Complicated Collectors: Cecil Clutton

The rational collector who befriended George Daniels.

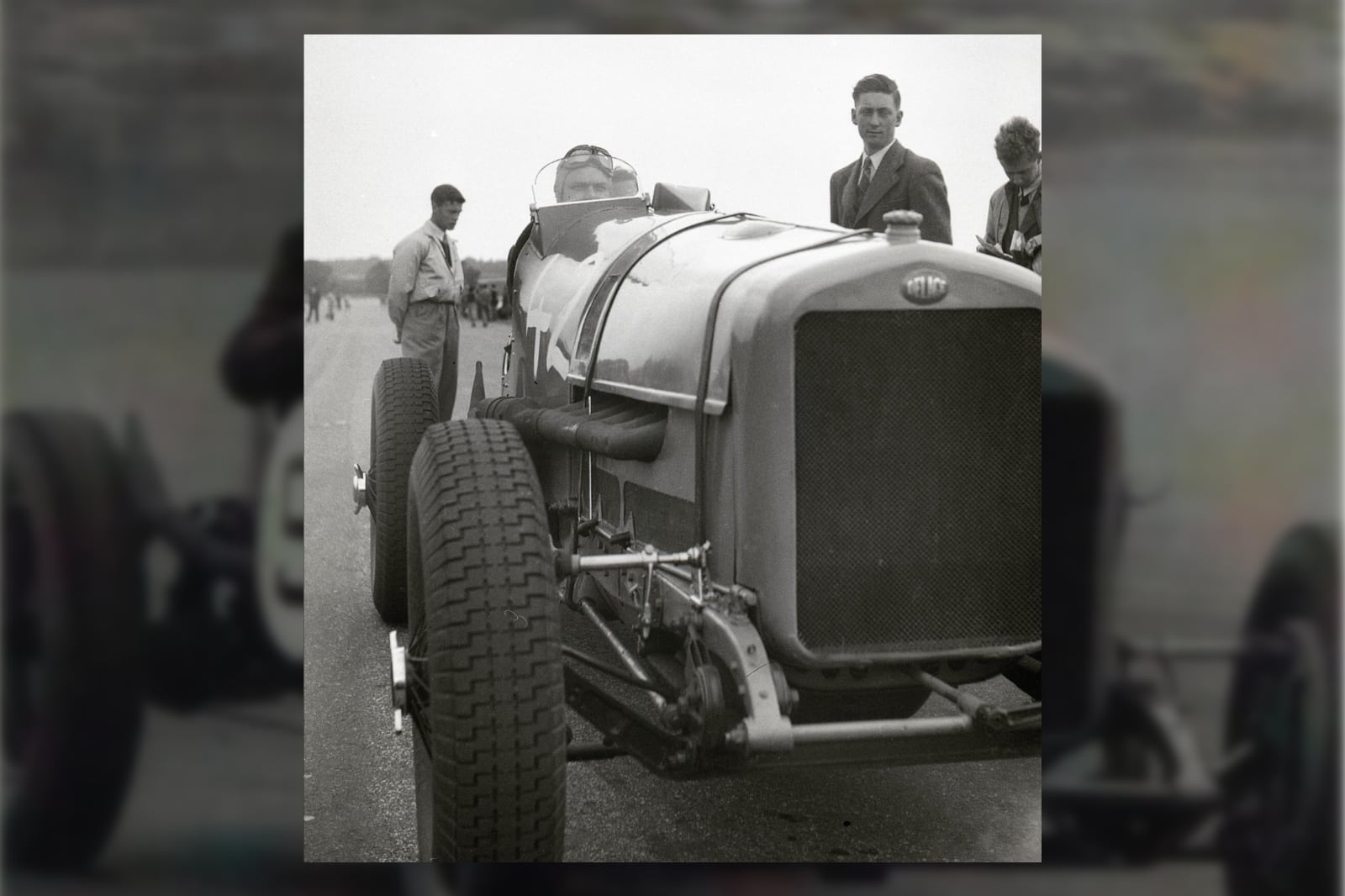

The 1908 Itala came alive on the Silverstone grid with a sound like controlled thunder. Cecil Clutton, known to his friends as Sam, settled into the bucket seat, his hands finding their positions on the massive steering wheel. He was 63 years old; the car was a year older. Around them, sleeker machines like the Bugatti Type 35 and ERAs growled in anticipation. The other drivers wore modern racing kits; Clutton wore a tie.

He dropped the clutch. The 12-litre engine roared as the rear wheels bit into the tarmac. Through Copse Corner, the car drifted wide, and Clutton held the line by feel; the steering wheel transmitted every message from the road surface through his palms. With Clutton at the wheel, the Itala crossed the line in third place; eminently respectable for a car that predated the First World War by six years.

But Clutton was no ordinary racing driver, having been appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for work rendered to the Crown Estate; his family founded the real estate firm Cluttons in the late 18th century. The CBE acknowledged his professional achievements in surveying, but by then his influence extended far beyond property management.

He had already served as President of the Vintage Sports-Car Club from 1954 to 1957, published foundational texts on vintage motoring, established himself as a leading voice in the British Organ Reform Movement, and begun building what would become recognised as one of Britain’s finest collections of precision watches.

Cecil Clutton sitting at the wheel of the Itala. Image – SJX composite/Bonhams

Purpose through use

It takes a certain type of person to race an antique car, but it’s what Clutton did after the race that best illustrates his outlook: he drove the car home. While other drivers loaded their precious machines on trailers, Clutton drove the Itala some 60 miles on public roads, threading through Northamptonshire villages where children stopped to stare at the mechanical monster clattering past their homes. The trailer sat empty in his garage, as it always did.

He could have loaded the car to preserve its mechanics from the wear and tear of ordinary driving, but the choice to drive it home represented a conviction he’d spent decades developing: a racing car existed to race, and the miles between garage and circuit formed part of that existence.

The Itala accumulated 60,000 miles over 56 years under his ownership. Clutton repaired what broke, sourced parts, and fabricated components when necessary. This maintenance was more effective at preservation than museum storage. By using the Itala as its designers intended, he kept alive the knowledge required to operate and repair such machines.

This conviction had shaped three distinct fields over the course of forty years. By 1972, Clutton had defined what “vintage” meant in motoring, disrupted British organ building through his Reform Movement advocacy, and redirected horological collecting toward precision rather than decoration. His influence rested on the simple principle that machines achieved their purpose through use, and preservation meant maintaining function across generations.

A meeting of minds

Clutton’s obsession with usage and preservation emerged gradually from his professional training and wartime experience. But its most consequential application had begun twelve years earlier, in 1960, at another race meeting where Clutton had noticed a Bentley he didn’t recognise.

The Bentley showed quality restoration work, mechanical soundness visible in how it sat, in the condition of its brightwork, and in details that separated competent rebuilding from mere assembly of parts. Someone had invested serious skill in restoring the machine to this standard.

Clutton, then 51 and having recently concluded his term as President of the Vintage Sports-Car Club, approached the owner. The man was younger, perhaps in his 30s, and introduced himself as George Daniels. They discussed the Bentley’s mechanical features and the challenges of sourcing period-correct components. The conversation revealed that Daniels had rebuilt the car himself, teaching himself the necessary skills after purchasing a wreck he couldn’t afford to have professionally restored.

The conversation turned to horology, with Daniels noting that he restored watches for a living. Clutton was a serious collector and had been a founding member of the Antiquarian Horological Society, established in 1953. He had also been recently appointed editor of Antiquarian Horology, and had assembled what was becoming recognised as one of Britain’s finest collections of precision-period timepieces.

Daniels would later describe Clutton’s demeanour during this initial exchange as “stiff and formally detached,” noting that his voice sounded as if he spoke “with a mouth full of cut glass”. That particular upper-class British accent carried both authority and social distance. Daniels immediately sensed he was “being probed”, tested to see if he merited continued conversation. Clutton possessed what Daniels called a “low boredom threshold.”

When Daniels demonstrated genuine knowledge by discussing escapement geometry, temperature compensation, and the technical differences between makers such as John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw, Clutton’s tone shifted dramatically to one of warmth.

A visionary patron

Clutton invited Daniels to his home in Blackheath in southeast London, marking the beginning of a friendship that would last three decades. More significantly, it initiated a collaboration that would produce two watches considered among the finest achievements of 20th-century horology.

The first, completed in 1969, proved that a single individual could still master all 30 trades required to build a complete watch by hand. The second, finished in 1976, incorporated Daniels’ revolutionary Independent Double-Wheel Escapement, a watch Clutton would wear daily for 15 years before bequeathing it to the British Museum.

But in 1960, these achievements lay in the future. What Clutton recognised at the race meeting was talent requiring cultivation, a self-taught craftsman with the discipline to rebuild a vintage Bentley from wreckage and the knowledge to discuss precision horology with authority.

Clutton had spent three decades building expertise and influence across multiple fields, and understood that preserving mechanical heritage required finding and supporting craftsmen capable of maintaining that heritage through practice rather than theory.

The paddock conversation represented Clutton’s philosophy in action: identify quality, support its development, and ensure the knowledge transfers to the next generation. The same principle that led him to race the Itala rather than store it led him to mentor Daniels rather than simply admire his work from a distance.

To understand why this meeting mattered, why Clutton possessed the knowledge, resources, and social position to transform Daniels’ career, requires understanding the foundations he’d built over the preceding five decades, beginning with his entry into the family profession in 1927.

The man from Blackheath

Cecil Clutton was born on September 16, 1909, into a family whose professional identity had been established for nearly a century and a half. The firm of Cluttons, chartered surveyors and land agents, had been founded in 1765 and, by the early 20th century had woven itself into the fabric of the British establishment. The firm managed vast holdings for the Church Commissioners and the Crown, maintaining estates that had outlasted generations of managers and would outlast generations more.

John Clutton had served as the inaugural president of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors in 1868, helping establish the professional standards that separated legitimate surveyors from speculators. The younger Clutton inherited this tradition of rigour. The surveyor’s role involved managing assets across decades, sometimes centuries, balancing present use against future preservation, ensuring that productive employment sustained rather than consumed the resource.

The long-term perspective required to manage properties in perpetuity would later inform Clutton’s approach to mechanical objects. The stewardship mindset he developed professionally transferred seamlessly to vintage cars and precision watches: you maintained these objects not for yourself alone but for future generations, accepting the role of temporary custodian rather than final owner.

Early years

His education began at King’s School, Worcester, where he studied from 1923 to 1927. The school’s proximity to Worcester Cathedral gave Clutton access to Edgar Day, who taught organ. Day allowed the young Clutton to practice on the cathedral’s instrument, introducing him to the unique relationship between the organ’s mechanism and architecture of the building around it.

By October 1929, barely two years after leaving King’s School, Clutton was studying organ construction with intensity. This early engagement with mechanical systems, understanding how voicing affected tone, how wind pressure influenced pipe speech, and how tracker action transmitted the organist’s touch to the pallet, planted seeds that would flourish across his later work in all three of his chosen fields.

The firm of Cluttons in London. Image – SJX composite/Cluttons

He joined Cluttons in 1927, immediately after completing his education. The firm provided more than employment, giving him financial independence, social standing, and access to elite circles. As he rose through the firm to become senior partner, and later appointed as Agent to the Crown Estate Commissioners, his professional competence in one field lent authority to his interventions in others.

The Second World War interrupted his surveying career. Clutton served as a pilot in the Royal Air Force, flying aircraft that demanded an intimate understanding of mechanical reliability. Little is known about his combat service, but the aviation experience proved foundational. He continued flying a de Havilland Tiger Moth privately until 1973 and maintained his relationship with aircraft for nearly three decades after the war ended.

A singular personality

After the war, Clutton returned to the family firm and established himself in Blackheath, where he would live for the rest of his life. He devoted his considerable resources and time to his professional duties and his consuming passions. His approach to life shaped his social arrangements in ways that became legendary among those who knew him.

Clutton famously possessed exactly six of each utensil: six plates, six forks, six knives, six glasses. This strict limit meant dinner parties remained small by necessity, ensuring conversations stayed intimate and focused. His approach to hospitality reflected his priorities: he used a cold marble table that cooled the plates, encouraging guests to eat quickly and return to the drawing room, which he considered “the proper place for talking.”

Contemporaries described him as possessing a “haughty manner” and an “ego-deflating wit” that he would “liberally unleash on anyone who bored him.” He maintained a “no-nonsense outlook” and was occasionally viewed as “self-opinionated.” Yet this sharpness coexisted with what Daniels called “mild and amusing eccentricity” and genuine generosity toward those who demonstrated serious interest.

The force of personality proved essential to his influence. Redefining the vintage car category over vocal opposition required confidence. Convincing church committees to abandon familiar Victorian organ sounds in favour of untested Baroque voicing required authority. Redirecting watch collecting from decorative arts toward technical precision required a sustained argument backed by deep knowledge. A more diffident man could not have achieved these transformations.

The Blackheath house became known to those in all three of his fields; vintage motorists, organ builders, and horologists visited to examine his collections, discuss technical problems, and benefit from his knowledge. The establishment, with its strict limit of six place settings and its cold marble table, became a salon where mechanical expertise and historical knowledge were exchanged across disciplines.

George Daniels 1932 Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 Long Chassis Touring Spider, parked alongside the ex-Cecil Clutton Itala. Image – SJX composite/Bonhams

By the time he met George Daniels in 1960, Clutton had assembled all the elements that would make their collaboration possible: professional success providing financial resources, deep technical knowledge across multiple mechanical fields, social connections to elite collectors and institutions, and a philosophy of preservation through active use that would find its ultimate expression in the watches Daniels would create for him.

The foundations were complete. What remained was to understand how Clutton had built his influence in each of his three chosen fields, beginning with the world that had first claimed him: vintage motoring.

The man who defined an era

The Vintage Sports-Car Club was founded in 1934 by enthusiasts who felt alienated by modern cars. The automobiles of the 1930s, increasingly standardised, mass-produced and equipped with synchromesh gearboxes, seemed to have lost something essential. Clutton joined as a founding member. But almost as soon as the club was founded, it became consumed by the question of what, exactly, qualified as “vintage”?

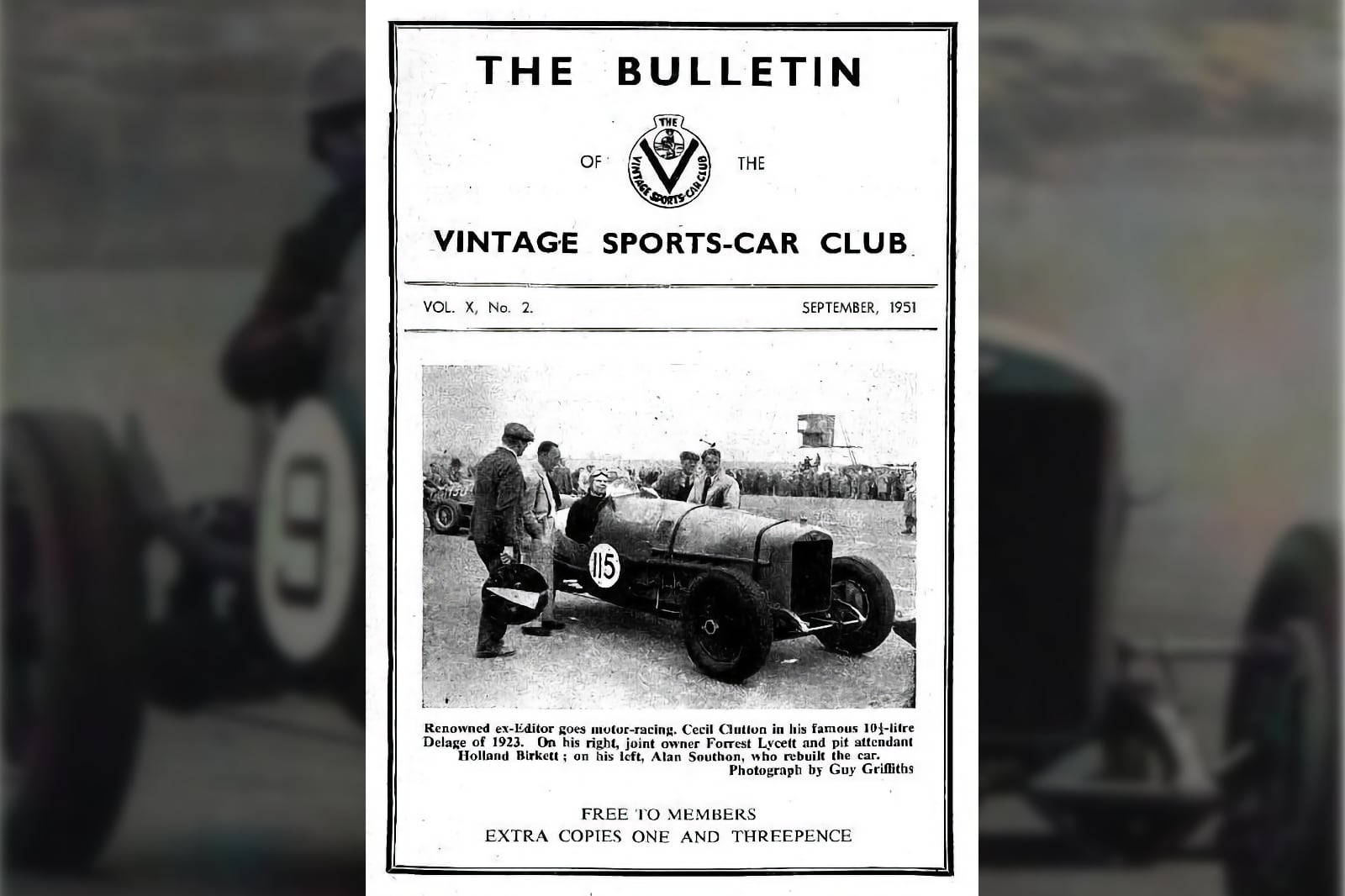

Cecil Clutton on board his 1923, 10 ½ litre, Delage. Image – SJX composite/Bonhams

At the 1936 Annual General Meeting, the debate reached a crisis point. Clutton moved that “vintage” should end on December 31, 1930, while critics argued a fixed date would exterminate the club as eligible cars disintegrated. Clutton argued the opposite. The year 1930 marked a technological watershed, as post-1930 cars featured synchromesh gearboxes, softer suspensions, and mass production. Define the era precisely, he insisted, and you create value. Scarcity becomes a preservation incentive. His motion was adopted with a vote of 23 to 5 in favour.

The decision proved consequential. By establishing clear boundaries, that vintage cars had to have been manufactured between 1919 and 1930, Clutton created a category with permanent meaning, eventually adopted worldwide. His prediction that scarcity would drive preservation rather than extinction proved correct; his relationship with the Itala exemplified his philosophy.

Cecil Clutton and the Delage make the cover of the September 1951 Vintage Sports-Car Club bulletin. Image – SJX composite/VSCC

Editorial influence

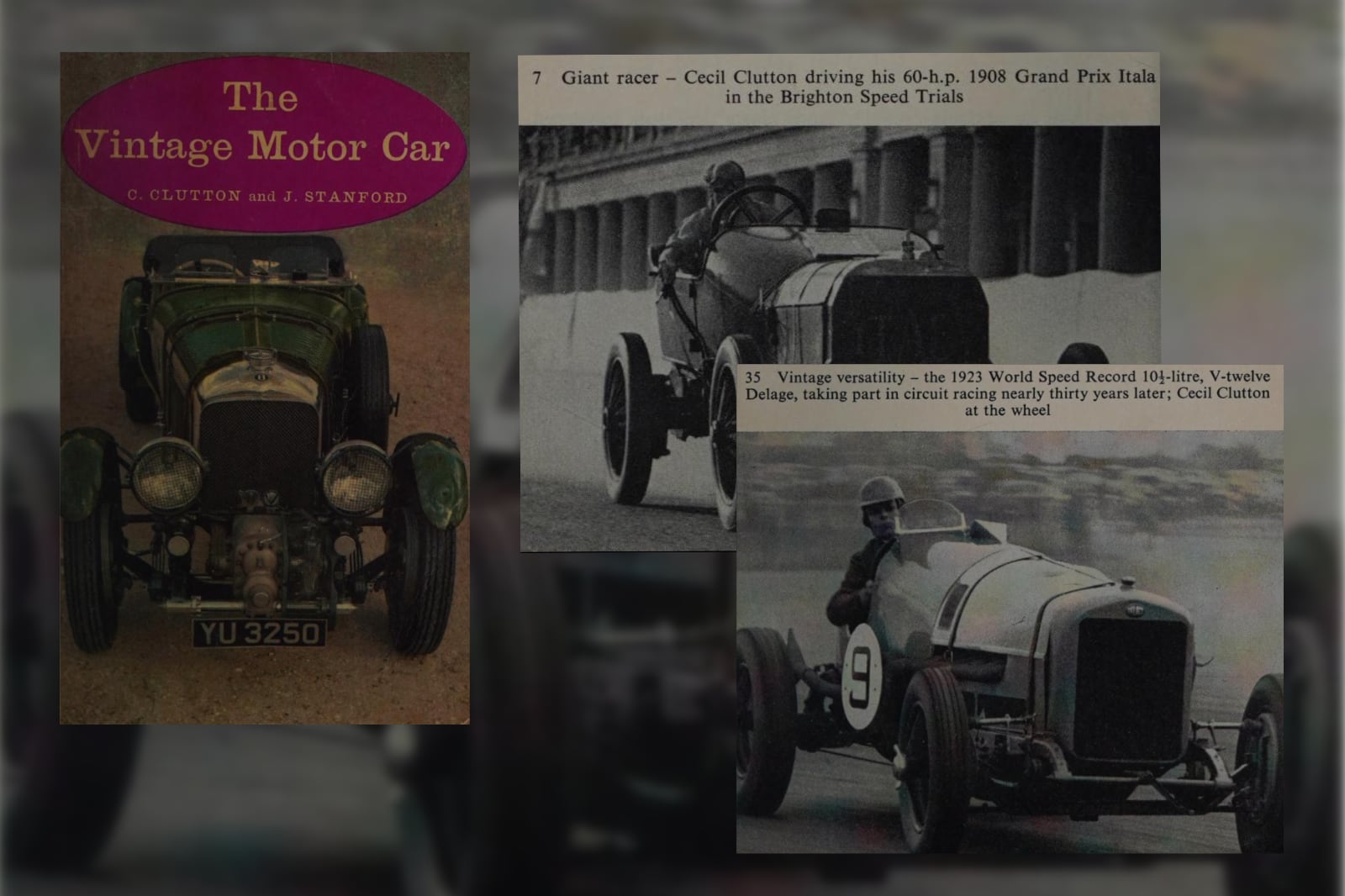

Between 1935 and 1951, Clutton edited the VSCC Bulletin. From 1948 to 1954, he edited Bugantics for the Bugatti Owners Club. His literary output reshaped how Britain understood its automotive heritage. His book The Vintage Motor Car (1954, co-authored with John Stanford) became a foundational text. The Racing Car: Development and Design (1956) provided a technical analysis of the evolution of racing.

His skill as a writer and editor would later have significant implications for the field of horology.

”The Vintage Motor Car” was published in 1961, and included images of Clutton driving the Itala and the Delage. Image – SJX composite/ © Clutton Family.

The Reform Movement

By 1960, when he met George Daniels, Clutton had already established himself as the defining voice in vintage motoring. But his influence extended beyond cars. Clutton’s engagement with pipe organs dated from his school years at Worcester, but his influence on the field emerged forcefully during the 1950s.

By then, he had become a leading voice in the British Organ Reform Movement, bringing to this cause the same combative certainty he’d applied to defining the vintage car era.

The movement sought to overturn the dominance of the Victorian Romantic organ. Clutton argued these organs, which excelled at accompanying Anglican choral services, obscured the polyphonic music of Bach, Buxtehude, and Couperin. The thick tones blurred the counterpoint, and the high wind pressures produced what he considered unnatural pipe speech. The focus on the foundational eight-foot tone at the expense of mixture work left the organs incapable of the clarity and brilliance characteristic of Baroque instruments.

”The British Organ” was published in 1963. Image – SJX composite/ © Clutton Family.

The British Organ (1963), co-authored with Austin Niland, became the manifesto for reform. Clutton advocated for lower wind pressures, allowing pipes to speak with natural bloom. He pushed for vertical tonal structures, building sound upward through the harmonic series (Fundamental, Octave, Twelfth, Fifteenth, Mixture) rather than massing weight at the eight-foot level.

He championed the reintroduction of the Rückpositiv, a division of pipes placed behind the player on the gallery rail, providing immediate, direct sound ideal for contrapuntal clarity. He expressed a preference for tracker action over electro-pneumatic systems, arguing it gave the player better control over phrasing and articulation.

The St. Paul’s Cathedral project in the 1970s gave Clutton the opportunity to implement his ideas at the highest level. Serving as advisor to the surveyor of the fabric, he worked alongside cathedral organist Christopher Dearnley on the rebuilding of Britain’s most prominent organ.

The resulting instrument featured a Dome Chorus, a powerful, mixture-heavy section designed to project sound through the vast, reverberant acoustic. The Royal Trumpets, horizontal reed pipes installed at the West End, provided ceremonial power. The building’s vast volume and substantial reverberation time allowed even aggressive mixing to blend into a coherent ensemble sound. The organ could handle Bach’s fugues with crystalline clarity and still support state occasions.

St. Paul’s Cathedral organ adapted to Cecil Clutton’s specifications. Image – SJX composite/Wikipedia

In the British Organ, Clutton dismissed Victorian achievements as representing a “tonal dead end.” This assessment would later draw criticism from scholars who viewed the judgment as overly harsh, but it galvanised change in a field that had grown complacent.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Clutton was considered part of the “organ mafia”, a small group of influential consultants including Ralph Downes, Peter Hurford, and Dr Francis Jackson. Because Clutton had no commercial ties to organ builders, his advice appeared impartial to church committees. Critics argued he lacked the practical training to fully understand the consequences of his recommendations, sometimes forcing builders to execute designs that were theoretically sound but acoustically harsh in practice.

Yet even critics acknowledged that Clutton’s force of personality had been necessary. He compelled builders to study Continental traditions rather than simply replicating Victorian formulas, forcing the profession to grapple with questions about repertoire, acoustic context, and historical authenticity that it had been avoiding.

The precision period

By the time Clutton met George Daniels in 1960, he had already established himself in horological circles. He was a founding member of the Antiquarian Horological Society established in 1953, and had recently been appointed editor of Antiquarian Horology, a position he would hold from 1960 to 1962. He would later serve as Vice-President of the Society from 1971 until his death and rise to Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers in 1973-1974.

His approach to collecting differed fundamentally from prevailing practice. Before Clutton’s influence, watch collecting focused primarily on decorative arts. Collectors prized enamel cases, jewelled automata, and the ornate verge watches of the 17th and early 18th centuries. These objects offered beauty and craftsmanship, but were somewhat indifferent timekeepers.

Clutton redirected attention toward what he termed the “Precision Period,” roughly 1780 to 1830. Over these decades, English makers like John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw, and Swiss-French masters like Abraham-Louis Breguet, transformed the watch from an aristocratic ornament into a scientific instrument. They developed temperature-compensated balances, isochronous springs, and the detent escapement, which enabled a pocket chronometer to keep time within seconds per week.

”Collector’s Collection”, published in 1974, describing Cecil Clutton’s 33 timepieces. Image – SJX composite/ © Clutton Family.

Technical innovation fascinated Clutton more than decorative artistry; he championed these makers because they solved problems. Each addition to the collection illustrated a specific advance in precision timekeeping. In this respect, Clutton’s mindset can be seen as similar to those of contemporaries like Gerd Ahrens and Seth Atwood.

That said, he preferred what he called a “Rational Collection.” For years, he limited himself to exactly 12 watches. The discipline proved exacting: if he acquired a new watch, an existing piece had to be sold. He couldn’t hoard. He had to curate.

The scope of Clutton’s collection ranged from John Wise (circa 1680, early balance spring) through the refinement of the cylinder escapement by Mudge to Arnold’s pioneering chronometers and Breguet’s perpétuelle self-winding watches, and, eventually, the tourbillon’s appearance in Breguet’s work.

Clutton insisted that each watch was kept in working order so that it could be used as intended. A watch that couldn’t keep time was a corpse; historically interesting but functionally dead. He wore his pieces in rotation, subjecting them to daily life, temperature changes, positional variations, and the occasional shock.

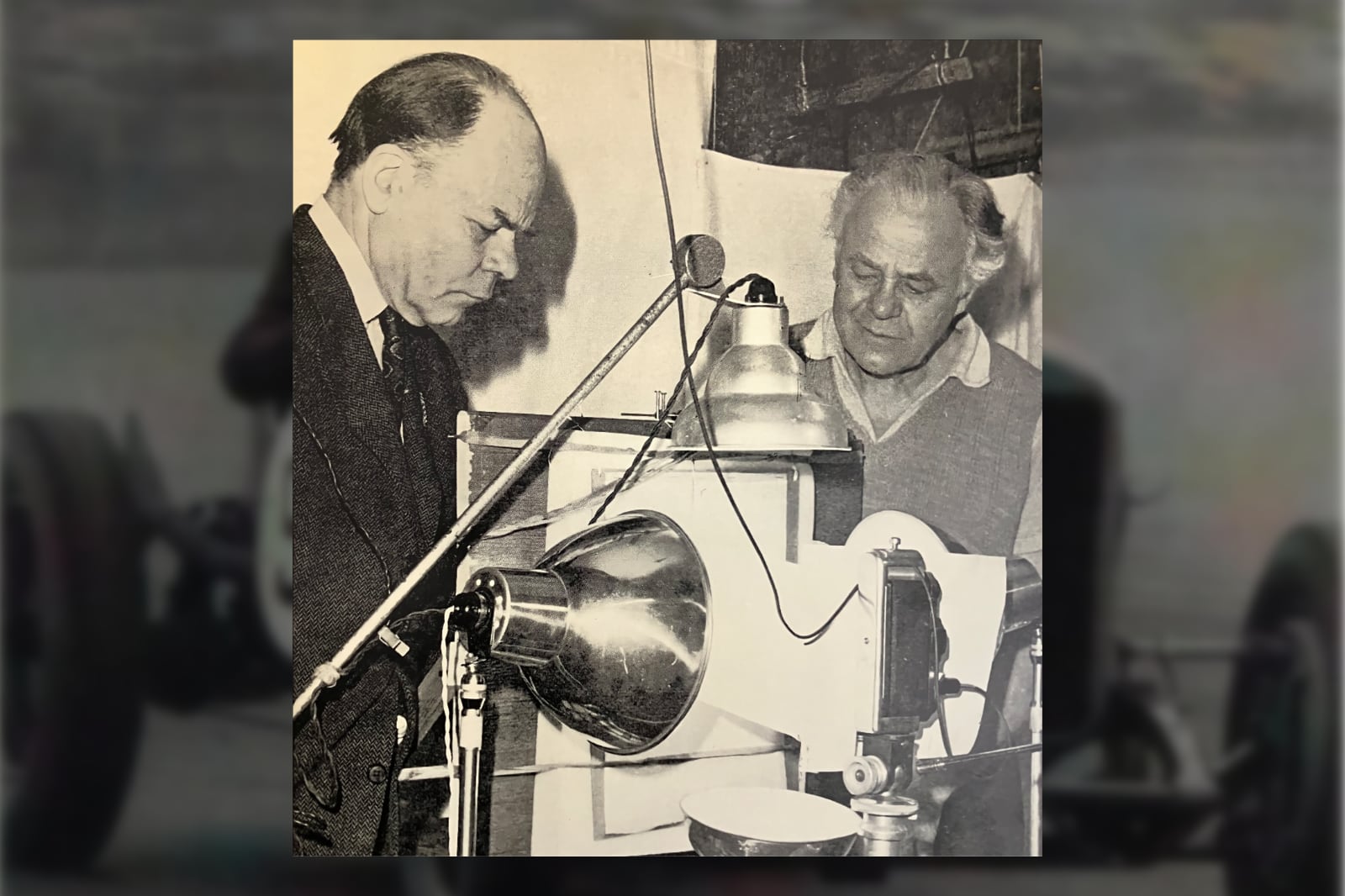

Cecil Clutton (left) and Paterson Fraser’s photography setup designed to eliminate reflections on the glass for the images in Collector’s Collection. Image: SJX composite / © Clutton Family

Preservation through scholarship

Clutton’s passion for preservation extended beyond acquisition. In Collector’s Collection (1974), he detailed forensic investigations into his own pieces. For example, his Thomas Tompion ‘No. 986’ revealed an alteration under examination. The number appeared to read ‘986’, but Clutton discovered that in 1717 a dealer had added a ‘9’ to the original ’86’ after Tompion’s death to make the watch appear newer and more fashionable. The added digit cut through the gold plating, but beneath the dial the unaltered ’86’ remained visible.

Such detective work demonstrated that historical understanding required physical engagement with objects. You couldn’t learn everything from books and photographs. You had to handle the watch, examine it under a magnifying lens, and compare its construction with authenticated examples.

The friendship with Daniels, which began at the 1960 motor race, deepened through regular visits to Blackheath, where Clutton gave Daniels access to his collection. For a self-taught watchmaker, this proved transformative. Daniels could handle Breguet’s work, Arnold’s chronometers, the masterpieces that represented the Precision Period’s apex. He could disassemble these watches, study their construction, and understand the thinking that guided their makers.

The ex-Clutton Breguet No. 15. Image – SJX composite/Breguet

In 1965, Clutton and Daniels published Watches. The book combined Clutton’s historical vision, tracing the evolution from the balance spring’s invention around 1675 to the perfection of the marine chronometer, with Daniels’ technical drawings. For the first time, collectors could examine large-scale photographs of escapements and study the detent’s geometry, the impulse jewel’s relationship to the balance roller, and the locking face that held the train at rest.

The book educated readers to see watches as their makers had seen them: as mechanisms first, and ornaments second. Aesthetic beauty emerged from functional elegance. A well-designed escapement possessed visual grace because its geometry served a purpose. Watches became the standard text for the field, shifting the focus of collecting toward technical appreciation.

The ex-Clutton Arnold & Son No. 21, once owned by Captain Jauncey. Image – SJX composite/Sotheby’s

Daniels’ first client

Shortly after the first edition of Watches was published, Daniels resolved to attempt something unprecedented: build a complete watch entirely by hand. The task required mastering approximately 30 separate trades, including case-making, engine-turning, escapement manufacture, spring formation, jewel setting, filing, and engraving. Since the 19th century, watchmaking had become industrialised, so the idea of a single individual making every part seemed antiquated, if not impossible.

Daniels chose Clutton as his first client. When he announced his intention, Clutton later admitted he felt “deeply flattered and slightly alarmed.” The flattery came from being chosen; his alarm came from wondering whether he could afford such a commission. They settled on a price of £1,900, a substantial sum in 1969 equivalent to about £30,000 today, but far below what such a watch would command if the creation succeeded.

The first Daniels owned by Clutton, completed in 1969. Image – SJX composite/Antiquorum

The project consumed a year. The result featured a pivoted detent escapement within a tourbillon carriage, a technically sophisticated combination. When Daniels delivered the watch in 1969, Clutton examined it thoroughly, then wore it daily in his waistcoat pocket, and showed it to every important horologist he encountered.

The watch proved that a single individual could master all of the trades required to build a complete watch. The achievement represented a philosophical statement about craftsmanship and knowledge: Daniels had demonstrated that comprehensive mastery of an entire craft remained possible in the modern world.

The success led Daniels to begin work on a second commission incorporating an even more ambitious innovation: a new escapement. By the early 1970s, he had developed his Independent Double-Wheel Escapement, a design that improved on A.-L. Breguet’s ill-fated échappement naturel by powering each escape wheel with its own independent gear train.

When Daniels completed the watch in 1976, Clutton was so impressed that he proposed an exchange: he would return his tourbillon watch to Daniels and take delivery of the new double-wheel watch. The exchange completed, Clutton subjected the unique prototype to rigorous testing, wearing it daily during a month-long business trip to Tokyo.

He meticulously recorded the watch’s performance. Upon returning to London, he reported to Daniels that the watch had lost less than one second over the course of 30 days. He would go on to wear the watch for the rest of his life, subjecting it to 15 years of daily use on business trips and to race meetings, keeping methodical records all the while.

These results carried profound implications for an industry facing extinction in the face of quartz technology. Clutton’s Tokyo experiment proved that a properly designed mechanical watch could rival quartz performance in practical use; Daniels later used Clutton’s results when approaching Swiss manufacturers with his innovations.

The bequest

Cecil Clutton collapsed in a London church in February 1991 at age 81. His death came suddenly, a heart attack, presumably, in a building where he had volunteered for decades, attending to organs and performing menial tasks to ensure the fabric remained functional.

The Times published a substantial obituary detailing his wide-ranging professional accomplishments, but struggled to encompass a man who had dominated three distinct fields while maintaining a full-time career in property surveying. Motor Sport magazine published a tribute in its March 1991 issue, calling him “the 100% amateur enthusiast.”

George Daniels wrote a tribute in the Horological Journal for March 1991, describing Clutton’s “mild and amusing eccentricity.” He recounted the cold marble table, the strict limit of six utensils, and his home in Blackheath that had become a salon for mechanical expertise. Daniels emphasised Clutton’s generosity with young enthusiasts, including his willingness to answer “the most immature questions” with “kindly patience.”

The tributes revealed patterns. Multiple writers emphasised that while Clutton was an amateur, pursuing his interests for love rather than profit, he was never amateurish. His books had become standard texts, and his technical knowledge often exceeded that of specialists.

Daniels’ tribute included a melancholy observation, noting that Clutton had devoted decades to his parish church, sweeping the floors, polishing the brass, and maintaining the organs. Yet, years after Clutton’s death, Daniels found nothing to indicate that Clutton had ever existed there. The building stood, the congregation continued, but the man who tended both had vanished.

The second Daniels owned by Clutton, completed in 1976. Image – SJX composite/The British Museum

Fortunately, Clutton’s horological legacy proved more lasting. The original Daniels tourbillon from 1969 would eventually sell at auction for record prices, helping establish the market for independent watchmaking. The 1976 watch, with its groundbreaking independent double-wheel escapement, was donated to the British Museum per Clutton’s bequest, catalogued under inventory number 1991,0406.1. The gift carried specific instructions that the watch should remain in working order, capable of being wound and set. Even in death, Clutton insisted on function.

The rest of Clutton’s “Rational Collection”, assembled over six decades, was dispersed after his death. Each watch had represented a specific advance in precision timekeeping, from the early balance spring through the detent chronometer to the modern revival of independent watchmaking. Several pieces entered institutions and private holdings, where they continue to inform contemporary scholarship.

The structures Clutton built within his three chosen fields continue functioning. The “vintage” classification is a permanent category because he successfully argued for a fixed definition in 1936. Even the Itala itself, later acquired by George Daniels, still races at vintage events. The reformed organs still sound in British cathedrals. The 1976 watch ticks in the British Museum, maintained in working order per his instructions. Sixty years of conviction, embodied in machines that continue their service because their steward refused to let them fall silent.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges James Nye, Chairman of the Antiquarian Horological Society, and David Newman for facilitating access to the Clutton family, who generously gave permission to reproduce images from The Collector’s Collection (1974). Particular thanks to Nigel Clutton for his generosity.

Back to top.