Historical Perspectives: The Rise and Fall of Brazil’s Watch Clubs

Pioneers in making luxury watches accessible.

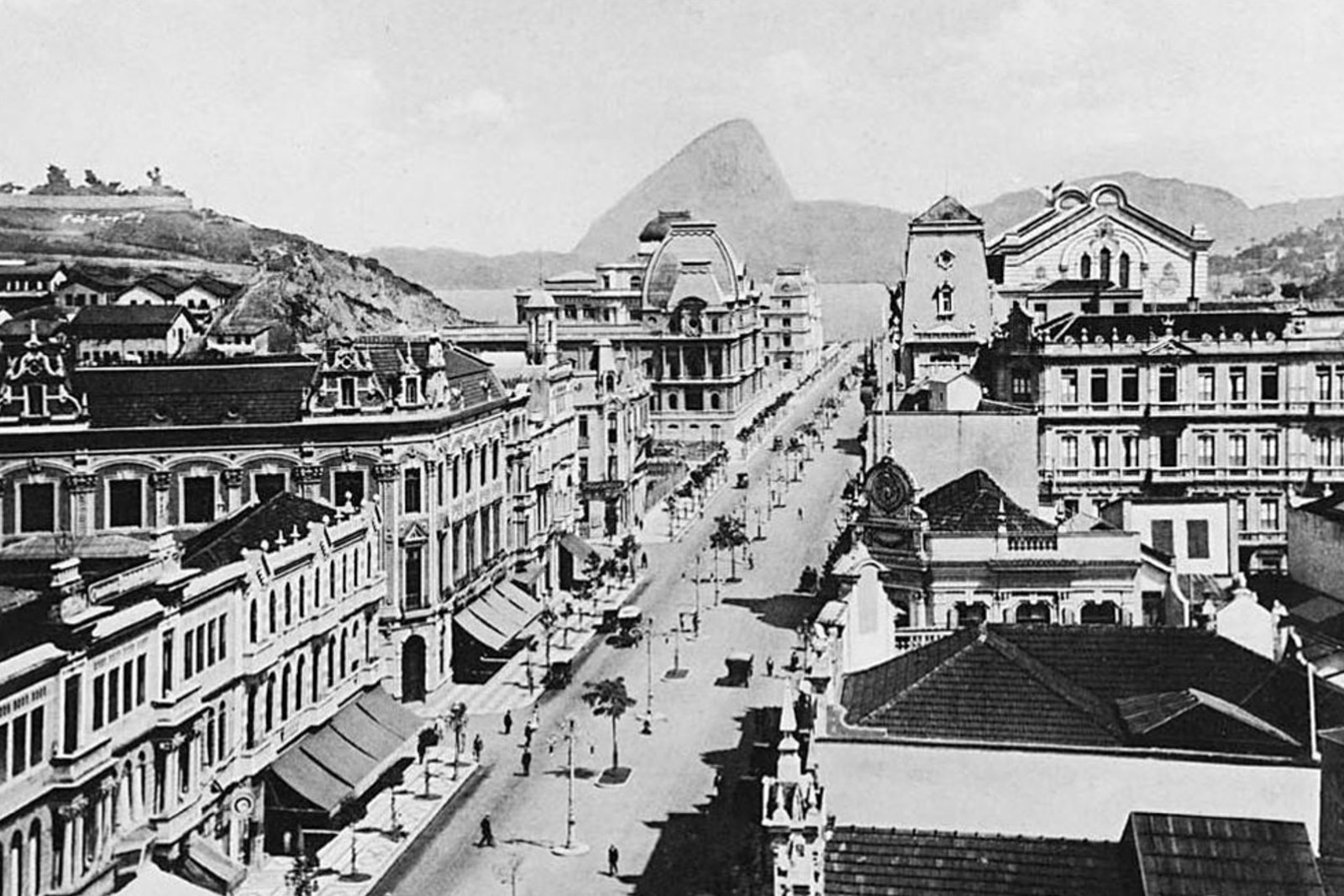

At the dawn of the 20th century, Brazil’s cities were brimming with energy, driven by booming commodity markets. In Rio de Janeiro, trams clattered along bustling streets while conversations about ambition and progress filled the air in crowded cafés. Few aspirations were as compelling for the growing middle class, eager to leave their mark in this modernising world, as owning European luxury goods. And among these, nothing spoke of sophistication and success quite like a fine watch.

For many Brazilians, timepieces from brands like Patek Philippe, A. Lange & Söhne, and Vacheron Constantin were the ultimate symbols of precision and craftsmanship. Yet, their presence was confined to gleaming shop windows along the most prestigious shopping streets, tantalising but out of reach for all but the wealthiest. The dream of owning one of these masterpieces seemed no closer than the distant European watchmaking centres where they were crafted.

But Brazil found a way to close this gap. Here, the concept of watch clubs took shape—an innovative model blending weekly instalments with the thrill of a lottery draw. This system turned the unattainable into something not just possible but accessible. Spearheaded by visionary retailers and embraced by Europe’s finest watchmakers, the clubs reflected Brazil’s unique ability to adapt global trends to its local reality.

Three retailers organised the most iconic watch clubs and positioned themselves at the forefront of this movement: Gondolo & Labouriau with Patek Philippe, whose system set the template others would follow; Frederic Krussmann with A. Lange & Söhne, with its distinctive and generous approach; and Casa Standard with Vacheron Constantin, which spread the phenomenon across the nation. Together, their stories illuminate a singular moment in horological history—when dreams of prestige and precision were, for a time, just a draw away.

(Pictured above: “The Gondolo Watch Gang” captured by Gondolo & Labouriau in 1907. Image – Patek Philippe)

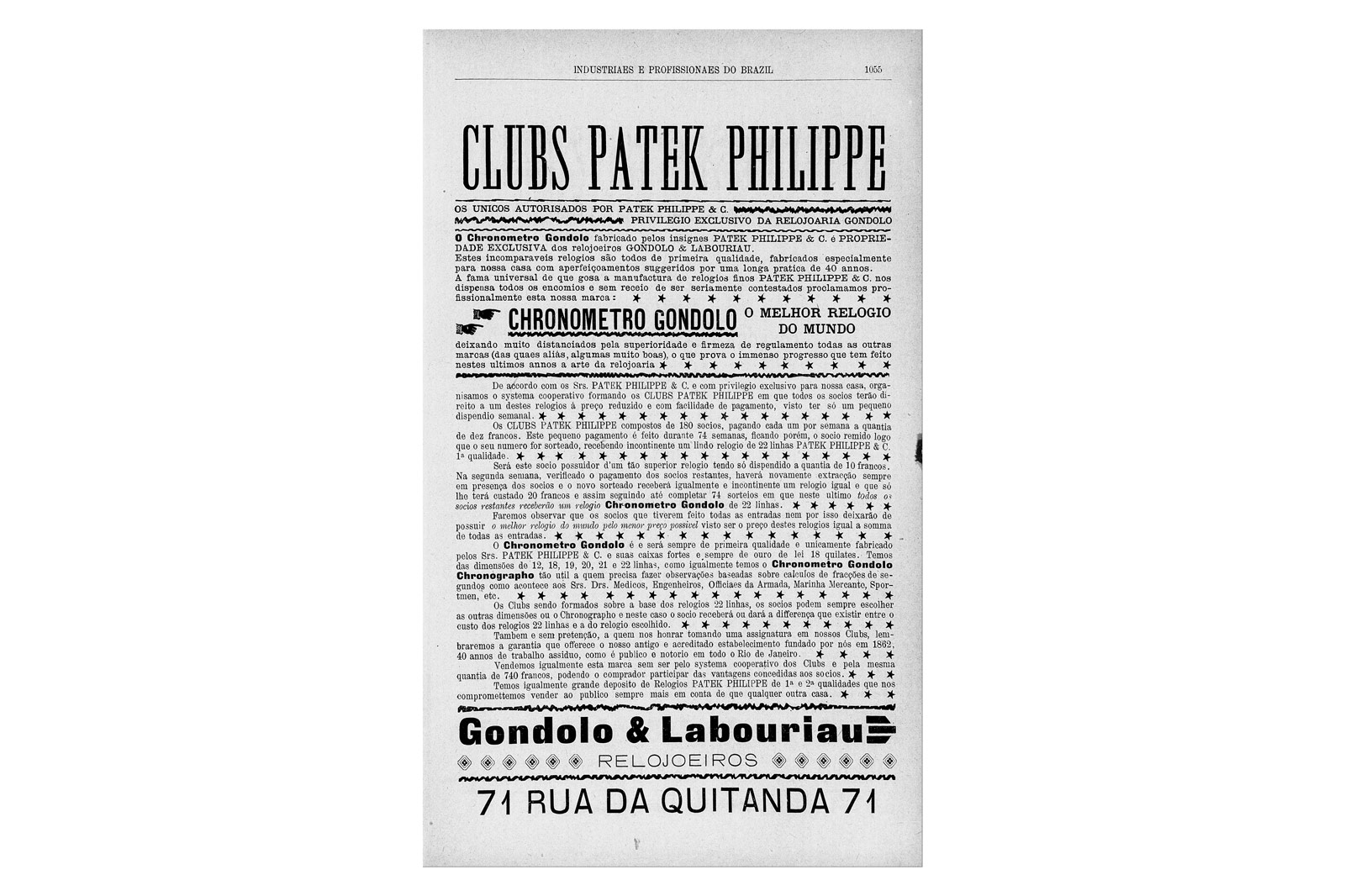

The “Clubs Patek Philippe”: Setting the Foundation

The seeds of Brazil’s watch club phenomenon were planted by Gondolo & Labouriau, an ambitious watch retailer in Rio de Janeiro founded by Carlos Gondolo and Antoine Labouriau.

Established in 1891, the shop quickly became synonymous with exclusivity and refinement, cementing its reputation as the exclusive and official representative of Patek Philippe in Brazil. This groundbreaking partnership redefined luxury for a new audience and proved transformative for the Swiss brand and the Brazilian watch scene.

Patek Philippe Chronometro Gondolo gold cased pocket watch. Image – Christie’s

At the heart of their collaboration was the creation of the Chronometro Gondolo, a timepiece explicitly tailored for the Brazilian market. Patek Philippe crafted this watch to meet the retailer’s specifications, blending durability, precision, and elegance. The Chronometro Gondolo quickly became the symbol of status and achievement for Brazil’s elite, an object as rare and desirable as the lifestyle it represented – in fact, “Patek” became synonymous with “watch”.

In 1901, Gondolo & Labouriau introduced their revolutionary watch clubs, allowing 180 members to pay weekly instalments of 10 francs over 74 weeks. Each week, a draw determined who would receive their Chronometro Gondolo early, with no further payments required. By the end of the cycle, every participant would own a coveted gold-cased, 22-ligne Patek Philippe pocket watch.

The first draw, held on December 10, 1901, named Luiz Maria Monteiro of Rua da Luz the inaugural winner. His success was celebrated widely, inspiring curiosity and enthusiasm for this new path to luxury. Weekly gatherings at Gondolo & Labouriau’s shop on Rua da Quitanda were lively affairs, filled with speculation and excitement. The advertisement for the clubs captured their appeal succinctly:

“The Patek Philippe Clubs are composed of 180 members, each paying a weekly instalment of ten francs. This modest payment is made over 74 weeks, and the member whose number is drawn each week immediately receives a beautiful 22-ligne Patek Philippe & Co. watch of the finest quality. If their number is drawn before all instalments are paid, they are exempt from future payments.”

Ad run in 1902 in the Brazilian Almanak Laemmert. Image – Almanack Laemmert

By 1908, the clubs had expanded beyond Rio de Janeiro, with branches in São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and other states. Gondolo & Labouriau’s system didn’t just make Patek Philippe watches accessible—it transformed them into cultural icons deeply embedded in Brazilian society.

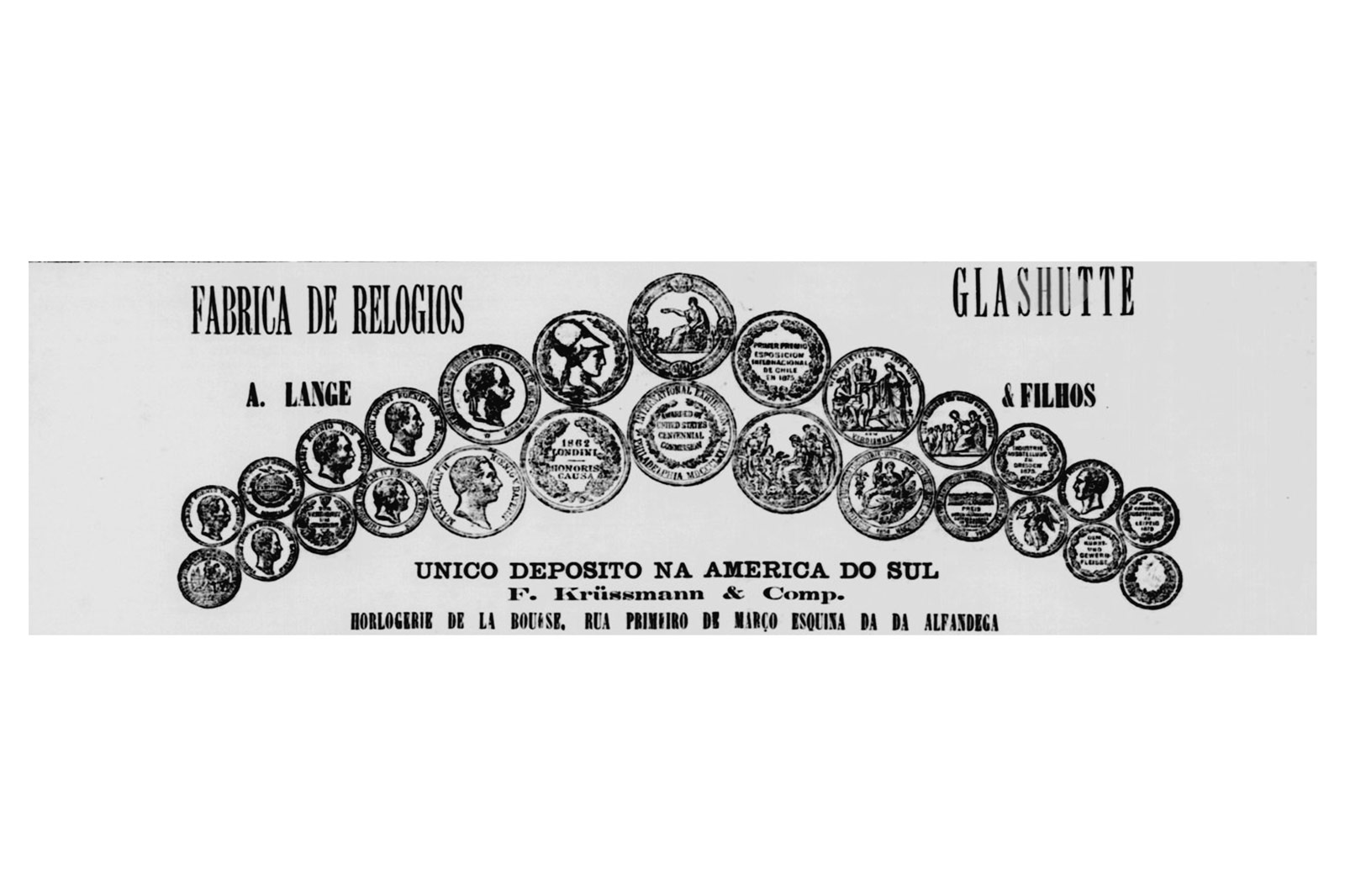

Following the remarkable success of Gondolo & Labouriau’s Patek Philippe Clubs, Frederic Krussmann introduced a new chapter in Brazil’s horological history with the A. Lange & Söhne clubs. Here, innovation took on a uniquely generous form.

Frederic Krussmann´s Lange & Söhne Clubs: Generosity and Innovation

In 1905, inspired by Patek Philippe’s success, Frederic Krussmann launched the Lange & Söhne Clubs. A seasoned watchmaker and the exclusive representative of A. Lange & Söhne in Brazil since 1881, Krussmann was already renowned for his expertise and dedication to quality. By introducing the Lange Clubs, he expanded access to luxury and elevated the club model with unique features.

Lange & Sohne made for Frederic Krussmann. Image – Dr. Crott Auktionen

The A. Lange & Söhne Clubs mirrored the structure of the Gondolo & Labouriau Clubs: 170 members paid weekly instalments of 10 francs over 70 weeks. Every Saturday, participants gathered at Krussmann’s shop at their address of Rua do Ouvidor or waited remotely for the results through a network of representatives to witness the eagerly anticipated draw. The lucky winner’s dream of owning a Lange pocket watch was fulfilled early, requiring no further payments.

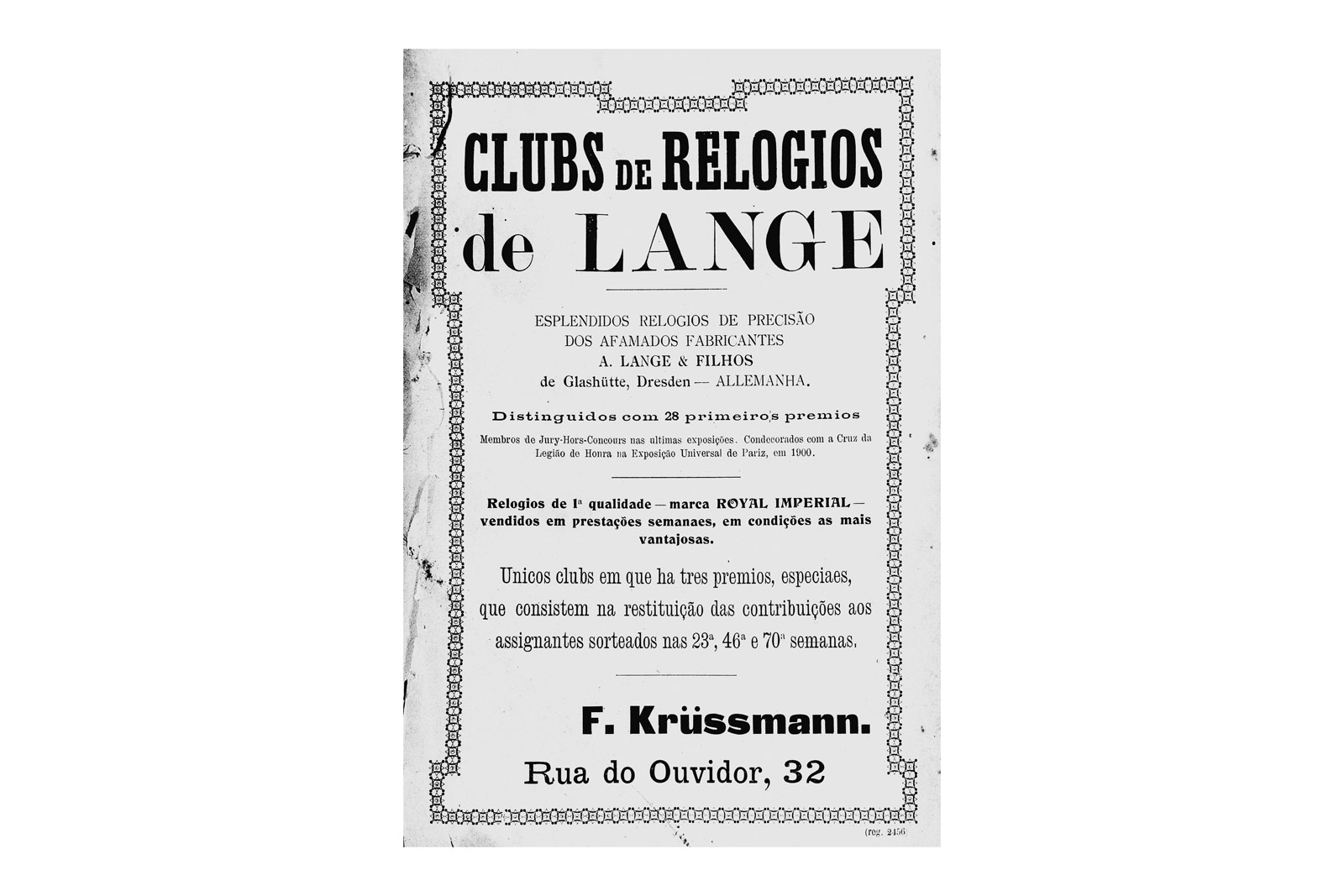

Ad published in december in Jornal do Commercio of Rio de Janeiro. Image – Jornal do Commercio

The first draw, held on January 17, 1905, saw Antonio Joaquim Ferreira, who lived at Rua 1º de Março in Rio de Janeiro, take home the first Lange pocket watch, marking the beginning of a tradition that would endure for years to come.

The Lange Clubs distinguished themselves through their special milestone draws. Winners of the 23rd, 46th, and very last 70th draw received their watches and had all their past instalments refunded—a unique feature that heightened the anticipation of these weeks. A 1907 advertisement described the process:

“Every week, a draw will be held with the presence of the participants, granting a High-Precision Watch to the members whose numbers are drawn in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and following weeks. On the 23rd, 46th, and 70th draws, winners receive a full refund of all instalments paid.”

Ad published in 1905 in the Almanak Laemmert Administrativo, Mercantil e Industrial of Rio de Janeiro. Image – Almanak Laemmert

Lange timepieces were prized for their elegance and resilience in Brazil’s challenging tropical climate. Krussmann’s guarantee of a five-year warranty underscored his confidence in their quality. Combined with the excitement of the clubs, these features cemented Lange & Söhne as a symbol of both precision and achievement in Brazil.

By 1907, the success of these watch clubs had captured the attention of retailers across Brazil. Building on the excitement sparked by the Lange Clubs, Casa Standard, under Arthur Campos’s leadership, elevated the watch club model to an unprecedented national phenomenon with its Vacheron Constantin Clubs.

The Casa Standard Vacheron Constantin Clubs: A National Phenomenon

Building on the excitement and innovation of the Lange Clubs, the concept quickly gained traction among other retailers. By 1907, Casa Standard, under Arthur Campos’s leadership, embraced this model by introducing the Vacheron Constantin Clubs, expanding the phenomenon to unprecedented heights.

Vacheron Constantin Chronométre Royal. Image – Christie’s

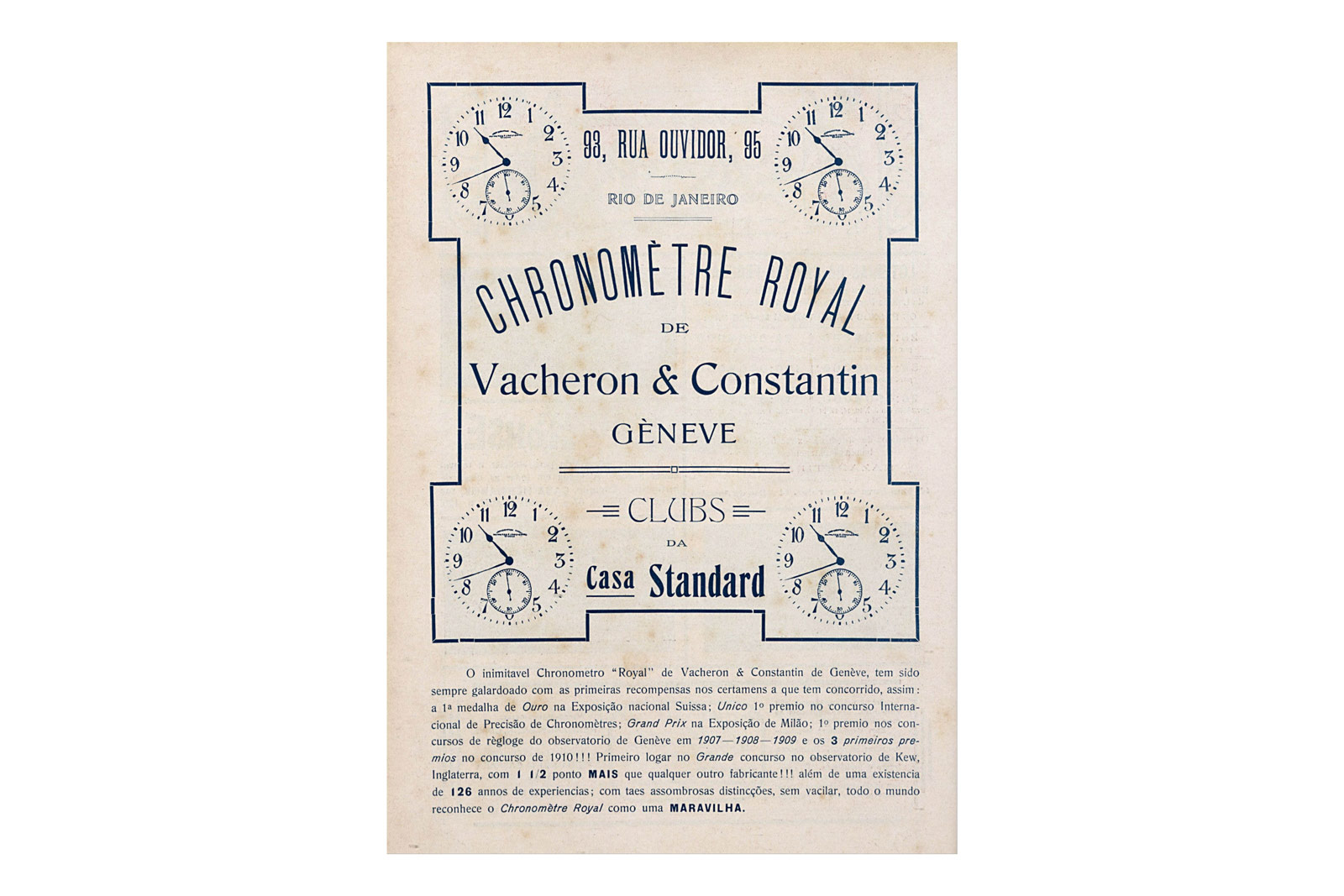

Focused on the prestigious Chronomètre Royal, these clubs offered a new level of accessibility to one of the world’s most respected watchmakers. Casa Standard blended exclusivity with scale and elevated the watch club model to a nationwide phenomenon.

Casa Standard didn’t limit itself to watches. It applied the same club system to other luxury and practical goods, including German Ritter pianos, American Fox typewriters, and other high-value items. Ritter pianos involved 150 weekly draws, while Fox typewriters were part of an 85-week system.

The first draw of the Vacheron Constantin Chronomètre Royal Club, held on October 6, 1907, saw Dr. Eurico de Lemos of Rua da Carioca in Rio de Janeiro become the inaugural winner, sparking excitement and setting the tone for the club’s future success. These clubs operated with well-defined rules, offering transparency and excitement for participants:

“The Standard Clubs offer Vacheron Constantin’ Chronomètre Royal’ watches through a system of weekly draws. Each club consists of 180 members, each paying a weekly instalment of 10 francs. Every Saturday at 2 p.m., one lucky winner is drawn to receive their watch early and is exempt from further payments. By the end of 70 weeks, every member will have received their watch.”

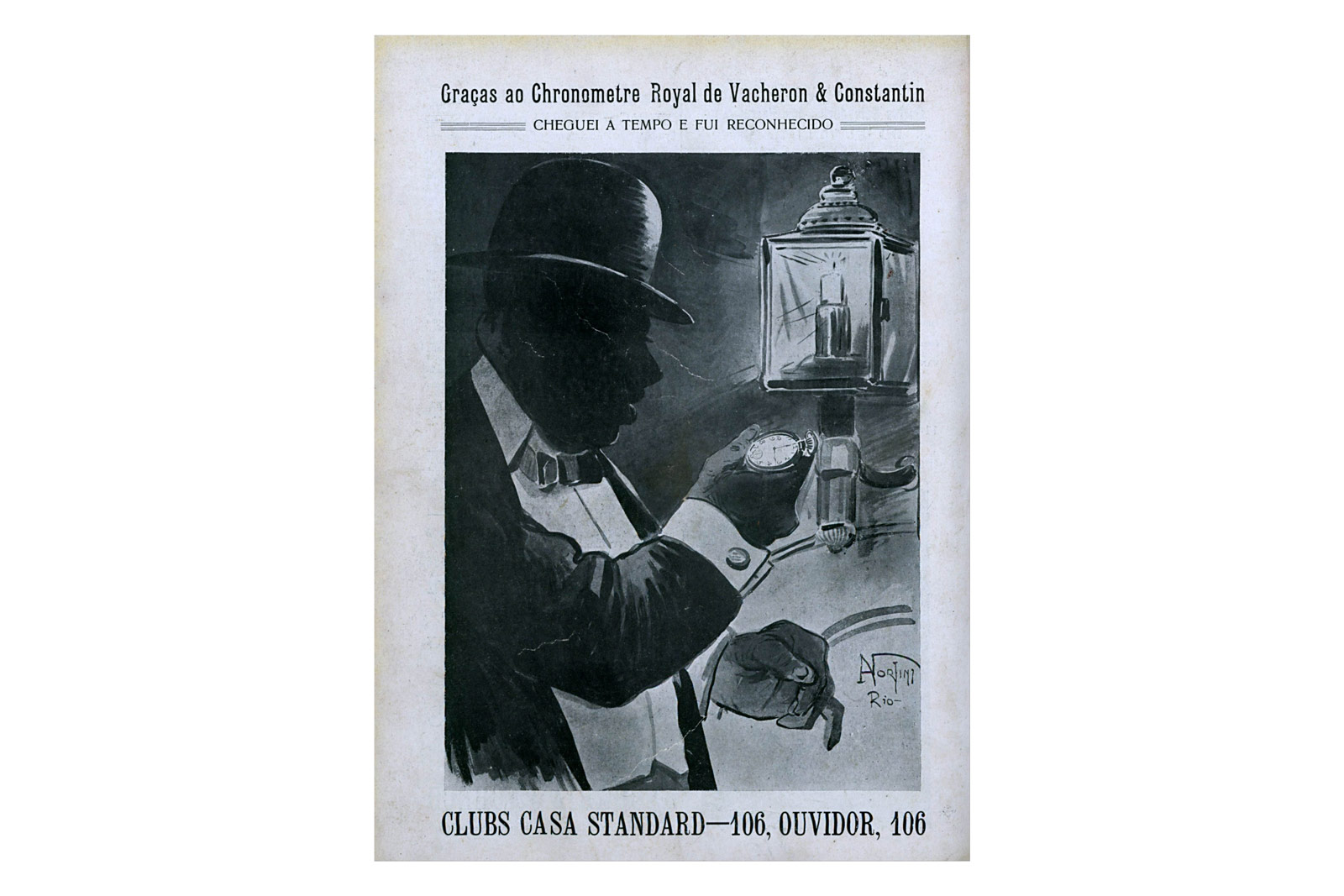

Ad published in March 1911 in the magazine “A Careta”. Image – A Careta

Casa Standard’s extensive nationwide network of representatives allowed the clubs to operate simultaneously in multiple states, extending the reach of the watch clubs far beyond Rio’s vibrant urban centre. It connected participants from diverse regions across Brazil vast regions.

By 1909, 16 clubs were simultaneously active, with accumulated membership exceeding 6,800 throughout the year. The Chronomètre Royal became a status symbol for Brazil’s middle class, combining precision with prestige. The success of the clubs and the detailed structure of the draws ensured the Chronomètre Royal was not only a luxury item but also a shared aspiration for a growing middle class.

A Legacy of Dreams and Precision

The story of Brazil’s watch clubs is more than just a tale of luxury; it reflects a country’s creativity and determination to make the extraordinary accessible. These clubs transformed purchasing a fine timepiece into something far more significant—a shared journey filled with anticipation, celebration, and community.

At a time when such timepieces were prohibitively expensive, these clubs offered a revolutionary alternative: a way to acquire luxury not through wealth alone but through commitment, community, and a touch of luck. They allowed brands like Patek Philippe, A. Lange & Söhne, and Vacheron Constantin to transcend their European origins, embedding themselves deeply into Brazil’s cultural and social landscape.

Rio de Janeiro in 1905. Image – Instituto Moreira Sales

For a brief but golden period, the watch clubs made the unattainable attainable, opening the doors for thousands to own a horological masterpiece. The weekly draws were as much about camaraderie as they were about watches, creating a sense of connection in a rapidly changing world. The winners’ names, called out with fanfare and etched into history, symbolised more than personal success—they embodied the power of aspiration and collective ambition.

Yet, as the 1930s approached, the economic and social currents that had enabled these clubs began to shift. Stricter government regulations and changing financial systems stripped some of the excitement from the process, while the global economic downturn forced many to prioritise necessity over luxury. By the time the last clubs closed their doors, the phenomenon had become a cherished memory of a bygone era.

While the world of horology has evolved, echoes of those early clubs resonate in how collectors and enthusiasts engage with watches today. Global auctions, exclusive events, and limited-edition releases mirror the thrill and anticipation of the weekly club draws, reminding us of the joy of turning aspirations into reality.

Timepieces such as the Chronometro Gondolo and Chronomètre Royal, first introduced to the public through the watch clubs, are underappreciated treasures in the vintage watch market. Their craftsmanship, rarity, and stories make them indispensable to any serious horological collection. They embody the spirit of a time when innovation brought luxury within reach.

Casa Standard Vacheron Constantin Chronométre Royal ad from May 1909. Image – A Careta

Perhaps the watch clubs’ most significant legacy lies in their democratisation of luxury. They demonstrated that fine watchmaking could transcend class and geography, opening the door to an entirely new audience. While today’s high-end watches often seem reserved for an elite few, the spirit of accessibility endures in the passion of collectors who seek not just objects of precision but symbols of shared culture and history.

As we reflect on the rise and fall of Brazil’s watch clubs, we find more than a historical curiosity. We see an enduring spirit that reminds us of how dreams can unite people, no matter the era. For a moment, the world paused, and a dream of precision, craftsmanship, and status came to life—not just for an individual but for an entire community. In those fleeting moments, aspiration transcended circumstance, a spirit that continues to inspire to this day.

Back to top.