Gunsmith Dewey Vicknair Returns with Second Handmade Watch

A regulator-style display.

A year ago, we covered a self-taught watchmaker who built his first piece by watch, Dewey Vicknair. Now the American gunsmith has completed his second watch, a regulator with a jump hour function that’s once again hand-made. He published a comprehensive photo essay detailing the steps in manufacturing the watch, which is a worthwhile read for anyone interested in a contemporary, yet fully manual watchmaking process.

Initial thoughts

The story of Mr. Vicknair is unlike most independent watchmakers. Now in his mid-fifties, he long ago built his reputation as a maker and restorer of firearms before turning to watchmaking. Self-taught, Mr. Vicknair is definitely a quick study; he adapted his metal-working skills to horology and produced his first watch swiftly.

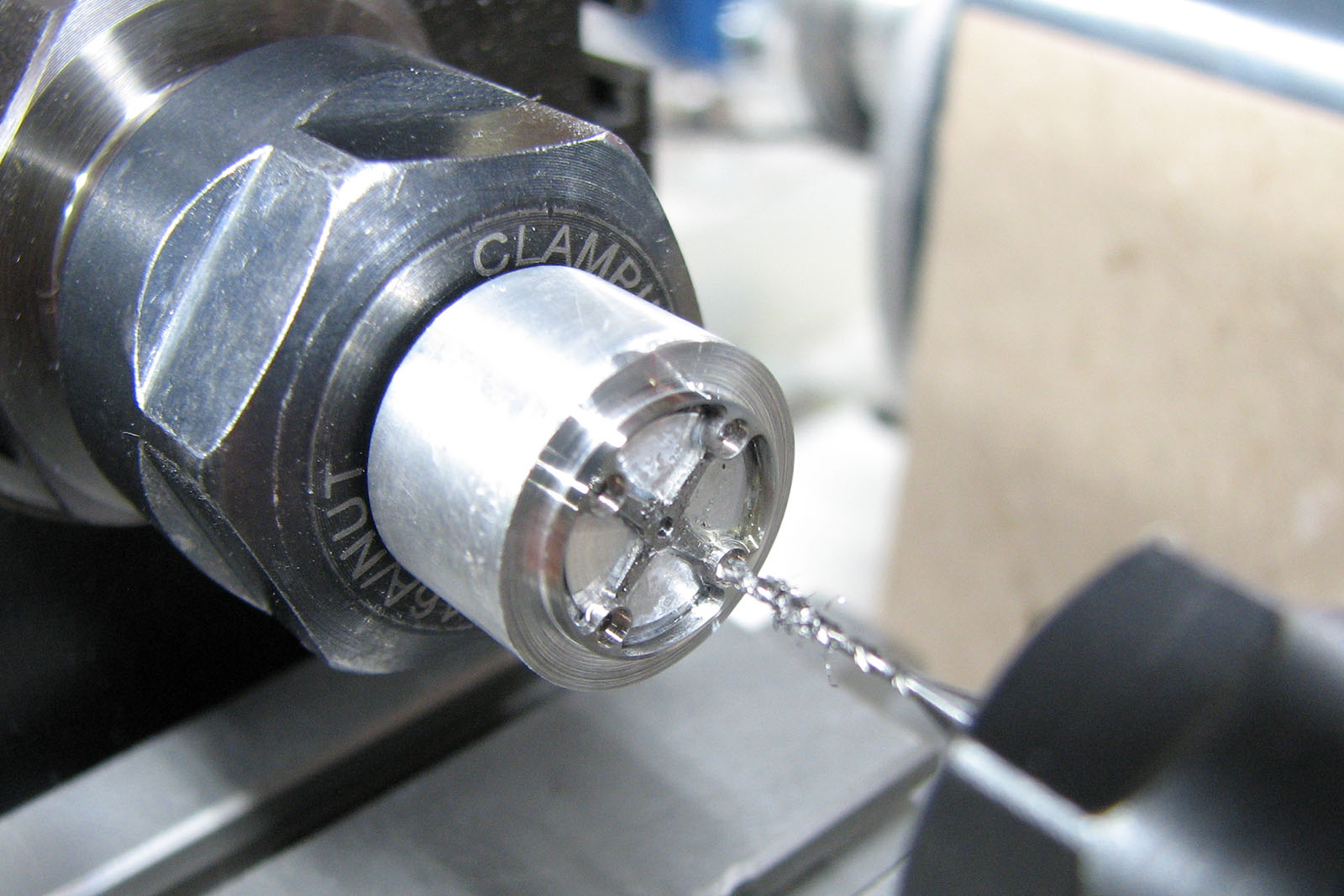

Even more interesting, perhaps, is the way he creates his own tooling. From a vertical drill press to various cutters and even custom tweezers for bending the hairspring overcoil, Mr. Vicknair seems able to build any tool to cater to his requirements.

Artisanal watchmakers usually use restored vintage machines when making watches, but it is very rare that they develop the tools themselves. Mr. Vicknair’s extensive experience as a gunsmith gives him an excellent understanding of machinery that cannot simply be taught in watchmaking schools. His work is clearly that of a very talented mechanical craftsman who just happens to have mastered watchmaking – after having mastered gunsmithing.

The watch itself is presented in a 39 mm steel case – made by Mr. Vicknair himself naturally – and marries classical aesthetics with a gunsmith’s personal touch. There is an open-worked regulator dial, which leaves the jump hour works fully visible.

The design language is not fully cohesive, particularly in terms of the dial, which feels raw, especially with the bright white numerals, but the quality of make is clear. This is especially impressive given that the watch is largely made by hand, with practically every step documented in photos.

Distant Omega roots

As with his first creation, Mr. Vicknair’s latest movement has roots that can be traced back to an Omega cal. 266, “but there is little left of it,” as the watchmaker himself puts it.

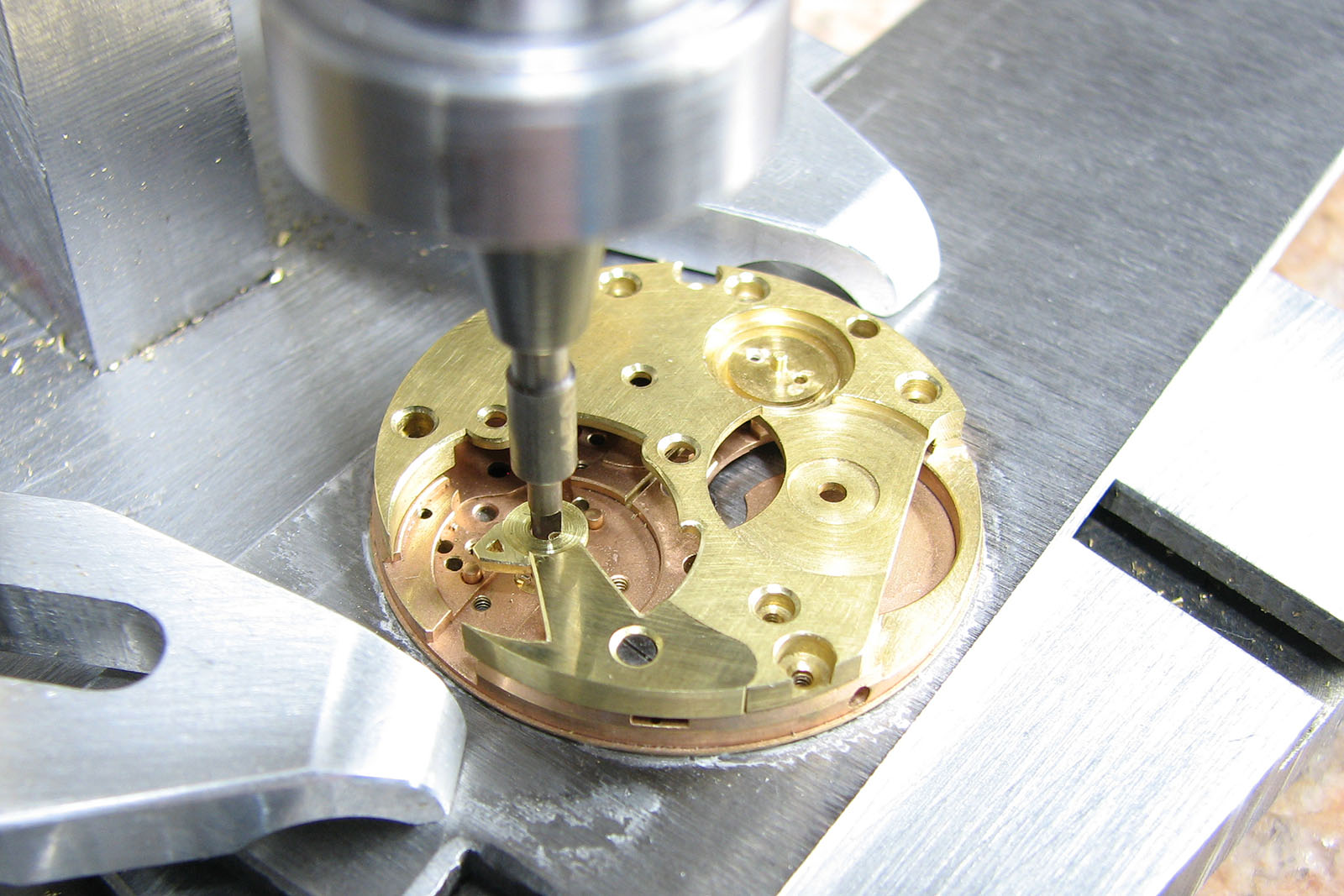

The base plate of the vintage caliber was used, along with the going train and escapement. The baseplate, however, went through extensive tweaks in order to accommodate the jump hour and regulator display conversion.

Milling of the three-quarter plate; the original Omega base plate is used to ensure the correct positioning of jewel holes.

The balance cock was built in a similar manner, starting from a raw piece of brass that was cut and shaved down to the right dimensions. This is a notable achievement as making a balance cock is especially difficult, since the watchmaker needs to take into consideration proper endshake adjustment and tolerances.

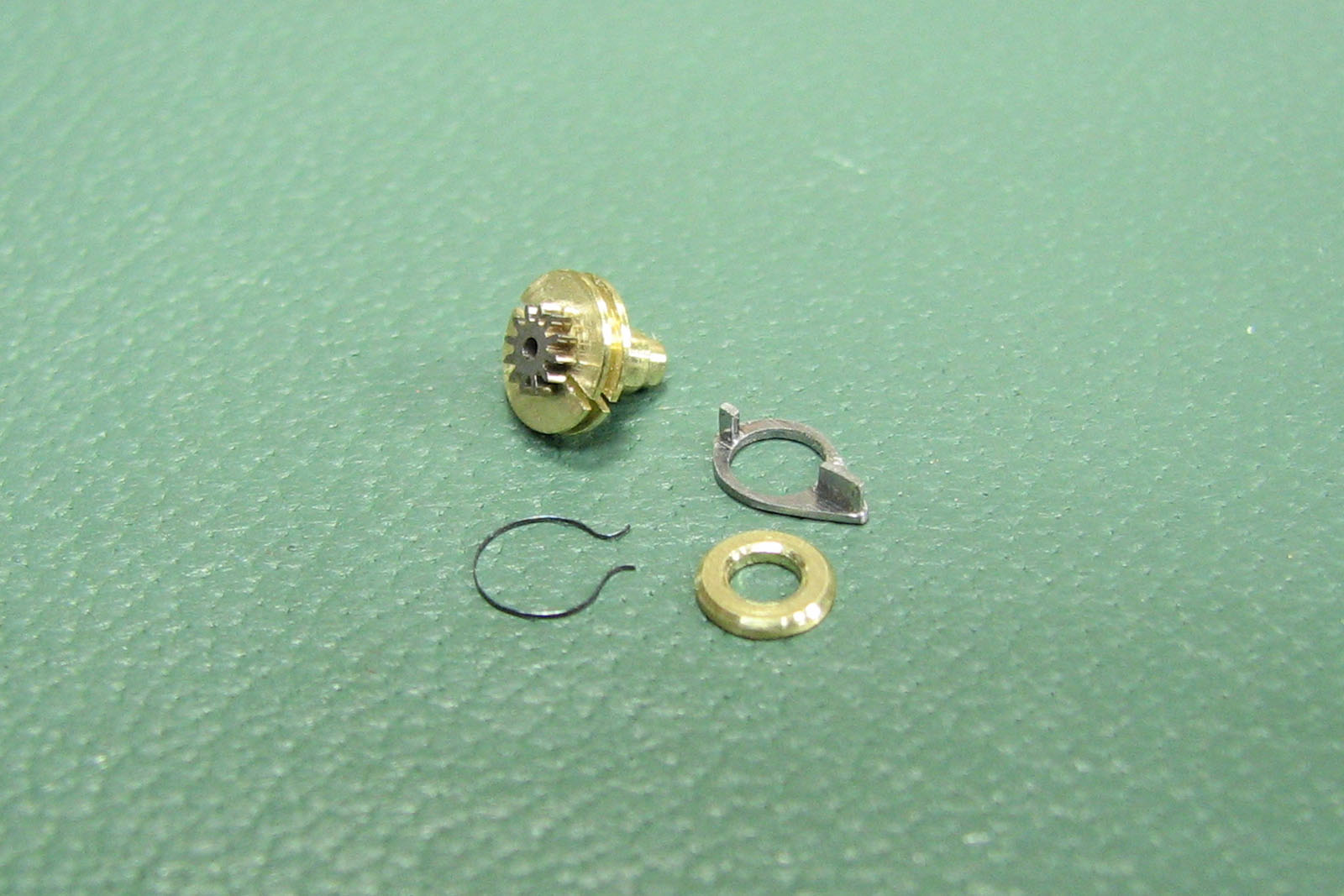

Here is the almost raw brass piece that will eventually turn into the balance cock.

The fully shaped balance cock; the picture shows the milling of the jewel and shock absorber hole.

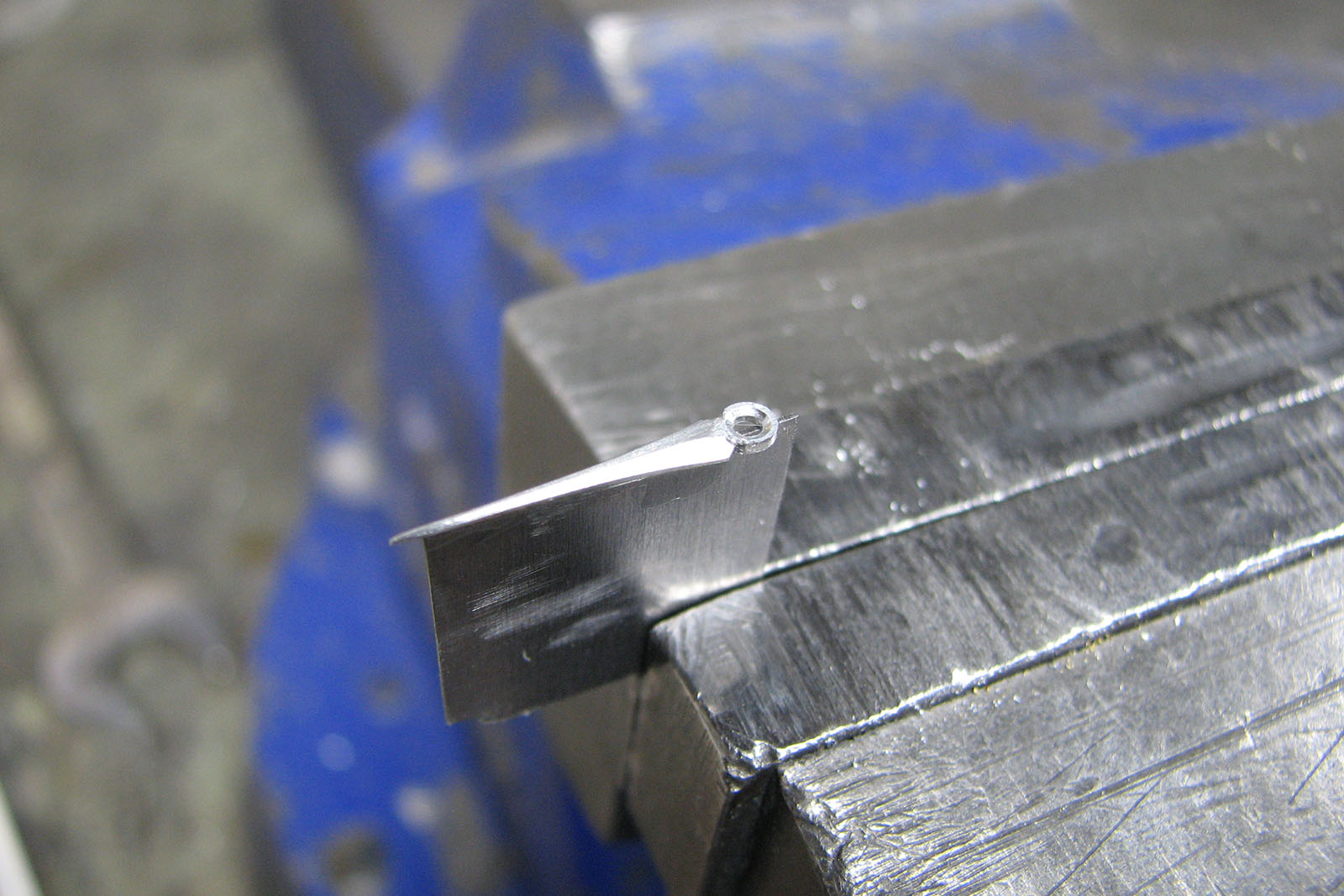

Crafting the blade click spring.

Fine finishing

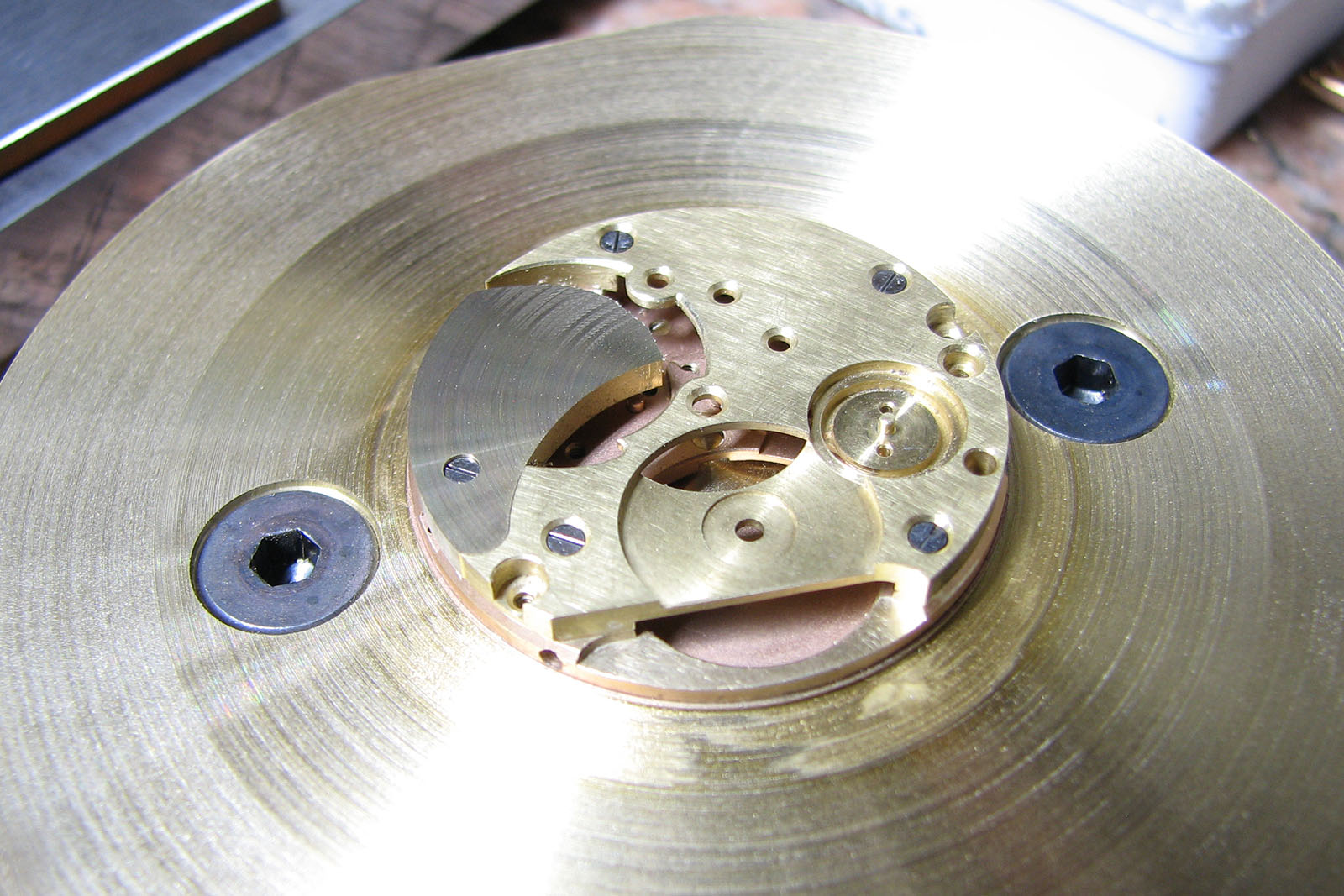

The components are secured by a three-quarter bridge that was hand-made by Mr. Vicknair from a raw brass disk. Compared to his first watch, the second model is decorated in a more classical fashion, with perlage and wide Geneva striping. The components are also gold-plated by the watchmaker at his bench.

Classic finishing with traditional tools.

Almost completed movement, components plated by Mr. Vicknair.

The jewel holes are countersunk and all the edges rounded. The small bridge securing the escapement lever is also adorned with Geneva stripes, as is the spring for the keyless works.

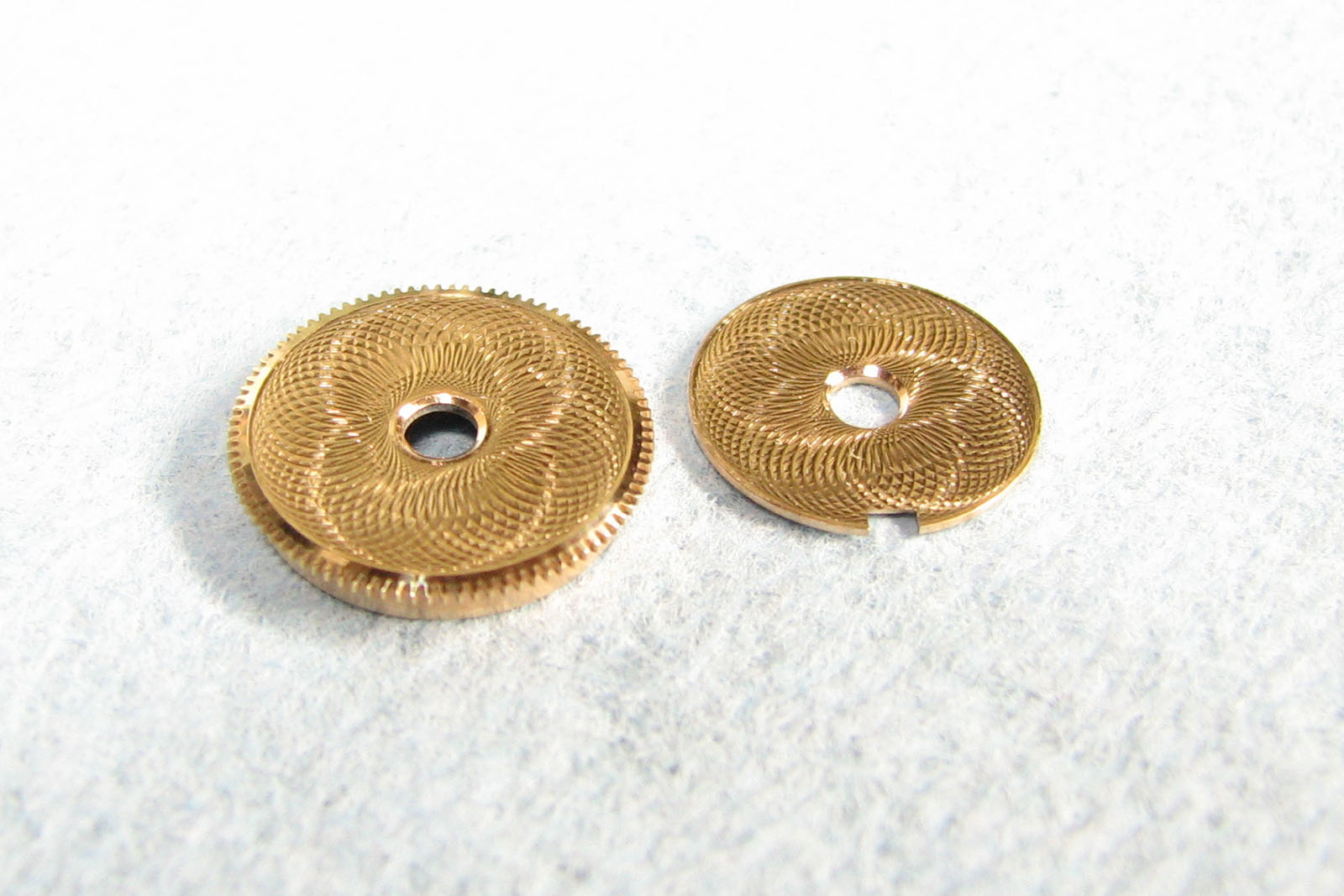

Another interesting choice of finishing is the rich engine-turning on the barrel cover and underside. It is a shame that the wearer can only catch a glimpse of the guilloche surface through narrow cut-outs in the base plate and bridge.

Undoubtedly one of the best finished barrels to be put in a watch.

The pantograph

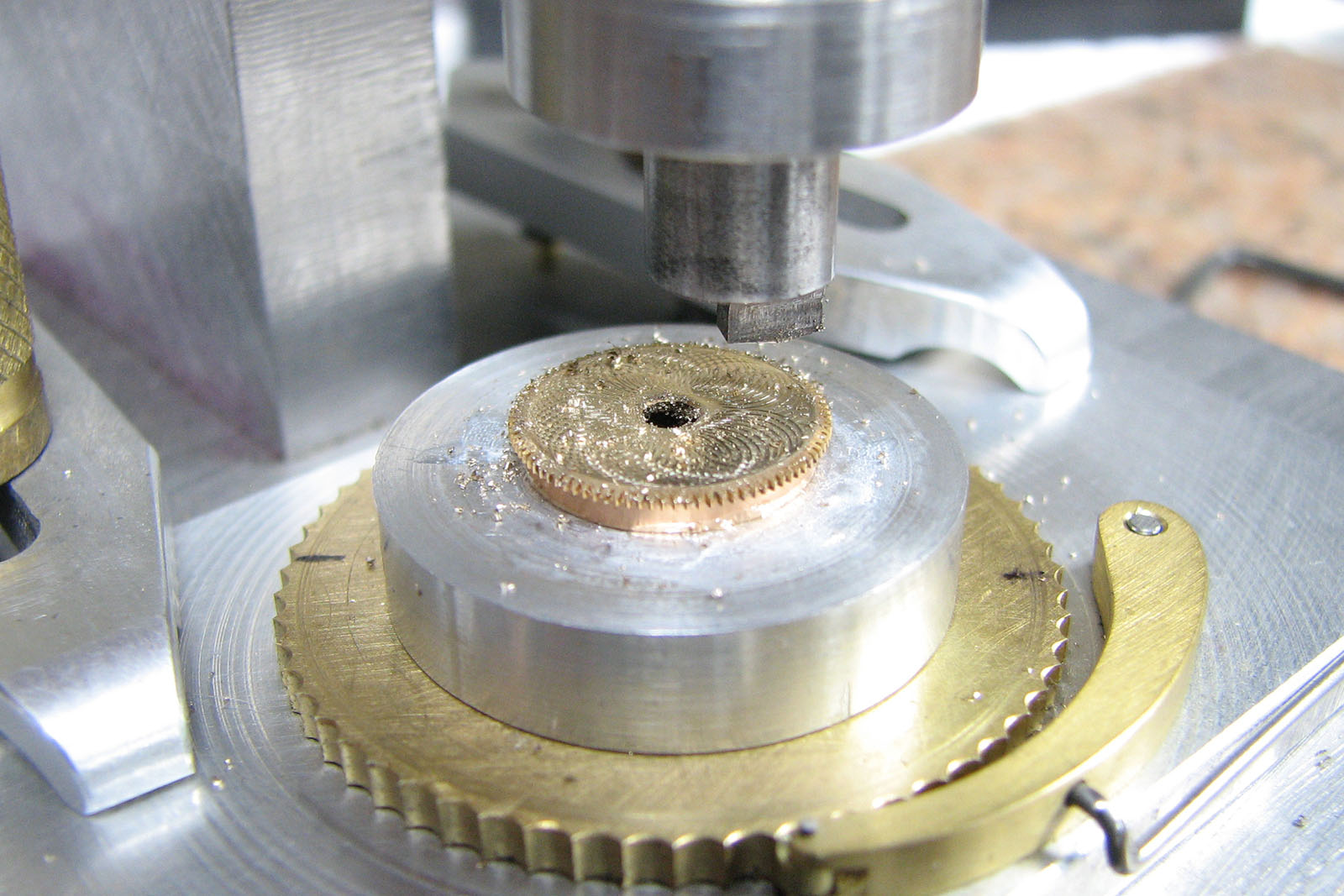

Mr. Vicknair consistently used a pantograph throughout his build. He used the pantograph for skeletonising the barrel click wheel, cutting the balance wheel, and signing the case back.

A pantograph is a mechanical device that allows an exact, two-dimensional trace to be reproduced with precision on a much smaller scale. The technique was famously used by A.-L. Breguet for his “secret signature” on watch dials (and which the brand recently revived for its 250th anniversary Souscription).

Boring holes for the timing weights on the balance that has been previously cut with a pantograph.

The technique relies on first making large-scale mock-ups of the desired patterns, then manually tracing their contours with the pantograph’s stylus. The other end of the pantograph reliably engraves the patterns in metal, at a much smaller scale.

With a pantograph, Mr. Vicknair actually crafted two balance wheels, with the first looking like the typical Gyromax-style balance employed across the higher-end watchmaking. But he ended up scrapping that one, feeling it felt out of place with the classic styling of the rest of the movement. The final balance wheel is a free-sprung version paired with an overcoil hairspring.

Bending the overcoil with the help of customised tweezers.

Dial side

The dial is heavily open-worked and made of several pieces. The dotted and frosted circular tracks bring to mind classic designs from Breguet and George Daniels. While it is certain that the base plate and under-dial works are meant to be the main attraction of the front, the dial feels lacking; the pairing of plain white hour marks with silvery hands is not the most appealing.

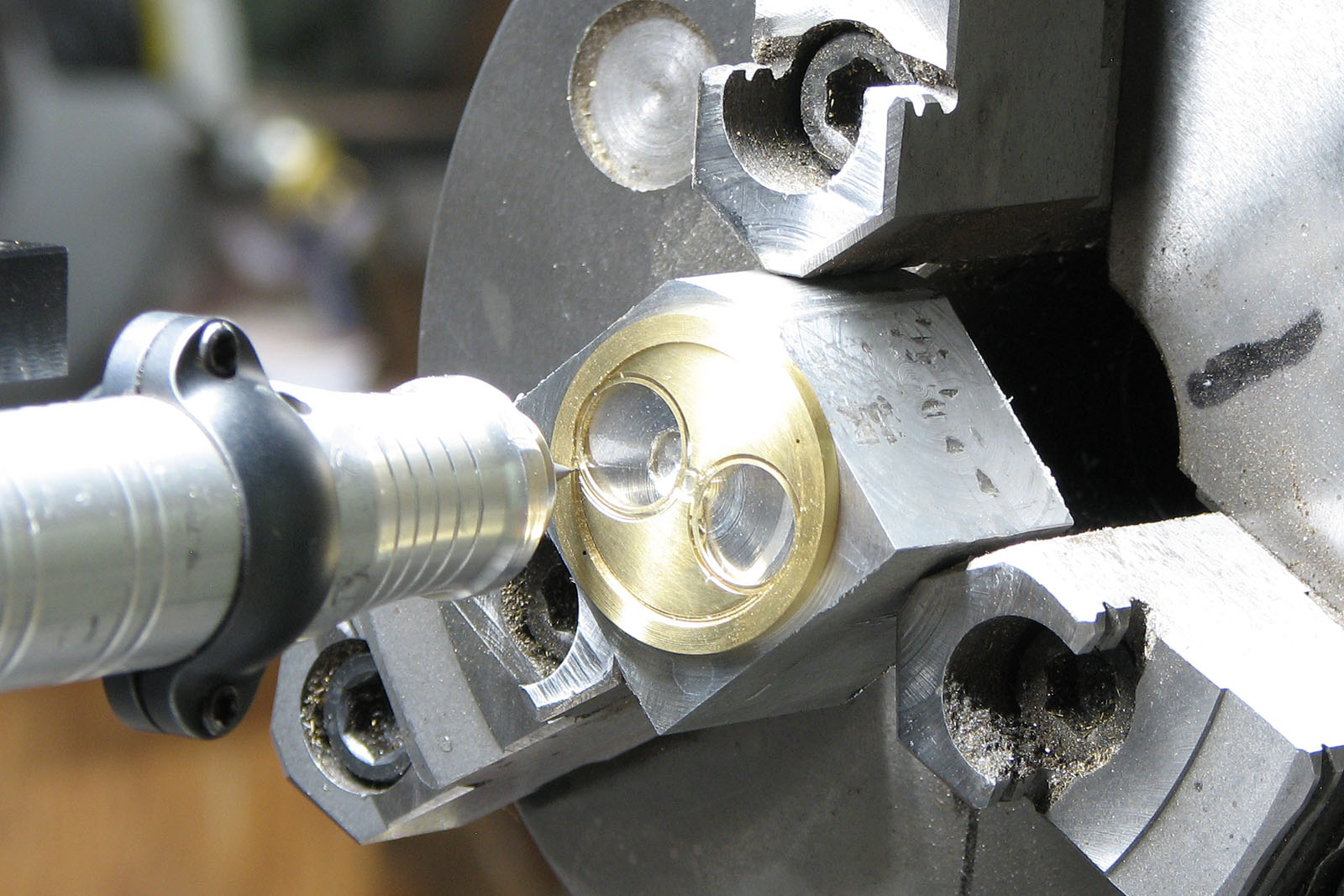

Milling the dial pieces from a brass blank.

The pieces which make up the dial.

Making of the hands; maybe also bluing them would have been a better design choice.

While the dial may feel like an afterthought, the visible jumping hour mechanism more than makes up for it. Under the dial sits the jump hour works based on the star wheels and springs. Such mechanisms usually employ a snail cam and follower for a crisp jump.

Here, Mr. Vicknair went for a simpler but satisfying star wheel mechanism. A finger mounted on the centre pinion (which also carries the minute hand) engages the first star wheel, which in turn engages a second star wheel carrying the hours hand.

Completed jump works.

The intermediate star wheel is kept secure by a large spring, which helps it snap when indexed to a new position. The snap is transmitted to the second star wheel, making for a swift change of hour.

The delicate finger and cannon pinion assembly.

Making of the jump works supporting bridge; The base Omega plate was substantially modified to accommodate the system.

Pivoting the star wheel.

The case

The simple case suits the watch very well, since the movement remains the centrepiece.

Mr. Vicknair crafted the case in the same spirit as the rest of the watch, starting from a steel ingot and carefully shaping the Calatrava-style case.The finishing on the case is tidy and leans heavily on polished surfaces.

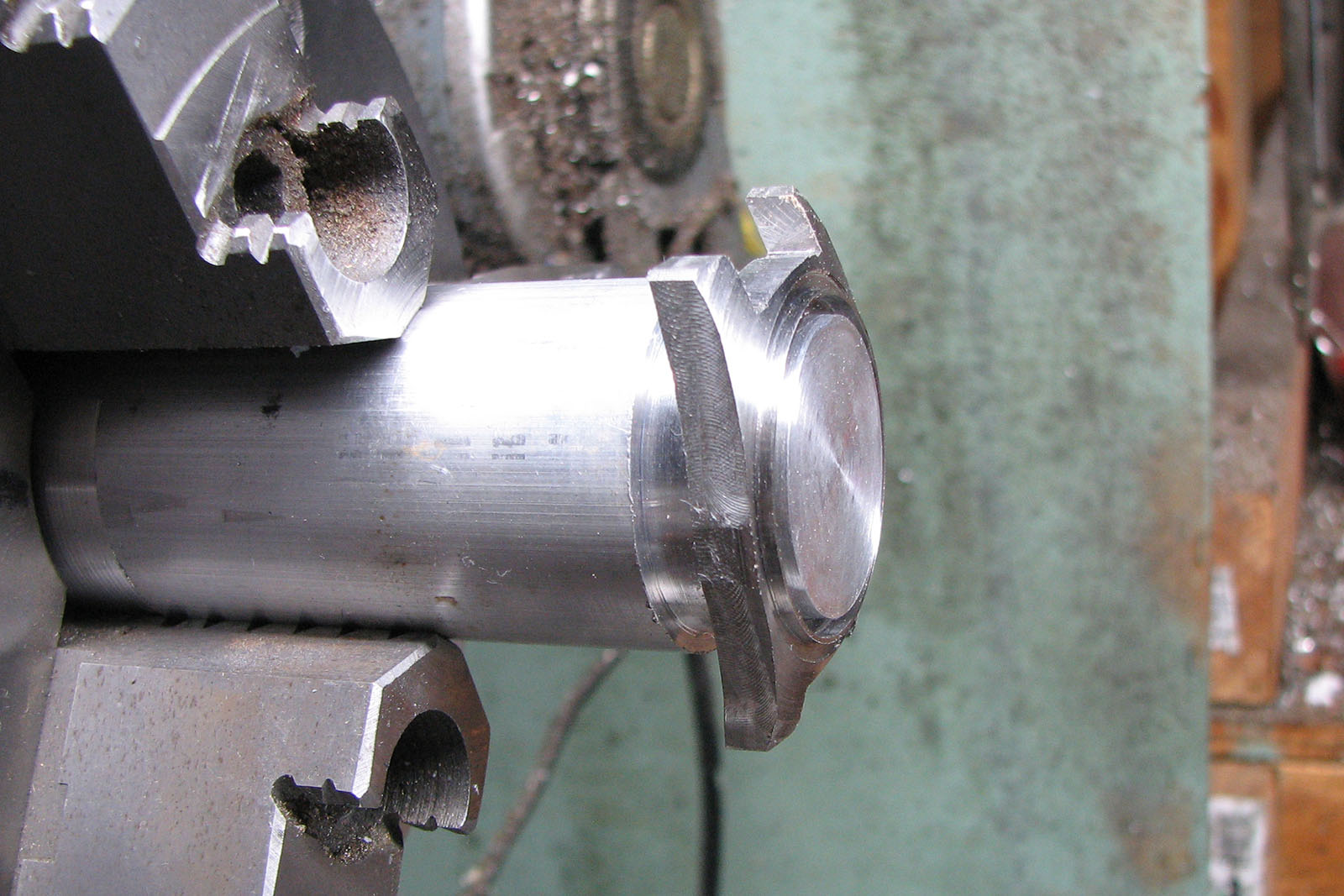

Early stages of case machining.

The case starts taking shape.

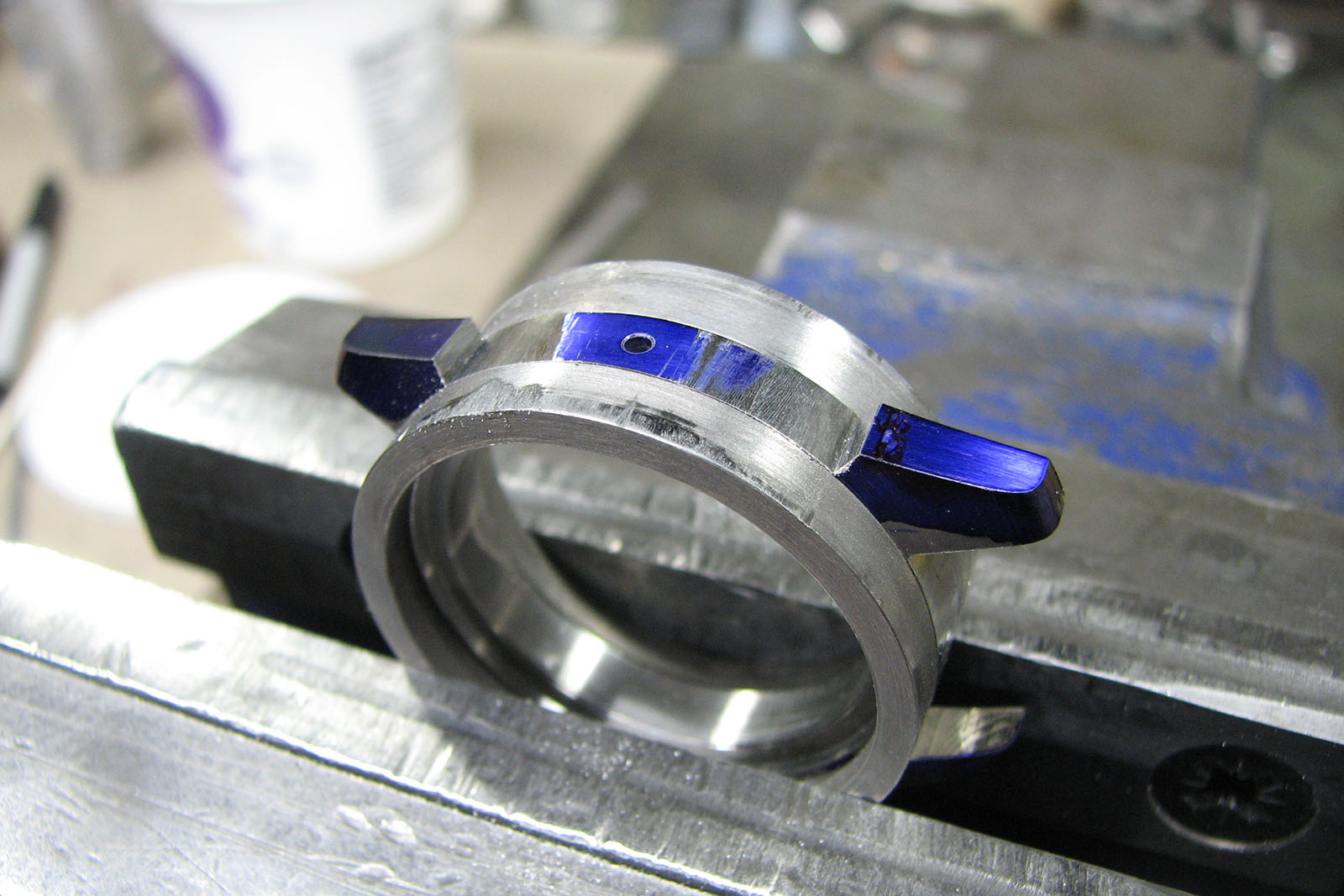

The lugs are to be slimmed down.

Finally, the cased watch with a tidy and clean caseback.

Key facts and price

Dewey Vicknair Handmade Wristwatch #2

Diameter: 38.5 mm

Height: 12 mm

Material: Stainless steel

Crystal: Sapphire

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: Based on Omega cal. 266

Functions: Jumping hours, minutes, and seconds on regulator-style display

Winding: Manual wind

Frequency: 18,000 beats per hour (2.5 Hz)

Power reserve: 35 hours

Strap: Calf-skin leather

Limited edition: Made to order

Availability: Direct from Mr Vicknair with a lead time of one year

Price: —

All images courtesy of Dewey Vicknair. For more, contact Mr Vicknair at Vicknairrestorations.com.

Back to top.