Guilloche for Beginners: A Photo Essay

Learning from the best.

Tucked away on a wooded island in the Pacific Northwest lies one of the most important horological workshops in the United States. Known as Memoria Technica, the workshop is owned by Brittany Nicole “Nico” Cox, a renowned conservator of mechanical objects.

I was first introduced to Nico in 2019 by Joshua Shapiro, the California-based watchmaker and guillocheur behind J.N. Shapiro. Joshua and I happened to visit Nico’s workshop on a day when she was teaching a beginner’s course on the art of guilloche. Since that encounter, I’d always had it in mind to return and take her class, but life (and a global pandemic) got in the way until I was finally able to secure a spot in her July class this year.

But what is guilloche? Within the context of decorative techniques, guilloche, also known as engine turning, occupies a niche all its own. Characterised by intricate, recurring, and overlapping patterns, guilloche techniques have been used to decorate some of the most coveted objects in history.

Meet your instructor

In the rarified world of antiquarian horology, Nico is practically a household name – a bit like Beyonce. Nico specialises in the conservation and restoration of all types of mechanical objects, from watches and clocks to music boxes and automata.

Having trained as a conservator at the Museum Speelklok in the Netherlands, which houses one of the world’s largest collections of mechanical musical objects, Nico is especially passionate about automata. Not only has she restored rare objects like this Bruguier “Singing Bird” box for the Toledo Museum of Art, but she has also created her own automata in-house.

Nico Cox. Image – Nico Cox/Making Time

In addition to the standard watchmaker certifications like WOSTEP and SAWTA, Nico has also earned a Masters degree in the Conservation of Clocks and Related Dynamic Objects from West Dean College in the United Kingdom.

Nico’s work has gained more widespread attention in recent years thanks to two feature-length documentaries about watchmaking, Keeper of Time and Making Time, in which she was featured alongside Philippe Dufour, Roger W. Smith, François-Paul Journe, Max Büsser, Ludovic Ballouard, and other familiar names from the world of independent watchmaking.

Day 1: The adventure begins

Boarding the ferry

Nico’s workshop is located on an island in Puget Sound and requires a short ferry from the mainland. Nestled amongst dense forests and green meadows, the setting is not unlike the Vallee de Joux, the heart of watchmaking in Switzerland. The workshop is full of antique watchmaking equipment that Nico has amassed throughout her career.

The workshop

With these priceless machines, Nico is able to craft wheels, pinions, and other components from scratch using the same methods that would have been used 150 years ago, enhancing the quality of her conservation work. Many of the objects she receives for restoration contain missing or damaged parts, so her ability to make these components is critical.

After greeting Nico, I met the other three students, two of whom (like me) have day jobs in the software industry in Seattle. I’d assumed that anyone taking a guilloche class would be deep down the rabbit hole of watches, but that was a flawed assumption.

Guilloche is an expansive art that touches many aspects of craft beyond watchmaking, and the other students were interested in craft techniques in general, and had experience in woodworking, jewellery making, photography, and other artistic skills. Unsurprisingly, these backgrounds served them well and they excelled throughout the class.

When the clock struck nine, we sat down for orientation. This consisted of a presentation about the history of engine turning, which dates to around 1540, almost 250 years before Abraham-Louis Breguet popularised its use for decorating watch dials.

The presentation was eye-opening. As a watch collector and enthusiast, my prior exposure to guilloche had been confined to that narrow context. But guilloche techniques have been used to decorate everything from the famous Fabergé Imperial Easter eggs to ornamental drinkware and even common household appliances.

The variety of designs that are possible with these techniques far exceeds what is actually practised by contemporary watch brands, and the workshop library has several books full of different designs and patterns, with information about how to make them.

The Gatchina Palace Egg by Fabergé is decorated with a moiré guilloche, covered by translucent enamel. Image – The Walters Art Museum

Examples of guilloche patterns. All of these designs were made using the same 24-bump rosette, but the patterns are different because of the adjustments made between cuts. Image – Nico Cox

Getting to know the machines

Once we had each selected a pattern to try, Nico introduced us to the machines, specifically the rose and straight line engines. For the beginner classes, Nico sets up the machines and chucks (the clamp-like attachments that hold the dial blanks) accordingly. For watchmakers who spend all day doing this kind of work, special microscopes are installed on the machines to provide a better view of the work surface.

But for the beginner course, we needed to have an unobstructed view of the machines to learn their secrets. Likewise, Nico had taken a few precautions before handing the machines over to us, such as installing chucks that are reserved for the beginner courses (and have the scratches and gouges to prove it).

This beautiful straight line engine is almost 100 years old

These precautions did not hinder us in any way, and we were grateful to have a little margin for safety; none of us wanted to risk damaging the rare machines. Nico’s passion is restoration and bringing life back to ancient objects. This includes the machines themselves, and she feels a responsibility to ensure that they remain functional for generations to come.

The rose engine

I started on the rose engine, and chose a barleycorn pattern – a relatively simple pattern that requires just one phase adjustment between each cut. This first experience was surprising in a number of ways.

For one thing, I’d always imagined that using a rose engine would be like playing a musical instrument, like a violin, and that the quality of the end result would depend primarily on the dexterity and sensitivity of my fingers on the slide rest that controls the cutter.

In his book Watchmaking, which was required reading for the class, George Daniels noted “A constant pressure on the slide is by far the most difficult skill to acquire in engine-turning and upon it depends the whole visual quality of the work.”

The rose engine

However, after the first few cuts I realised that the machine seemed to be doing a lot of work to compensate for my inexperienced touch, and my violin analogy was flawed. Instead, I would describe the process more like operating a camera in manual mode. Assuming you make all the necessary adjustments before each picture (or cut), you can achieve acceptable, repeatable results quite easily, even as a beginner.

My first attempt with the rose engine

But that’s easier said than done. Each pattern has a different ‘recipe’ of adjustments that need to be made before each and every cut, and the operator has to keep track of every step. Some of the adjustments seemed counterintuitive at first, and I made numerous mistakes that are evident in some of the patterns I created.

The Incan sun motif

For my second turn on the rose engine, I attempted a type of loose moiré pattern known as an Incan sun. The moiré pattern is fairly straightforward in principle, requiring just two adjustments between each cut. But one of these adjustments involves turning an adjustment screw known as “the worm” anywhere from zero to 20 clicks when phasing between cuts.

The moiré pattern emerging

Next up, I wanted to try another moiré pattern, with tighter spacing than the Incan sun motif. It’s an enjoyable, almost melodic process to create this design, and I was pleased with how it turned out. In terms of the ratio of skill needed to produce a visually appealing outcome, the moiré pattern is a good option for beginners, assuming one follows the instructions to the letter.

The recipe card for the adjustments needed between each cut to produce the moiré pattern

As the first day of instruction drew to a close, my eyes wandered to the framed portraits of watchmaking greats that adorned the walls. Breguet, Graham, Earshaw, Frodsham, Huygens, and others gazed back. Nico lamented that she doesn’t have portraits of her personal heroes like Jacob Frisard and James Cox, 18th century horologists who were known for their automata, simply because no known images of these men survive.

I took away several insights from the first day of class that will stay with me, and that have enhanced my appreciation for the craft. The first is the incredible history of engine turning, and the rich diversity of patterns that can be produced using just two machines. It’s truly incredible to see what these artisan engineers have come up with over the past 400 years.

The second is the difficult nature of the work. Not difficult in the way I’d expected, but in the challenging combination of learning to unlock the secrets of a complex machine while simultaneously cultivating steady control and delicacy of touch. In other words, the work is challenging both intellectually and physically.

It’s also stressful! Approaching the end of a complex pattern, the pressure mounts to not make a mistake that ruins the last hour (or more) of work. Upon completing each pattern, I breathed a huge sigh of relief.

The ratchet, which moves the cutter in horizontal increments between each cut, produces a very satisfying click clack sound

Finally, I was struck by the peaceful nature of the work. Once I found a good rhythm and got used to the sequence of operations, the comforting repetition and tactile feedback from the machines (especially the “cliiiiick clack“ of the ratchet) put me in an almost meditative state. Watching the cutter bite into the metal and seeing a pattern slowly emerge is extremely satisfying, and I can imagine it becomes quite addictive. In the days since the class, I’ve actually dreamt of this aspect of the work more than once.

Day 2: Making progress

Our scope expanded on day two, and we started out by sharpening the cutter. Holding the tip of the cutter against a spinning wheel, we applied a 10-degree angle to the cutting face. Known fondly as a Daniels cutter in honour of George Daniels, the 10-degree facet results in a shallower cutting face than those used in jewellery making, which can vary from 12 degrees all the way up to 30 degrees. As you might expect, the Daniels cutter is best suited for the depths of cuts needed to produce patterns that look good on something the size of a watch dial.

Applying the 10 degree “Daniels” angle to the cutter

The straight line engine

Having gained some good experience on the rose engine, it was time to try my hand at the straight line engine. I naively thought this would be easier than the rose engine, but I was wrong. For one thing, the geometric nature of straight line patterns makes it easier to spot tiny mistakes that would otherwise disappear in a circular pattern. Furthermore, straight line patterns require the operator to be more careful when beginning and ending each cut.

The straight line engine

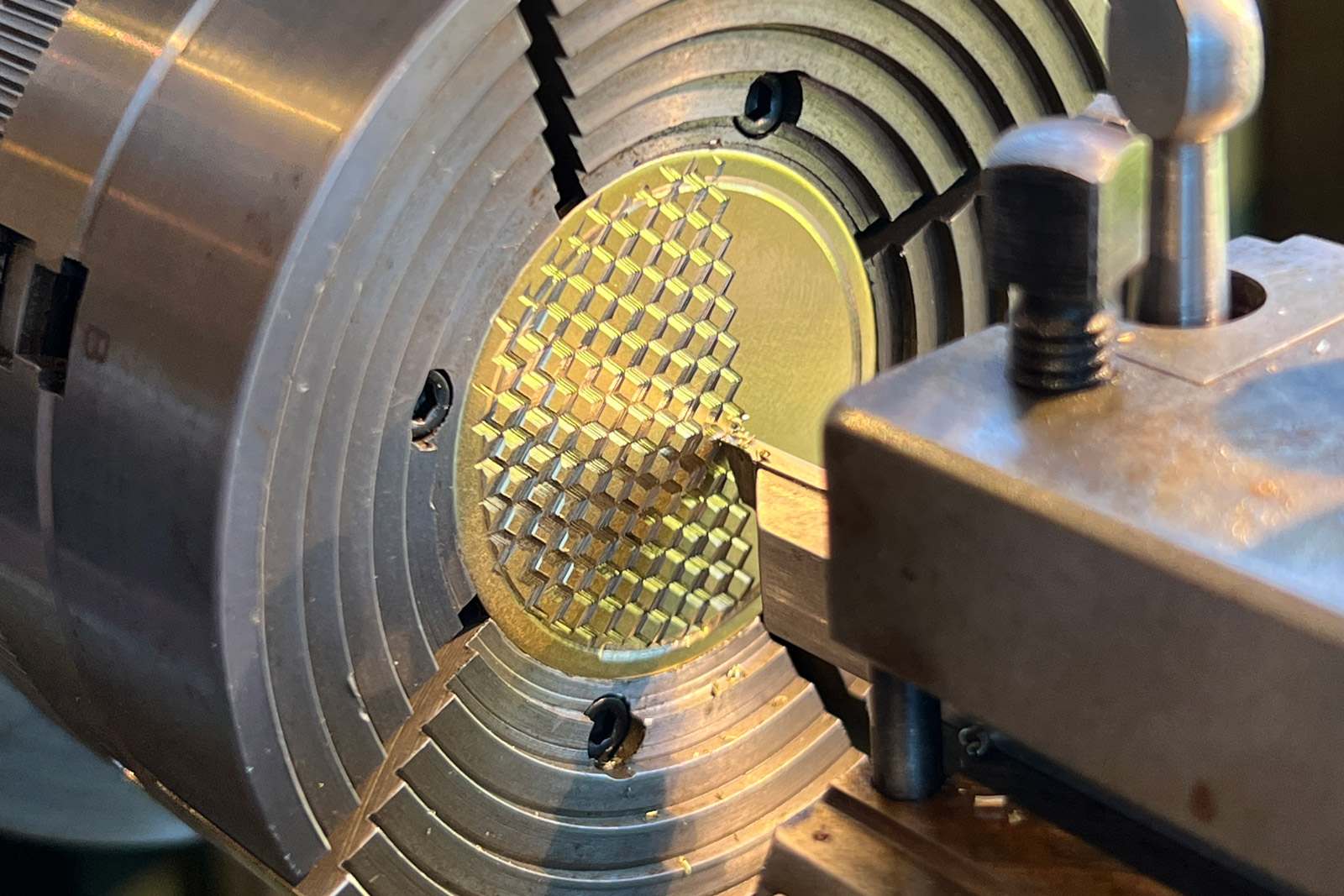

The cubic pattern in progress

For the straight line engine, I wanted to try a geometric cubic pattern, like that used on the Louis Erard Excellence Guilloché Main. I’ve always liked this pattern for the M.C. Escher-esque optical illusion that it creates when done well. I didn’t execute it perfectly, but in the process I became much more comfortable with the eccentricities of the straight line engine; experience that proved helpful for the complicated honeycomb pattern I attempted next.

The pattern bars that are used for the honeycomb pattern

I’ve always appreciated Chopard’s honeycomb guilloche, and selected a similar hexagonal pattern to try on the straight line engine. This pattern took a few tries for me to get right, as it requires switching between pattern bars and adjusting the offset every few cuts.

On the first two attempts I made mistakes in the sequence of operations, causing the end result to look more like a chaotic circuit board than the honeycomb pattern I’d been trying to produce. I was inclined to switch to an easier pattern, but Nico encouraged me to keep going and even annotated the instructions to make it easier for me to stay on track.

The third time was the charm, and though I strayed outside the lines a bit, overall I was thrilled with the result.

The honeycomb pattern finally taking shape on my third attempt

Simplicity = difficulty

A big takeaway from the class is the relative difficulty of the various patterns. I’d never thought this through, but I had always assumed that the complex circular patterns would be the most difficult to create, and that straightforward patterns like Clous de Paris (also known as hobnail) would be the easiest.

In fact, simpler geometric patterns leave no room to hide mistakes, making Clous de Paris is among the most challenging patterns to do well on a large surface. Any variance in pressure on the cutter will be immediately obvious, because it will catch the light differently than the surrounding area. In other words, the simpler the pattern, the more precision is required both in the setup of the machine and the sensitivity of the operator’s touch.

To experience this firsthand, I used my last turn on the straight line engine to create a Clous de Paris pattern. I wanted to try this simple pattern to get a sense of how much delicacy is needed to execute it perfectly. As expected, I found it to be quite challenging. I was only able to produce an even surface on a small section of the dial, enhancing my respect for makers that can apply this pattern flawlessly to a large dial surface.

My attempt at the challenging Clous de Paris pattern resulted in an uneven surface

Of course, it’s more challenging still to produce dials that feature multiple patterns on the same surface. It requires a delicate touch to start and stop each cut in exactly the right place. While this is covered in greater detail in Nico’s advanced course, a couple of the other students experimented with combining different patterns. It’s stressful work because a single mistake can potentially ruin both patterns.

Concluding thoughts

On the ferry back to Seattle, I reflected on how true, hand-turned guilloche fits into the contemporary watchmaking landscape. The artisanal nature of the work makes it difficult to scale, lending an inherent, natural exclusivity to watches with guilloche dials. This constraint is problematic for brands that are targeting certain volumes or price points.

Very happy with the outcome of the honeycomb and moiré patterns

As a result, many brands have sought workarounds to these constraints. Stamped guilloche is increasingly common, even from brands like Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet. During the class, I was surprised to learn that stamped guilloche actually has a long history as a decorative technique for consumer products like household appliances and personal care items. But after seeing a stamped guilloche pattern on a plastic hand mirror during orientation, I would find it difficult to accept this technique on the dial of a haute horlogerie watch.

Mt. Rainier looming over Puget Sound on my ferry ride home

In addition, there are a small number of brands and independent specialists that are creating guilloche patterns using CNC machines – essentially an automated engraving process – with seemingly good results. Compared to stamping, this technique better captures the look of hand-turned guilloche. To the extent that these techniques open the door to new possibilities for patterns, I’d argue they are a welcome development.

That said, a big part of what makes guilloche work so special is the connection it forms between the viewer and the artist who created it. In the same way that an original painting differs from a printed copy, a hand-turned dial exudes a distinct allure and sense of intimacy that is absent from machine-made copies.

Back to top.