Memento Mori – The Vivid Life of the Skull Watch

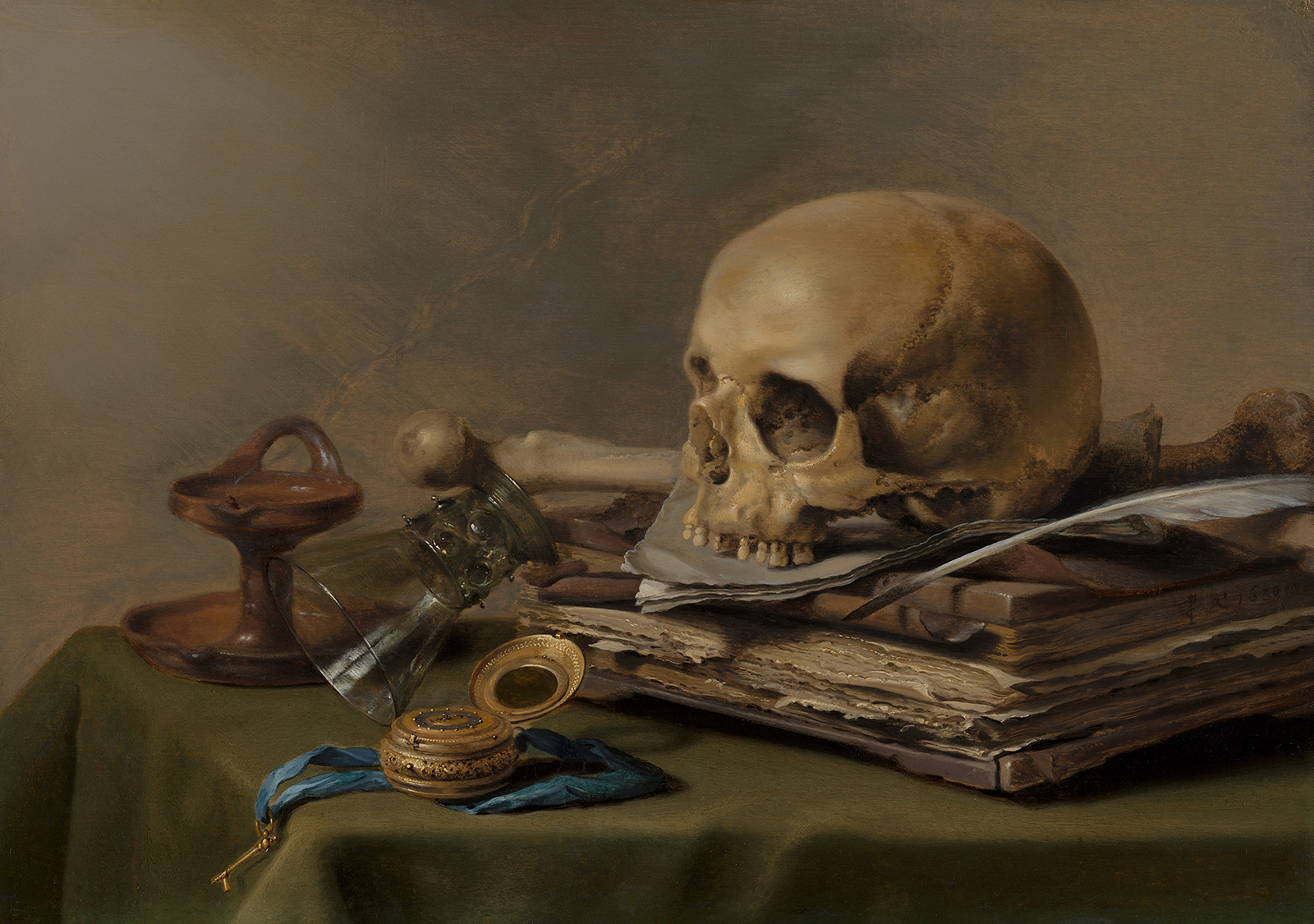

A macabre art form that inspired horology.

While the invention of the pocket watch in the 16th century brought reasonably exact time measurement into the daily life of those who could afford such timekeepers, it also cultivated a deeper awareness of the brevity of life amongst the broader population. Striking mechanisms were added to watches for practical purposes, and presumably to remind the wearer of time’s passage. That notion was later to gain tangible form with the creation of skull watches, embodying the idea that death drew closer with each passing tick.

Skull watches were in a sense futile, since life in the medieval Europe was brutish and short, averaging just 40 years. Disease was common, but none more famous than the plague pandemic of the 14th century, with recurrent outbreaks persisting for the next 400 years.

That misery was compounded by ceaseless conflict. The great powers of the day, France and England, fought over the French throne in a series of long, deadly wars, known collectively as the Hundred Years’ War. And this was also a time when the Catholic Church itself, possessed of both wealth and influence, became a contested turf, resulting in endless religious conflict and political unrest.

Pogrom of Strasbourg (1349) by Emile Schweitzer

The frequency of death heightened the desire for penance, propelled by the beliefs of medieval Christianity. Paramount to spiritual health was the recognition of time as not just a unit of measurement but also a mode of temporality, and that though death must come for all, it was an individual experience, not a collective one. Naturally, this realisation soon shaped societal values such as integrity, virtue and salvation, deemed necessary in order to be received into the kingdom of God. The printed material bestseller lists reflected that: the Ars moriendi, Latin scriptures on the art of dying well, were popular reads during the period. Thus, the practice of reflection on one’s mortality, memento mori, Latin for “remember you have to die”, grew to become a popular penitential discipline that inspired art, music, literature, and eventually, horology.

Latin texts of Ars Moriendi included instructions on deathbed procedure and prayers, as well as the five temptations of the Devil that a dying person will face. (Image: Staatsbibliothek Bamberg.)

Raymond Champenois (d.1678) Paris, c.1670 (Image:The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.)

Skull-shaped watches, a metonymic symbol of memento mori soon became fashionable in Reformation Europe, particularly in Blois, the center of Protestantism in France, as well as in Calvinist Geneva. The small Swiss city was a beneficiary of the fleeing diaspora as many French Protestant watchmakers flocked there seeking refuge after the Catholic King Louis XIV rescinded the right to religious freedom in 1685 with the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

A silver verge watch with a fusee and chain by J C Vuolf, German (1655-1665). (Image: the British Museum)

A silver skull watch made by Isaac Penard, Swiss (1619–1676) with a case produced by the Firm of Moulinié, Bautte & Moynier (Swiss, 1808–21). (Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Mary, Queen of Scots

One of the most significant skull watches of the period purportedly belonged to Mary, Queen of Scots, who commissioned several such watches during her lifetime. It was an elaborately engraved silver skull watch made by French watchmaker J. Moysan of Blois. It was covered with scenes depicting various biblical events: the fall of Adam and Eve – whose crime was the cause of labour and death on earth – the salvation of man, the Crucifixion, and time devouring all things. Each tableau was accompanied by verses from the poet Horace. Engraved on the forehead of the skull was a skeletal figure of Death with his scythe in one hand and an hourglass in another. The hinged jaw of the skull opened to reveal the movement inside that had a small hammer to strike the hours.

The gruesome tales surrounding the watch, however, are dubious at best, with a popular account suggesting that before Queen Mary was beheaded for treason in 1587 at the order of her cousin Elizabeth I, she gave the watch to one of her ladies-in-waiting. Another apocryphal tale propounds that it was given away during the period of mourning after the death of her first husband, King Francis II of France. As with well-worn stories from centuries ago, it is difficult to distinguish fact from fiction, but the lurid image of Mary spending her final days pondering the hollow eyes of her skull watch is matched only by her actual beheading, which took a particularly inept executioner a horrifying three strokes to complete.

Today, the skull has been appropriated by myriad constiuencies for varying purposes, becoming a part of pop culture. Youth and street culture has taken it as an emblems of defiance rather than dread, and so have biker gangs as well as a series of musical genres, from punk to heavy metal and death metal. And as with so many other pop culture motifs, the skull has become something expensive, to a point of being emptied of its meaning. It’s found on the fashions of Alexander McQueen, whose skull scarves were sold out all over the world after his suicide, to the ungraceful clothing of Philipp Plein. And then there’s the diamond-encrusted sculpture by Damien Hirst, which has a nine figure price tag even a Queen would struggle to stomach. Where contemporary art and fashion go, so does modern watchmaking.

Bell & Ross

An unlikely but nevertheless striking series of skull watches come from the French maker of aviation-inspired timepieces, Bell & Ross. They adopted the skull and crossbones, better known as the Jolly Roger, which emerged during the golden age of piracy. As life on the high seas brought together pirates from far and wide who spoke different tongues, the Jolly Roger became the uniform symbol that transcended national origin and united them. The skull motif was also used to strike fear in the heart of the ships they pursued, sometimes pillaging for the state and at other times for personal gain.

Bell & Ross took its most famous watch case, the square BR 01, and fitted it with a skull-shaped dial and bezel. The idea spawned various iterations, including a bejewelled skull, another in greenish patinated bronze, as well as a fabulous engraved version that lassoed in tattooing, yet another martial tradition.

Richard Mille

With cost comes notoriety, and at the stratospheric end of the spectrum is the half-million dollar RM 052 Skull Tourbillon from Richard Mille, perhaps the perfect horological complement to Philipp Plein’s clothing. Richard Mille took the skull watch to the next logical (and pun-inflected) step: skeletonisation. Not merely a skull inlay, the open-working was smartly integrated into the movement.

The watch has a skull-shaped base plate made of titanium, with a pair of crossbones that serve as bridges. Interestingly, the skull has its mouth slightly agape to reveal the cap jewel of the tourbillon, giving the impression that it is about to devour time.

HYT

Another unexpected brand to ride on the coattails of the skull’s modern-day preponderance is the maker of fluid-filled watches, HYT. Unlike the most of its timepieces that have a circular glass capillary to indicate the hours, the HYT Skull has it shaped with eight bends to form the outline of a skull. The right eye of the skull displays the power reserve indicator while the other eye contains the constant seconds.

The design has lent itself to various iterations with the more memorable ones being the Skull Maori which features a skull hand-engraved with a Maori tribal tattoo, and also the Skull Pocket that has a hunter case. The lid opens to reveal a faceted skull with a dynamo-powered light that illuminates the dial, charged and activated via the pusher at five o’clock.

Corum

At Baselworld 2018 Corum has revived its classic Coin watch and put a modern spin on it. The Heritage Artisan Coin Watch showcases the coin engraving work of New York-based Russian artist Aleksey Saburov, who is part of the thriving community of contemporary hobo nickel engravers.

Deeply rooted in American culture, the “hobo nickel” is an engraved small denomination coin, an art form that emerged during the Great Depression. They were so dubbed because they were borne of creatively economical hobos who would fashion classic Buffalo nickels with whimsical designs to make a miserly profit.

Each Corum Hobo Coin Watch features a certain depiction of a skull, micro-engraved on a U.S. silver dollar. The coin is split, with the two halves sandwiching the movement; one half forms the dial and the other the case back. It is housed in a 43mm silver case with a sapphire-tipped crown and a bezel that is fluted to mimic the edge of a coin. The watch fitted with a denim strap, another emblem of pop culture, and is powered by the automatic cal. CO 082, which is based on the ETA 2892.

CLVII Paris

Nowhere is the appropriation of skull motifs more widespread than in contemporary streetwear. High-end French label, CLVII, named after its location – 157 rue du Faubourg Saint Honoré – was set up in 2007 and has dressed athletes like football player Didier Drogba, as well as musicians like Lil’ Wayne and Jason Derulo.

CLVII recently launched its first watch collection featuring its founder’s signature, and decidedly hedonistic, intepretation of momento mori – a toothy skull wearing a pair of retro aviator shades. The case is made of stainless steel with either an aged or rose gold finish, and houses an automatic Seiko Epson NH35 movement, fittingly inexpensive for a watch of an inherently temporal nature.

Back to top.