Explaining the Greubel Forsey Quantième Perpétuel à Équation

Complicated but simple.

Greubel Forsey doesn’t make simple watches. Its twin time zone GMT wristwatch, for instance, takes the travel time complication to another level. Similarly, the Quantième Perpétuel à Équationis no ordinary perpetual calendar. It features a full calendar with leap year and four digit year display, equation of time with seasons, solstices and equinoxes indicators – with all functions set via the crown.

The movement is made up of 570 parts, a high count even for a watch this complicated. In comparison, the Patek Philippe calibre R TO 27 PS QR – featuring a perpetual, tourbillon and minute repeater – found in the Grand Complication Ref. 5016 comprises 506 components.

Tourbillon 24-seconde

The constant feature of every Greubel Forsey timepiece (with one exception) is a tourbillon regulator. The perpetual calendar is equipped with the brand’s simplest – the same tourbillon found in its entry-level wristwatch – a high speed tourbillon that makes one revolution every 24 seconds, instead of the conventional one minute. And the tourbillon is inclined at 25° to the plane of the movement.

The high speed and incline were both devised to average out gravitational errors on the wrist. Because the wrist is constantly moving, the position of the balance is constantly shifting, so a standard tourbillon is less adept at counteracting the effects of gravity.

A fuss-free perpetual calendar

The key indications of the perpetual are found on the sub-dial at five o’clock, with the day, date and month in windows. Just to its left is the leap year indicator, and at seven o’clock is the 24-hour display. That’s not for a second time zone, rather it shows in red the hours around midnight when the calendar is changing and cannot be set. A safety mechanism disengages the setting mechanism during that period.

|

| The skeleton hour and minute hands are white gold |

All the indications of the perpetual calendar are set via the crown, backwards and forwards. This is the most straightforward method for setting a perpetual calendar, since it eliminates the multiple pushers for individual calendar functions that are found in conventional perpetuals. However, the downside of such a system is the need to scroll through multiple dates and months if the current date is far from the calendar display.

The crown has a co-axial button as a crown function selector. Pressing the button allows the crown to be used to set the time or the perpetual calendar. The two tiny windows at two o’clock indicate which function has been selected – “QP” for quantième perpétuel and “HM” for heures en minutes. Because the perpetual calendar is controlled by a stack of gears that form a tiny column, the calendar displays are continued on the back in the same relative position as those on the front.

|

| The bridges are made of German silver |

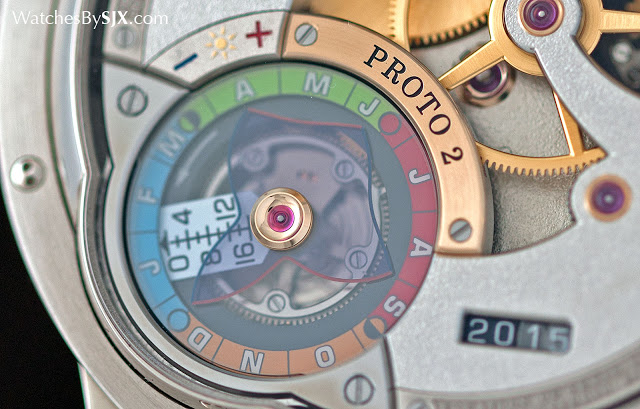

A multicoloured sub-dial indicates the equation of time, four seasons, solstices and equinoxes. Because the sub-dial is clear sapphire, some of the gears of the calendar mechanism are visible below. And the year is displayed in four digits in a small window (making this one of the few watches with this feature that IWC pioneered).

The equation of time

The rectangular, white plate with an arrow at its edge points to the month and season. Blue, for example, indicates winter, with each month represented by its first letter. The numbers on the rectangular plate reading from 0 to 16 is the equation of time display, read via the manta ray-shaped indicator on the sapphire disc. The red lines of the manta ray indicate that apparent solar time (the time according to the Earth’s orbit around the Sun) is running ahead of mean solar time (the 24-hour day shown on a watch).

If apparent solar time is behind mean solar time, it’s indicated by the blue lines of the manta ray. The photo above shows that apparent solar time is behind mean solar time by 12 minutes, so the actual length of the day is 12 minutes less than 24 hours. The difference stems from the fact that the Earth orbits the Sun in an ellipse, while the 24-hour day approximates a circular orbit.

Equinoxes and solstices are also indicated on the sapphire disc, but are missing from this pictured prototype.

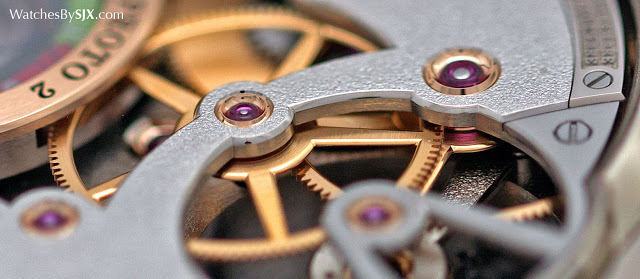

Finishing

As is typical of Greubel Forsey, the movement is lavishly and expensively decorated. The appearance of the movement is characteristic of the brand, with the bridges finished in a fine frosting, large jewels in gold chatons and wide, polished bevels on the edges of the bridges. The quality and finesse of the finishing is one reason why Greubel Forsey watches are expensive.

|

| The black polished V-shaped tourbillon bridge |

|

| Note the obvious chamfering of the spokes and centre of the gear |

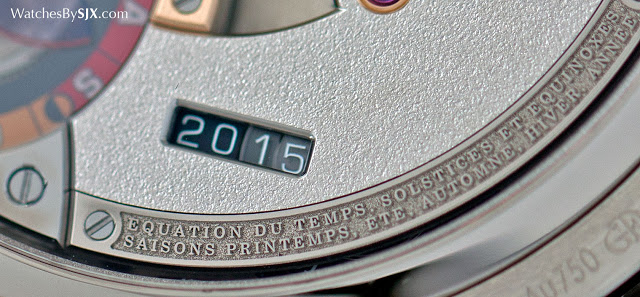

And both rims of the bridge feature plaques made of solid gold covered with minuscule text, rendered in relief. This tiny lettering is engraved by laser, then polished by hand. Common to several Greubel Forsey watches, and sometimes even found on the watch case, the text on the perpetual calendar explains the functions of the movement as well as the equinoxes and solstices. The top line of text shown below translates as “Equinoxe between 19 and 21 March, then between 21 and 24 September”.

Like the rest of Greubel Forsey’s watches, the Quantième Perpétuel à Équation is a large watch, measuring 43.5mm in diameter and 16mm high. The case is white gold.

Limited in production to a handful each year, the Quantième Perpétuel à Équation is priced at SFr670,000 before taxes, equivalent to US$692,000.

Back to top.