Hugues’ Accomplishment: The Story of Hugues Bürki

From chronometry champion to chronograph innovator.

Nestled in the Jura Mountains, La Chaux-de-Fonds has been a cradle of Swiss watchmaking ever since its watchmaking school, the Technicum, opened in 1865. For aspiring watchmakers, the climax of their training was traditionally the creation of a montre école – or what’s known as a school watch.

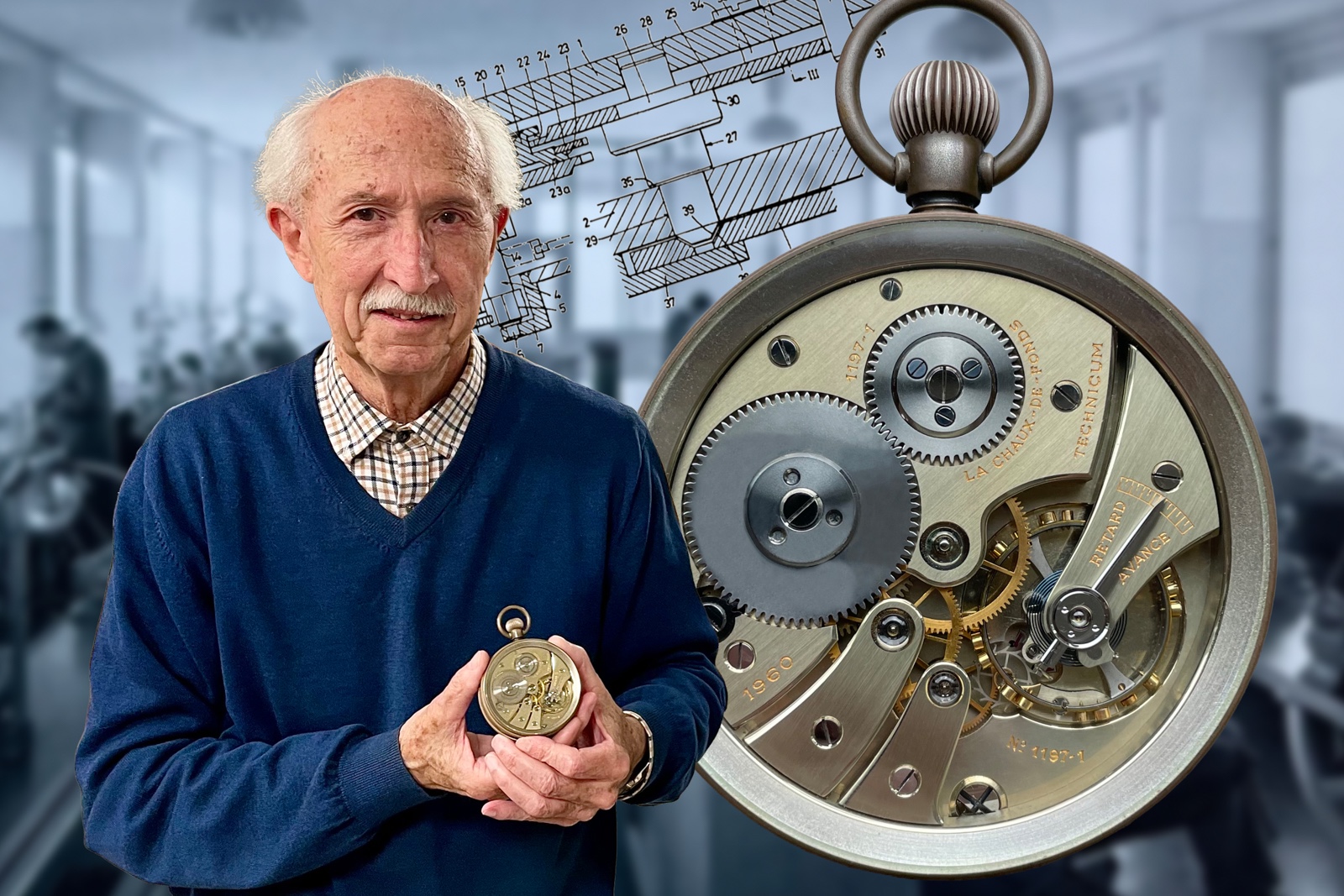

This is the story of Hugues Bürki, a Technicum alumnus, who built what would become a record-breaking school watch, and who would later make horological history as a movement engineer.

Hugues Bürki. Image – author

The Technicum

The watchmaking school of La Chaux-de-Fonds was founded in 1865. In its early days, the school occupied rooms inside the modestly named ‘Technicum’, a local vocational-technical school. By 1885, the school’s own building had been inaugurated, yet the name Technicum stuck. In 1933, in the wake of the global economic crisis, the nearby watchmaking schools in La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle were merged to form the Technicum Neuchâtelois.

The Technicum in the 1960s. Image – author

It demands attention that both divisions of the Technicum Neuchâtelois had a particularly strong focus on high-precision chronometry at the time compared to other watchmaking schools in Switzerland, which specialised in other domains, such as the construction of complications and traditional finishing techniques. In fact, some of the innovations in chronometry we associate with brands like Longines can actually trace their roots to the Technicum Neuchâtelois, including the use of a non-round calibre to maximize the available space for the balance wheel and mainspring barrel. The first such calibre to compete in Neuchâtel was developed by the Le Locle division, and was submitted in 1945 by André Jeanmairet, who was later appointed director of the school.

This academic focus mirrored the needs of local employers like Le Locle-based Ulysse Nardin that were engaged in the production of precision watches and marine chronometers. It was a student pipeline that worked. In 1922, for example, Ulysse Nardin swept the podium in the marine chronometer trials at the Washington Naval Observatory in the United States. The brand repeated its triumph the next year, taking 15 of the top 25 places overall.

The earliest known non-round wristwatch-sized calibre submitted for observatory testing, produced by the watchmaking school in Le Locle and adjusted for competition in 1945 by André Jeanmairet. Image – author

The chronometry-focused approach of both institutions is well illustrated by almost a century of continuous participation at the esteemed observatory competitions in the nearby city of Neuchâtel. According to the available archive material, the first Technicum school watch was tested at the observatory as early as 1883. In the years from 1923 to 1967, the Technicum Neuchâtelois contributed 90% of all submitted school watches at the observatory in Neuchâtel. The remaining 10% were submitted from the other eight watchmaking schools in Switzerland at that time.

Many alumni fondly recall the spirited rivalry between the two school divisions, La Chaux-de-Fonds vs. Le Locle; a rivalry that, in retrospect, reveals itself as the lifeblood of healthy competition. It was precisely this drive that propelled both schools to historic heights, elevating not only the quality of education but also their remarkable achievements in chronometry.

This environment was particularly fertile ground for horological ingenuity. Nine distinct school-developed calibres had emerged over the years out of the La Chaux-de-Fonds division, cementing a strong institutional reputation in precision watchmaking. Among them, and particularly noteworthy, are the cal. 65, a 65 mm board chronometer, and the cal. 49.9, which was the last complete calibre to originate from the bright minds of the Technicum.

Hugues Bürki’s cal. 65 school watch. Image – author

The calibre 65

Conceived in the early 1930s, the cal. 65 was developed in-school in its entirety and is not based on an externally sourced ébauche. This fact is crucial, since students at other watchmaking schools often relied on ébauches supplied by manufacturers like LeCoultre, IWC, Omega, Zenith or Patek Philippe, only performing the final steps of production themselves. In contrast, the cal. 65 had to be crafted from scratch by each respective student, according to technical blueprints provided during the first year of their training.

Technical drawings of the cal. 65. Image – author

Reserved for the most gifted, the construction of a cal. 65 was only assigned to students who had chosen to pursue the prestigious Technicien-Horloger track, a five-and-a-half-year programme devised in 1895 by Paul Berner, then-director of the Technicum. Positioned at the very top of the training hierarchy, it was a demanding curriculum designed to produce horological polymaths and forge the forefront of the Swiss watchmaking industry.

Trained in small groups of five to six pupils, the Techniciens-Horlogers were microengineers at the drawing board, machinists at the lathe, assemblers at the bench, and régleurs in the test room – capable of designing and constructing entire movements from scratch.

Rough plates and bridges for the cal. 65. Image – author

Only a select few managed to pull it off. From 1935 to 1970, only 76 school watches based on the cal. 65 were ever crafted. The movement’s plates and bridges were machined from maillechort, also known as German Silver, the storied cupronickel alloy favoured in traditional Neuchâtelois watchmaking. Encased in solid silver, the resulting timepieces were nothing short of monumental: a commanding 71 mm in diameter and tipping the scales at nearly half a kilo.

There are two versions of the cal. 65, distinguished mainly by the presence of an “up/down” power reserve indicator. In either format, the movement features a lowered and offset escape wheel cock to position the escape wheel under the balance wheel, closer to its axis, and to create space for an oversized balance wheel, which would then be limited only by the position of the centre wheel pivot.

This construction, also seen in several smaller wristwatch-sized observatory chronometers like the legendary Omega cal. 30GD, allows engineers to maximise the moment of inertia by using a larger balance wheel with more mass.

Hugues Bürki’s cal. 65 school watch. Image – author

Before the dawn of high-beat calibres like the Longines cal. 360, a slow-beat oscillator with a high moment of inertia was usually favoured for the static, laboratory-like testing conditions of the observatory. Although observatories later explored dynamic testing under accelerations, heat, shocks, and magnetic fields, these tests were never fully implemented. Had they been, engineers would likely have made different trade-offs in construction.

The pallet fork and escape wheel in the cal. 65 are kept as small and light as possible, minimising energy losses and further stabilising the oscillator. Naturally, given the chronometry-minded philosophy of the Technicum, no expense was spared on the oscillator itself, which featured both Grossmann inner and Phillips outer terminal curves on the hairspring to ensure concentric breathing and align the hairspring’s center of gravity as close to the balance axis as possible.

Key components of Mr Bürki’s cal. 65 school watch. Image – author

The cal. 65 also featured a Guillaume balance wheel with a brass outer and nickel-steel (Anibal) inner rim, a complex design capable of eliminating up to 90% of secondary temperature error. This design outperforms traditional bi-metallic balances and remained the standard in observatory chronometers long after the development of monometallic balances and Nivarox hairsprings. Temperature errors, both primary and secondary, played a crucial role in observatory rankings, making compensation critical.

Hugues Bürki’s cal. 65 school watch – note the markings at 25 and 35 on the small seconds sub-dial; these markings helped observatory staff take precise measurements. Image – author

The competitive landscape

In their heyday, the Neuchâtel Observatory trials (Le Concours Chronométrique) represented the apex of mechanical precision. Movements were tested for up to 45 days in multiple positions and temperatures, and entered in various classes depending on movement diameter and surface area.

For students, these trials were the ultimate proving ground, as success was a badge of both personal skill and institutional excellence. Their importance can be derived from the fact that the names of the freshly minted watchmakers and their observatory results appeared in public newspapers. Furthermore, the students who submitted the best-performing school watches received monetary prizes and industry-sponsored awards.

Contemporary news coverage of the observatory results.

The cal. 65, as well as its later replacement, the aforementioned cal. 49.9, had been a recurring participant, consistently earning honours and pushing the boundaries of what a student-made chronometer could achieve.

It needs to be acknowledged that although the students completed both basic and advanced courses in réglage, or fine adjustment, the watches submitted to the observatory received a final touch from the school’s maître du réglage de précision; the instructor tasked with passing down the art of fine adjustment.

At the Technicum, Mr Sautebin and later Mr Girardet applied decades of experience in adjusting the regulating organ, benefitting from a level of expertise (including special breathing techniques to maintain steady control) that six years of training alone could not provide.

Bürki’s triumph

In 1966, after four years of fabrication and one year of painstaking regulation, a student named Hugues Bürki submitted his cal. 65-based montre ecole to the Neuchâtel Observatory in the board-chronometer class, one of the competition’s two most stringent categories along with marine chronometers.

Watches that completed testing were given an N-score (shorthand for Nombre de Classement) that was calculated from the rate results over the 45-day testing period. An N-score of zero represented the theoretical ideal with no measurable deviation.

Performance certificates for Hugues Bürki’s cal. 65 school watch. Image – author

When testing was complete and the scores were tallied, Mr Bürki’s watch achieved an N-score of 3.31 points — the best score ever attained by a large-calibre school watch, conducted under the last valid rule set of 1952. A closer analysis of the score reveals a mean daily deviation of just 0.07 seconds; a level of precision nearly indistinguishable from that of quartz timekeeper.

To put this performance in perspective, cal. 65-based school watches yielded an all-time average N-score of 6.90, and even the finest chronometers from the industry often struggled to get below the 4.00 mark, as evidenced by the N-score progression chart published in the observatory’s annual report of 1966.

Even more remarkable, Mr Bürki’s record remains unbroken, having outlasted the the era of observatory competition. The image is vivid: a young horologist, at the end of an almost six-year odyssey, having fabricated every component, witnesses his movement setting a new precision record. It was a triumph born of steadfast dedication to a rigorous curriculum.

The N-score progression over time. Image – author

From chronometry champion to chronograph innovator

After graduation, Mr Bürki took his talents into the industry. He joined the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH) which had been formed in 1930 as a merger between Omega and Tissot. The group acquired Lemania in 1932, and by the time Mr Bürki joined the firm, Omega and Lemania were gearing up to build a next-generation automatic chronograph, and Mr Bürki was tasked with devising technical solutions. His inventive productivity is evident in the numerous patents that bear his name.

His chief contribution was a novel vertical friction clutch for chronographs. Up until that point, most chronographs were of the horizontal clutch variety — a traditional design that inherently suffers from a degree of backlash when starting due to the way the wheels of the chronograph train slide into mesh with those of the going train. While this effect can be minimised with careful adjustment, a vertical clutch solves the underlying problem, all but ensuring smooth engagement when starting the chronograph.

The Swiss had dabbled in vertical clutches in wristwatches as far back as the 1930s, but the technology never caught on. The Pierce cal. 130 proves the axiom that being right too early is the same as being wrong. The next chapter of the vertical clutch saga was written in Japan when Seiko debuted the cal. 6139 around May of 1969. While that movement is most famous for being (arguably) the first automatic chronograph movement, it was also the contemporary pioneer of the vertical clutch.

Mr Bürki’s coaxial design, patented in Switzerland in 1973 (Swiss patent N° 10033) and in the United States in 1975 (US patent 3879930A), keeps the driving wheel and chronograph seconds wheel on the same axis, ensuring smooth engagement. In a personal interview, Mr Bürki explained that he wanted a stutter-free start to the chronograph function, akin to how an automotive clutch engages a flywheel; the result was a crisp start with no jump of the elapsed seconds hand.

This design first surfaced in the now-legendary Lemania cal. 5100, which Omega called the cal. 1045 upon its introduction. Characterised by its central elapsed minutes counter, the cal. 5100 became popular among military aviators due to its legibility and robustness, which was due in part to Mr Bürki’s vertical clutch design. Today, most contemporary chronographs are of the vertical clutch variety, excepting those that aim to recreate the past. In this sense, Mr Bürki’s legacy lives on in movements like the Rolex cal. 4131/2 and MB&F’s Sequential chronograph, which features not one, but two vertical clutches.

Final thoughts

The story of Hugues Bürki and his school watch is a testament to Swiss horological pedagogy and the heights of institutional excellence. At the Technicum of La Chaux-de-Fonds, Mr Bürki discovered fertile ground to cultivate his talent, laying the foundation for a distinguished career. His name deserves clear recognition as an exceptional watchmaker who left a lasting mark on chronograph movement design.

The comprehensive skill set Mr Bürki mastered at the Technicum later enabled him to strike out on his own. After leaving Lemania and Omega, he set up his own firm around 1981, specialising in electrical discharge machining (EDM). Based near Neuchâtel, Mr Bürki spent the rest of his career producing high-precision parts for the numerous nearby brands.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank my wife for accompanying me on numerous trips across Switzerland, enabling me to meet with former alumni and consult local archives, and Mr. Andreas Vierhuf, a horological scholar whose decades of research and publications on school watches provided essential insight and guidance.

Back to top.