-mechanics machine shop at the back

Backed by a local real estate conglomerate, the school will conduct a two-year programme similar to the de facto industry standard, the 3,000-hour course offered by Swiss academy WOSTEP (short for Watchmakers of Switzerland Training and Educational Program).

Both theoretical and practical, the school’s syllabus encompasses the theoretical, for instance lessons on the history and culture of watchmaking, as well as benchwork, including machining, micro-mechanics, and production of components like the winding stem and balance staff. At the same time, because the school is the brainchild of timepiece collectors who value artisanal watchmaking, it will also emphasise traditional, artisanal skills, like decoration and turning.

Presses to remove screw-down and snap case backs

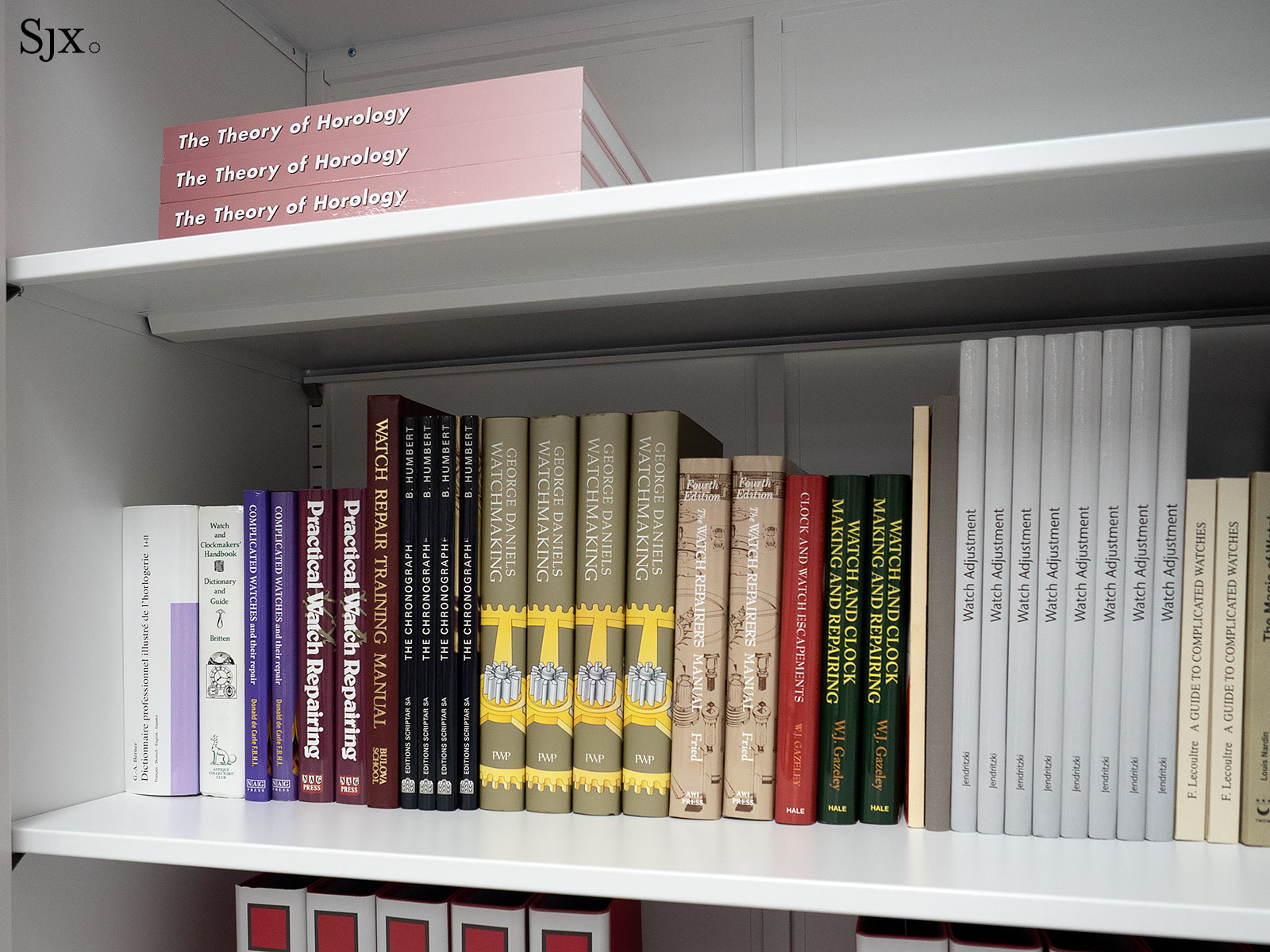

The library, which naturally includes the famous Watchmaking by George Daniels

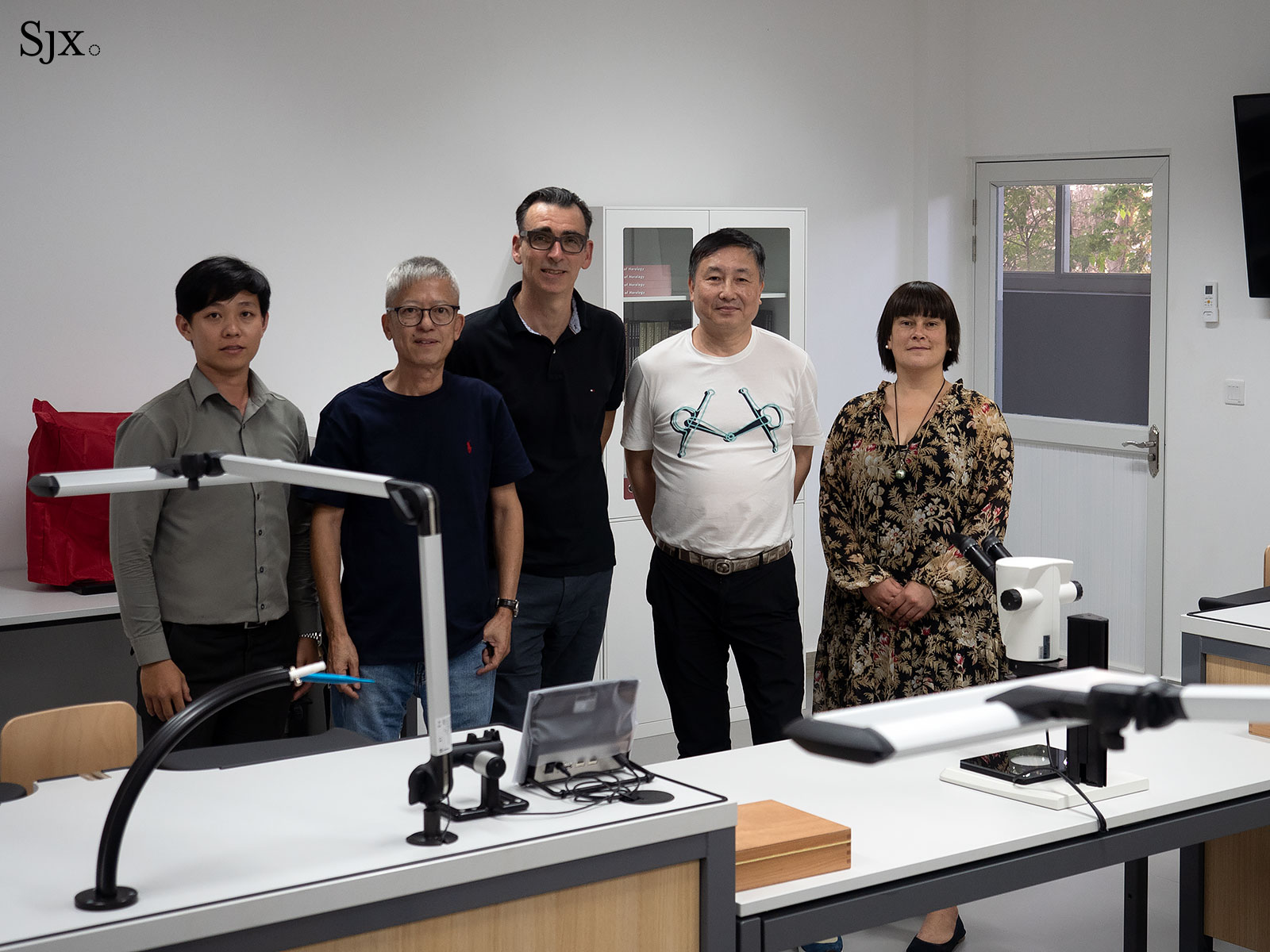

The team behind the school

Now in its third round of admissions interviews and tests, the school will start its term in early June 2020 (though the COVID-19 coronavirus might delay that), with the inaugural class of eight students graduating in 2022, becoming the first watchmakers in Cambodia trained in their native country.

An ancient kingdom of artisans

Bordered by Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos, Cambodia is one of Southeast’s Asia poorer countries, with a gross domestic product per capita (at purchasing power parity) just one quarter of Thailand’s. The country’s privation can be traced back to the Khmer Rouge, in power for a brief but disastrous three years until 1979, setting back the nation’s development by decades. The regime wiped out a quarter of the country’s population, with an emphasis on ridding the country of its educated class, in an attempt to turn back the clock and return Cambodia to a pre-industrial agricultural society.

The current prime minister of Cambodia, Hun Sen, took office in 1985 and has been in power since, making him the longest-serving, non-royal ruler in Asia. While sometime criticised for his authoritarian tendencies, his rule has brought cultivated political stability, which in turn has led to rapid economic growth, averaging almost 8% a year since 1998, making Cambodia one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

One driver behind the turbocharged growth in recent years has been China, which accounted for over 40% of the country’s foreign-direct investment in 2019, especially after Cambodia became a key part of Belt and Road Initiative. As it happens, the school was made possible, in part, because of Chinese investment in Cambodia.

The school is funded by the charitable arm of Prince Real Estate Group, a conglomerate founded by Chinese entrepreneurs. Founded only in 2015, the Prince group has swiftly become one of the largest companies in Cambodia, with a real estate portfolio worth some US$2 billion.

The Prince group has completed, or is close to completing, some one million square metres of commercial and residential space – with another 20 million square metres in the works. It has also expanded into hotels, supermarkets, farming, and in 2017, the group set up the country’s newest airline, Cambodia Airways.

The ground floor atrium of the Prince group headquarters, with Dragon-Riding Buddha by Taiwanese sculptor Li Chen at its centre

And now the Prince group is not only bankrolling the school’s establishment, but also covering its operating costs and importantly, funding scholarships. Even though school fees are notably low – for locals it’s only US$2,500 for two years, while the comparable programme at WOSTEP costs about US$36,000 – most local students will receive full scholarships that also cover accommodation and living expenses.

The origins of the school lie with several individuals in Prince group’s senior management who love watches, and decided that watchmaking would be an unconventional yet practical way of doing good. Notwithstanding its recent streak of high growth, Cambodia remains underdeveloped in several aspects, including suffering from a lack of technical or vocational schools, a gap the watch school aims to fill.

The formal reception room inside the Prince group building, lined with the flags of Cambodia and China

For cultural and historical reasons, the people of Cambodia are well suited to watchmaking, despite it being a completely new vocation. The country has a rich history of woodworking and stone carving – exemplified by the magnificent treasures in the ancient city of Angkor built by the Khmer Empire.

While Cambodia’s recent, tragic history also means its people value objects and repair them. Anything that can be salvaged is fixed and reused, rather than discarded. Evidence is found along the streets of Phnom Penh, which are filled with workshops selling second-hand car and truck engines.

The place of learning

Already in its final stages of setup during my visit in late February, the school is in the Chrouy Changvar district of eastern Phnom Penh, housed in a nondescript building just a few streets away the Mekong River. Despite being tucked away a distance from the main road, the school is incongruous, sitting in an area mostly filled with a mishmash of stores, backpacker hotels, and even an international school.

While unassuming on the outside, the school’s lobby makes it obvious the building is special. Lining the corridor are photographs of Prince group management with the Prime minister and other government officials, illustrating the Cambodian government’s support for the school.

As a visitor, stepping into the school is surreal: a stark transition from the chaotic streets of Phnom Penh into clean, cool, and quiet classrooms filled with the best tools. Though the school is a charitable project, but it is decidedly not a cut-rate operation – in fact, it is the exact opposite, expensively kitted out to full spec.

A tool for balance wheel poising, brand-new in box

A set of digital measuring tools – callipers (above) and micrometer

Through the Leica glass

“The school was conceived with the deepest respect to the Cambodian people,” explains school advisor Jessica Thakur. “When setting up the school, the Prince group was determined to offer the highest quality in all respects to the students – with no exceptions – who will be completely immersed and indoctrinated in the Swiss watchmaking culture.”

The sheer commitment to giving students a Swiss watchmaking education is admirable and even a bit peculiar. Practically everything – everything – is imported from Switzerland, right down to the coffee, chocolates, and even the lockers for the students. The school is as good as any school in Switzerland – the equipment and tools are identical – but perhaps even better because everything is new and shiny, with a fresh metallic scent.

Fuel for watchmakers

Yes, they are Swiss made too

3,400 hours

The school’s two-year programme has been designed according to the certificate fédéral de capacité (CFC), standards for vocational training defined by the Swiss government that are widely considered the industry norm for basic watchmaking education. The well-known and highly-regarded 3,000-hour programme at WOSTEP is based on the same CFC benchmarks.

Around four-fifths of the 3,400-hour curriculum is dedicated to a broad range of practical work, amongst other things milling, turning, burnishing, gear cutting, heat treatment for hardening and tempering steel, decoration and hand finishing, as well as regulation. Case and bracelet refinishing, done at the school’s fully-equipped polishing workshop, form another key part of the practical coursework.

Presses for hand-setting

At the same time, the course is also sensitive to the needs of its students, and aims to impart skills that will enable graduates to make a living as watchmakers. To that end, the course covers the servicing and repair of mechanical as well as quartz watches, up to the complexity of an automatic chronograph with calendar (an ETA Valjoux 7750 movement, in other words). Such work includes the obvious, like inspection, disassembly, and lubrication, but also higher-level skills like adjusting and fabricating components.

All that culminates in a final-year project, where each student will be expected to produce, adjust, and hand-finish a school watch.

A press for a snap-on case back, with an assortment of nylon dies for different back sizes

An all-important bit of kit in a humid, tropical country – an industrial-strength dehumidifier

Old-school techniques

While artisanal watchmaking skills are sometimes regarded as unimportant commercially, they are crucial in preserving the tradition of haute horlogerie, one of the school’s founding principles. In that sense, the school is actually going against the grain.

“We are seeing a trend in the industry of focusing on watchmaking education limited to technician-style training, with little-to-no focus on artisanal watchmaking or advanced subjects,” notes Ms Thakur. “The programme in Cambodia will be one of the few of its kind outside of Switzerland that covers micro-mechanics, decoration, and full adjustment of mechanical movements,” continues Ms Thakur, “Some schools are no longer able to offer such comprehensive training, mostly due the sheer investment needed.”

Assorted gauges

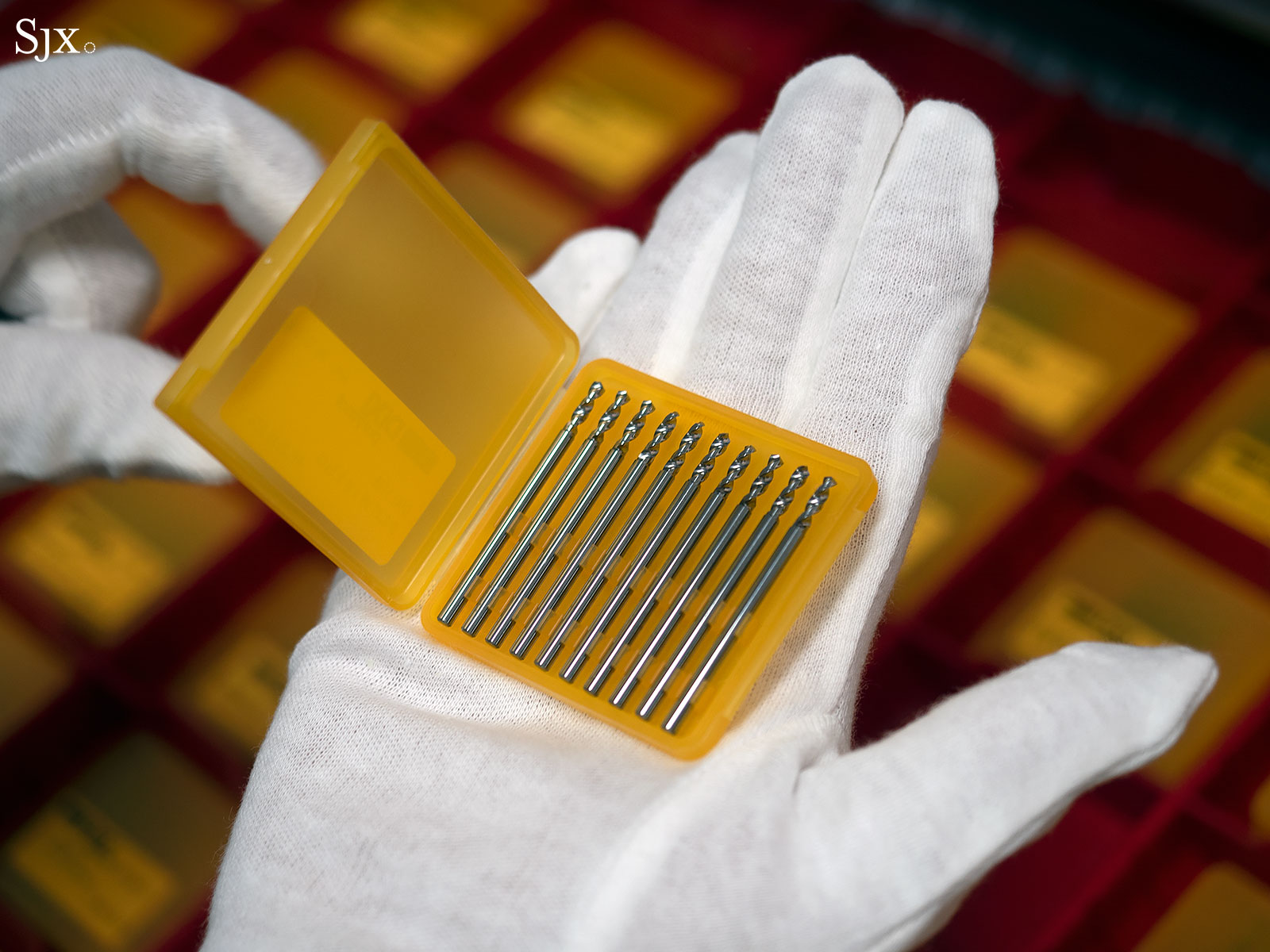

Pristine drill bits

Digital micrometers

A lathe for rounding and polishing pivots

Part of a staking set, a versatile tool often used to press jewels into plates

That investment is on show throughout the school, which has been outfitted with every tool and instrument imaginable: from George Daniels’ Watchmaking to bars and plates of varied metals for making parts, as well as an impressive selection of machines bearing names familiar to anyone who has visited a Swiss watch factory, including Elma, Witschi, and Bergeon, as well as more esoteric brands that will be known only to specialists, like Marcel Aubert, Dixi, and Borel.

Perhaps most impressive is the micro-mechanics machine shop that’s stocked with a Fehlmann Picomax 20 milling machine, a pair of Schaublin 70 Mi-CF lathes, and a much-coveted Hauser M1 jig borer.

More hardware is found one floor above the machine shop, where the workshop for case and bracelet finishing is located. It boasts two Crevoisier C5100 polishing stations accompanied by a pair of C501 machines for lapping and satin-finishing.

The machine shop

The milling machine

The flexible blue nozzle delivers lubricant to the workpiece

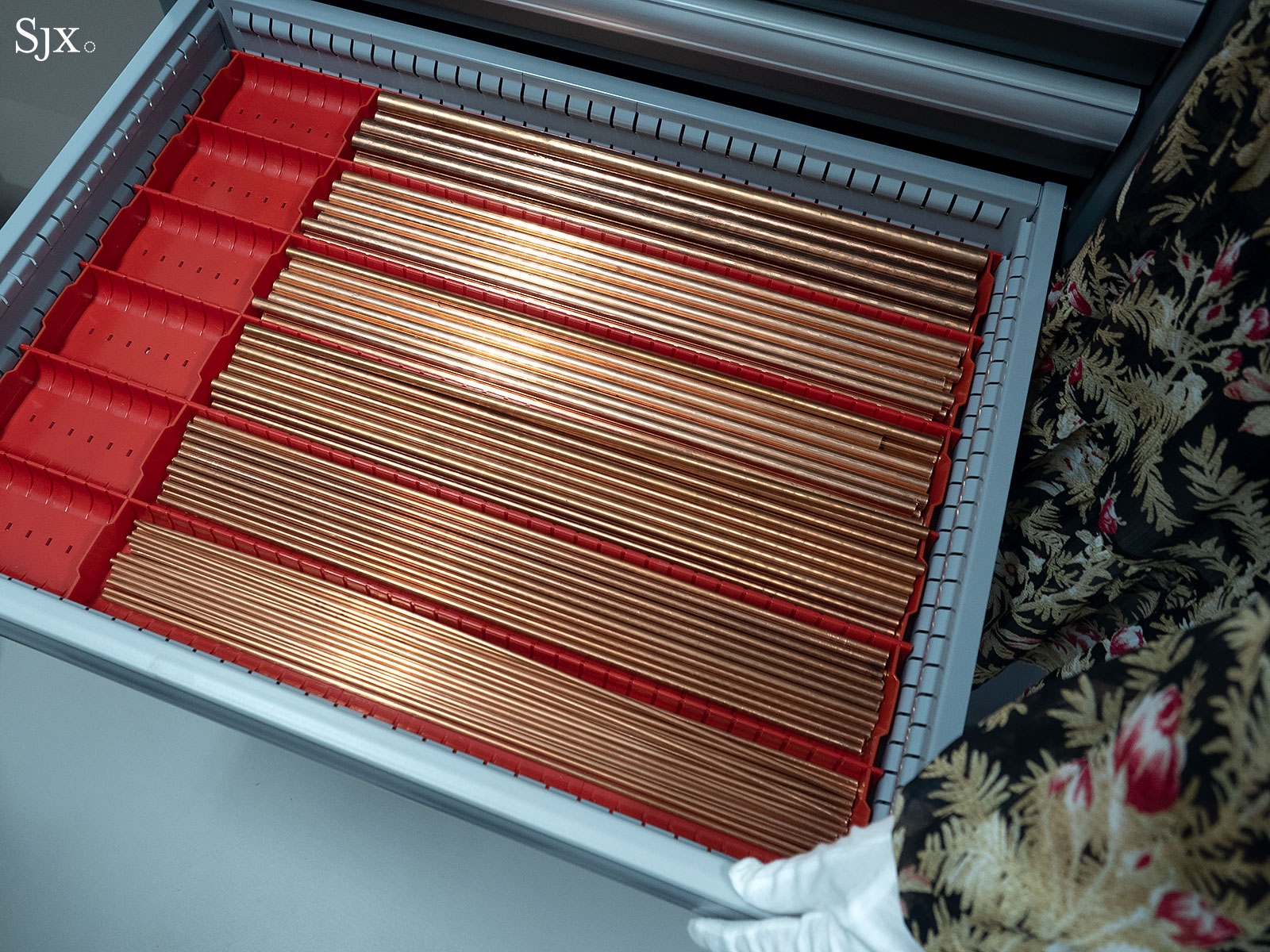

Copper bars of assorted diameters

Rods of brass, copper, steel, fibreglass, and resin

Installation of the Crevoisier polishing machine

Put simply, students are provided everything necessary to produce, finish, and repair a watch, a feat made possible only with the substantial investment by the Prince group. Though the total cost of the school is a secret, a fully-equipped Schaublin lathe alone retails for about US$45,000, implying the a six- or even seven-figure total.

While much of the equipment and tools are routine for a watchmaking facility, the newness of everything was a strange sight, even for me. And the equipment should remain that way, even after classes begin. Ms Thakur points out the curriculum includes segments on maintenance of the tools and equipment, which aim to cultivate a respect for the tools of the trade, a key quality of a watchmaker.

Reverence for one’s tools also mean that students will be responsible for the tidiness the workshops, ranging from the shared equipment to each’s pupil’s personal bench. The benches, incidentally, are all produced by the horological-workstation maker Allemand Frères. The Swiss specialist is responsible for all of the workstations in the school, ranging from the sturdy micro-mechanics benches to the electronically-adjustable watchmaker’s benches.

The height-adjustable bench with its full assortment of tools

Imparting knowledge

Like the school’s hardware, its educators are also imported from Switzerland.

The chief instructor is Anthony McGonigle, who most recently had his own workshop in Rome restoring vintage timepieces. Now a full-time resident of Phnom Penh, Mr McGonigle is better known to watch aficionados as the brother of John and Stephen McGonigle, the independent watchmakers behind the eponymous brand.

Anthony McGonigle

Mr McGonigle will be assisted by the husband-and-wife team of Maarten Pieters and Ms Thakur, both of whom now live part-time in Phnom Penh. The director of WOSTEP for over 16 years, until 2018, Mr Pieters arrived at WOSTEP from Omega, where he worked in Haute de Gamme department responsible for the brand’s most complex watches, most notably the De Ville Central Tourbillon. Before that, he worked at Janvier, the prototyping and restoration outfit founded by Vianney Halter and Nicolas Court, and then THA, the well-known complications specialist once led by Francois-Paul Journe.

On the other hand, Ms Thakur started her career a long way from Switzerland, learning watchmaking in her home country of Australia before embarking on a career as a teacher, first at the watchmaking school in Texas sponsored by Swiss luxury group Richemont, followed by several years at WOSTEP.

Maarten Pieters

Perhaps as important as the academics are the gentlemen behind the scenes who keep the school running. The school’s executive principal is Sack-Man Loui, a retired entrepreneur who once ran an electronics factory in China. He’s been a watch collector for some 30 years, as well as a self-taught watchmaker. Mr Loui’s deputy is Penh Song Chhun, a native of Phnom Penh who manages the nuts and bolts of the school’s operations.

And the man responsible for putting all the pieces together in the first place is Xu Zhou, a mechanical engineer who learnt watchmaking by experimenting on his own timepieces. Now an advisor to the school, Mr Xu is well acquainted with the leaders of the Prince group, while also having extensive relationships across the watch industry as a long-time watch collector – it was his connections that got the school started.

From left: Penh Song Chhun, Sack-Man Loui, Maarten Pieters, Xu Zhou, and Jessica Thakur

Skills for a lifetime

After spending two afternoons at the school, I visited the headquarters of the Prince Real Estate Group, a five-story glass hexagon that’s located on the southern end of Koh Pich. A strip of reclaimed land on the Mekong River, Koh Pich translates as “Diamond Island” and encapsulates the rapid, and sometimes garish, development of Phnom Penh. The district is a blend of Las Vegas and Dubai that’s home to enormous residential and commercial developments in ornate, neoclassical style, along with replica of the Arc de Triomphe, and thoroughfares like Elite Road and Harvard Street.

With operations paused as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Prince building was quiet, while in ordinary times it would have been thronging with Chinese buyers of apartments. At the time of my visit in February, the group’s business had already been on hold for almost three months, according to the company’s executive chairman, Qiu Guoxing (who was wearing a Patek Philippe ref. 5961P that day).

Some 80% of building materials, from nails to concrete, are imported from China, as are almost all the workers. Business will eventually get back to normal, said Mr Qiu, but it would probably be gradual, requiring months to restart operations and perhaps a year or more to get back up to full speed.

Nonetheless, the COVID-19 pandemic is just a speed bump, continued Mr Qiu, who was unmistakably upbeat about the future of Cambodia. As long the country enjoys political stability, and preserves the openness of its financial system, explained Mr Qiu, Cambodia will be one of the great economic success stories of the coming decade.

Qiu Guoxing, Executive Chairman of the Prince Real Estate Group (left); and Xu Zhou, advisor to the Prince watch school

That prosperity will ensure the success and longevity of the school, which will likely evolve over time as the country develops. For now, the school will produce watchmakers who will work overseas. Cambodia today has little demand for skilled watch repairers, though that is changing with the rapid accumulation of wealth in the country. According to Ms Thakur, several watch brands have already expressed interest in potentially hiring graduates to staff their service centres in Asia.

At the same time, talent is also flowing in the other direction, slowly but surely, as the school piques the interest of would-be watchmakers on the other side of the world. “We have even bench-tested European candidates who wish to follow the programme,” notes Ms Thakur, “which demonstrates the confidence that the school has already gained internationally.”

And over the longer term, the school aims to plant the seed of a watchmaking culture in Cambodia, and in a modern and novel manner revive the artisanal leanings of the ancient Khmer Empire.

Back to top.