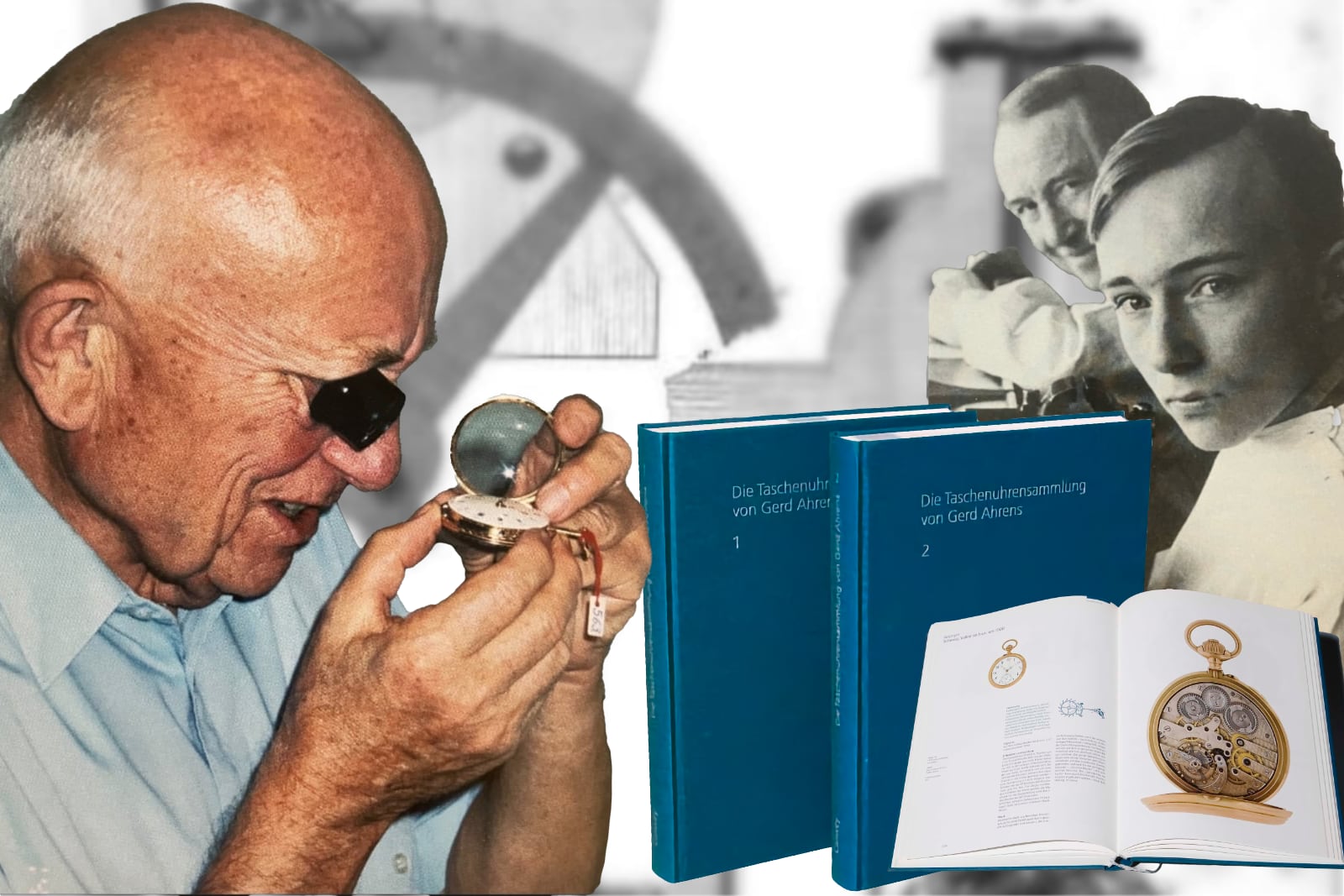

Complicated Collectors: Gerd Ahrens

The watchmaker's son who became horology's scholar-collector.

In the autumn of 1948, at Galerie Fischer’s auction house in Lucerne, a young Swiss watchmaker secured Lot 155, a Breguet pocket watch, No. 4763, circa 1848, with a straight-line club-tooth lever escapement. The case, fitted later by E. Brown at George Daniels’s suggestion to employ original movements and parts held in stock, aligned with his purpose. For most collectors, such a purchase might not have represented a pure Breguet. But for Gerd Ahrens, it was something altogether different: the first sentence in what would become a four-century narrative of mechanical ingenuity.

Gerd Ahrens in his shop office on Schwanenplatz 7 around 1955. Image – Gerd Ahrens

Foundation: a life built on wheels and springs

Gerd Ahrens was born on September 18, 1920, in Hamburg, Germany, at a time when mechanical watches represented the pinnacle of portable precision. His father, Otto Ahrens, born in 1877, had already established himself as a highly respected watchmaker. Otto’s path, however, would be marked by the upheavals of the twentieth century. Before World War I, he had operated a successful shop in Paris and had built connections throughout the watchmaking centres of Inner Switzerland. The evidence of his skill was tangible: Otto personally built ten pocket watches, demonstrating not just commercial acumen but genuine mastery of the craft.

Then the war came. Otto was forced to close his Paris shop in 1914, and the conflict left him penniless. A trained craftsman of the highest order found himself working as a janitor and technical handyman in postwar Germany, a humbling descent that must have burned deeply. But Otto’s prewar network would prove his salvation. His contacts in Switzerland and Paris led to an offer that would change the family’s fortunes: a position as workshop chief at the renowned Gübelin watchmaking house in Lucerne.

Otto Ahrens’ shop (on the right) in St. Cloud, Paris, around 1910. Image – Gerd Ahrens

The family moved to Switzerland, and Otto threw himself into the challenge with characteristic intensity. He was responsible for renovating Gübelin’s workshop, a task he completed “to the fullest satisfaction” of his employers. His work there demonstrated both his technical prowess and his exacting standards, qualities that would profoundly shape his son.

By 1929, Otto felt ready to establish himself independently once more. He opened his own watchmaking shop on Alpenstrasse 9 in Lucerne, where nine-year-old Gerd was initiated into the world of wheels, springs, and escapements. For a boy growing up in that environment, watches were the family’s livelihood, the daily subject of conversation, and the pieces that filled the workshop with quiet ticking.

Otto Ahrens was, by all accounts, a formidable personality. Christian Pfeiffer-Belli, who would later edit the catalogue of Gerd’s collection, described him as “strict, often volatile, unrelenting in his demands on himself and his employees and apprentices.” Yet this severity was paired with genuine openness to innovation. Otto “was very open to new developments in watch technology. He improved escapements, optimised gear trains, was always searching for the best watch, which, of course no one built, only he kept trying.”

This pursuit of perfection became Gerd’s lifelong standard. The young apprentice learned not only the techniques of watchmaking but absorbed his father’s philosophy: that excellence required relentless refinement, that there was always a better solution waiting to be discovered, that understanding meant not just reading but building with one’s own hands.

Gerd Ahrens and his father at the bench, ca. 1937-1938. Image – Gerd Ahrens

In 1934, when Gerd was fourteen, Otto made a strategic business decision. He moved the shop from Alpenstrasse to Schwanenplatz, in the heart of Lucerne’s old town tourist area. The location offered better foot traffic but also placed the Ahrens establishment between two formidable competitors: Bucherer toward the train station and Gübelin (Otto’s former employer) toward the city exit. For the next three decades, father and son would work at this location, building a reputation for technical excellence in one of Switzerland’s most competitive markets.

The businessman: continuity and transition

Gerd carried out his apprenticeship in the family business, learning to disassemble and reassemble the intricate mechanisms that transformed raw materials into instruments of precision. This was practical knowledge forged at the workbench through thousands of hours. His hands learned to recognise quality by touch, his eyes to detect imperfection at a glance, and his mind to grasp the logical elegance of a well-designed escapement.

In the atelier of Schwanenplatz. Gerd Ahrens is the second from the right. Image – Gerd Ahrens

In 1955, at the age of thirty-five, Gerd Ahrens assumed control of the family business from his father, who had operated it for more than four decades. This transition came at a fascinating moment in horological history. The mechanical watch industry was approaching its zenith, with Swiss manufacturers dominating world markets, yet the seeds of disruption had already been planted. Quartz technology, still decades from commercial viability, was being researched in laboratories.

The business operated under his direction until the end of December 1966, a span of nearly four decades. Yet even as he managed the practical demands of a retail business, balancing accounts, satisfying customers, maintaining relationships with suppliers, Ahrens was pursuing a parallel passion that would ultimately define his legacy.

The collector emerges: a philosophy takes shape

That first purchase in 1948, the Breguet with its unusual escapement, was far from a random acquisition but a deliberate choice that revealed Ahrens’ emerging philosophy. Abraham-Louis Breguet, who had died in 1823, represented the apotheosis of watchmaking genius. But Ahrens had not chosen a typical Breguet. He had selected one with a pierced pin-pallet escapement, a technical curiosity that spoke to his interest in mechanical solutions.

Safe drawer with watches, ca 2005. Image – Gerd Ahrens

This choice foreshadowed what would become his collecting motto: “rare escapements in pocket watches.” In this simple phrase lay a profound approach to collecting that set Ahrens apart from his contemporaries. As he would later explain in his own words: “It is the collection of an old watchmaker who understands something of the technical side.” He was interested in “the purely technical watch,” and his philosophy revealed the craftsman’s perspective: “To appreciate a polished balance staff or a cleanly ground steel part, you must have made it yourself first, then you understand the work behind it.”

The escapement is the soul of any timepiece, the mechanism that converts the steady release of energy into the regulated ticking that marks seconds, minutes, and hours. It is the component that separates a simple spring-driven machine from a precision timekeeping instrument. Throughout horological history, watchmakers had devised dozens of escapement designs, each attempting to solve the fundamental problems of friction, accuracy, and reliability. Some designs succeeded and dominated the industry. Others represented brilliant dead-ends, technically sophisticated but commercially unviable.

Ahrens articulated his unique challenge: “The challenge for me was always to collect precisely functioning watches from times when there were actually no precise watches.” This statement captures his entire project, to document the evolution of precision through the accumulated attempts, both successful and failed, of generations of craftsmen.

Over the next fifty-six years, from 1949 until 2005 when he acquired his last watch, Ahrens pursued this vision with remarkable discipline. He treated the collection as a research project, gathering material proof to tell a clear story of ingenuity and the quest for precise time.

The research network: a scholar among collectors

Gerd Ahrens approached collecting with the rigor of an academic researcher, though he operated outside formal institutions. His multilingual abilities, he could read horological literature in multiple languages, gave him access to scholarship and commercial networks across Europe and beyond. He kept himself informed about watch news from Italy, France, England, and the United States, hoarding “piles of newspaper articles, magazines, catalogues, countless calendars.”

His personal library included rarities that would make any horological scholar envious: Breguet by David L. Salomons (1921), Feinstellung der Uhren by Giebel/Helwig (1952), Drehganguhren by Helwig (1927), and Verzahnungen by Curt Dietzschold (1885). He subscribed to the major collector magazines, publications of the Antiquarian Horological Society (AHS), the French Association (AFAHA), ANCAHA, the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors (NAWCC), Chronometrophila, and the German magazine Alte Uhren.

From the late 1970s, Ahrens began corresponding with Alte Uhren magazine, sending letters on gray, embossed stationery accompanied by black-and-white photographs. These missives demonstrated his scholarly approach: he would send photos to explain signatures, show escapement details, share technical observations. Through collecting, correspondence, and publication, he took part in the international discourse on horological history.

Ferdinand Berthoud, Paris, ca. 1780. Cylinder escapement by Ferdinand Berthoud. Escape wheel in brass; two-arm brass balance; flat, under-slung spiral; Tompion-style regulator. Image – collage

He treated the catalogues of Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Antiquorum, Ineichen, Koller, and Galerie Fischer as a syllabus, reading them for learning and for leads. Each catalogue taught him about market trends, provenance, and the migration of significant pieces through the collector ecosystem.

Ahrens regularly attended auctions at Antiquorum in Geneva and Ineichen in Zürich, and also traveled to London and Paris for important sales. These were opportunities to handle watches firsthand, meet dealers and fellow collectors, and absorb the culture of high-level collecting.

Abraham-Louis Breguet, Paris, no. 1666, ca. 1805. Cylinder escapement with ruby cylinder by Abraham-Louis Breguet. Steel escape wheel; three-arm brass balance; flat, upper hairspring; regulator index with a bimetallic curb. Image – collage

One particularly memorable trip occurred in November 1980, when he attended a Paris auction with expert Jean-Claude Sabrier, then working for auctioneer Hervé Chayette. This was the first such auction in Paris in over twenty-five years, and Ahrens, knowing Sabrier well, had “a reserved seat in the first row.” During this sale, he acquired a nickel ship’s chronometer by Paul Buhré for approximately 1,100 Swiss francs and a silver savonnette with Garnier escapement and enamel dial with colourful landscape for about 5,500 francs. He even engaged in an old-fashioned trade, exchanging an old Lepine movement for a silver pocket watch with scissors escapement.

These auction experiences reveal Ahrens as an active participant in the marketplace, knowledgeable about values, strategic in his bidding, and connected to the key figures in the trade. He bought directly and attentively, a hands-on collector who insisted on seeing, touching, and understanding every piece he considered.

The architecture of a collection

By the time Gerd Ahrens died in 2005, he had assembled more than 550 significant pocket watches. When the catalogue team examined his holdings, they reviewed over 750 watches before selecting 538 for documentation. The number itself is impressive, but what distinguished the collection was its systematic organisation. Ahrens had created a four-century timeline of escapement evolution, with each watch serving as a data point in the larger story.

Christian Huzel, Stuttgart, Germany, ca. 1800. Cylinder escapement with ruby cylinder after Abraham-Louis Breguet. Steel escape wheel with eight teeth; seven-arm brass balance; flat, upper hairspring with three and a quarter turns; simple regulator index. Image – collage

Of the 538 watches selected for the catalogue, 68 feature with verge escapements. These represent the earliest watches in the collection, dating from the very origins of mechanical timekeeping in the medieval period. These primitive but ingenious mechanisms, with their crown wheel and foliot, represented humanity’s first successful attempts to regulate mechanical motion. Ahrens owned examples that allowed scholars to trace the verge’s evolution from crude early forms to refined later iterations.

The next phase of history is represented by 75 watches with cylinder escapements: an eighteenth-century innovation that offered improved performance over the verge. Invented by Thomas Tompion and George Graham, the cylinder escapement represented a significant leap in precision and became the preferred mechanism for high-grade watches throughout the 1700s. Ahrens’ examples documented how different makers adapted and refined this design.

Pierre Frédéric Droz, l´Orient, ca. 1780. Double-wheel duplex escapement. Twin escape wheels with short, blunt teeth and slight lift on the locking wheel; three-arm brass balance; flat, upper hairspring; Tompion-type regulator but with a fixed regulator scale. Image – collage

There are also 27 watches with duplex escapements: a sophisticated but challenging design that enjoyed a period of popularity in high-grade watches during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The duplex was notoriously difficult to manufacture and adjust, requiring exceptional skill from the watchmaker. That many makers attempted it anyway spoke to the competitive pursuit of accuracy that characterised the era.

More than 10% of the catalogue comprises watches with chronometer escapements; 64 in total. These mechanisms, descended from John Harrison’s revolutionary work on marine chronometers, represented the successful solution to one of the great scientific challenges of the eighteenth century: determining longitude at sea. His chronometer collection included pieces by the greatest makers in this specialised field.

Jean-Pierre Viollier, Geneva, ca. 1840. Star-duplex escapement after Charles-Édouard Jacot. Steel escape wheel with four teeth; flat three-arm steel balance; balance rim with the characteristic screwed-on, built-up “devil’s horns”; blued, upper hairspring with Breguet overcoil; simple regulator index. The impulse finger is steel. Amplitude limiting renewed by a brass pin set vertically at the balance arm; the original limiter was a small brass block on the spring acting against two pins in the balance cock. Image – collage

Finally, there are eight watches with tourbillons or carrousels: Abraham-Louis Breguet’s revolutionary 1795 invention designed to counter the effects of gravity on watch accuracy, plus the related carrousel mechanism. The tourbillon, with its rotating escapement cage, represented the ultimate achievement of traditional watchmaking. Each example in Ahrens’ collection cost a fortune to acquire, yet he pursued them systematically because they were essential to his narrative.

The remaining watches documented specialty escapements, experimental and rare designs that showcased individual watchmakers’ ingenuity and ambition, and lever escapements, the design that eventually triumphed over all others to become the standard mechanism in virtually all mechanical watches. Invented in its modern form by Thomas Mudge in the 1750s but not widely adopted until the nineteenth century, the lever escapement combined reliability, accuracy, and manufacturability in a way that no previous design had achieved.

The notable pieces: stories within the story

While every watch in Ahrens’ collection had been selected for its contribution to his historical narrative, certain pieces stood out for their exceptional significance, technical innovation, or illustrious provenance. Every piece combined function with history, an artefact with a story to tell.

New England Watch Company, Waterbury, ca. 1900. Waterbury duplex escapement. Brass escape wheel with locking and impulse teeth arranged on two levels; two-arm nickel-silver balance with rim screws; flat, upper hairspring; simple regulator index. Image – collage

His Breguet holdings formed a collection within the collection. In addition to that first watch, No. 4763, Ahrens eventually acquired Nos. 125, 1666, 2118 and 2645, among others. Each represented different aspects of Breguet’s genius, his innovations in escapement design, his elegant approaches to complications, his unmatched aesthetic refinement. For a collector focused on technical achievement, Breguet was essential because he represented the complete synthesis of mechanical excellence and artistic vision.

One watch in particular combined technical innovation with historical drama: Abraham-Louis Breguet’s “Simple Garde Temps Médaille Excentrique” No. 3469. This chronometer had been sold to Count Tolstoye on March 9, 1815, and subsequently became one of six deck chronometers used in an Arctic rescue expedition. The watch had witnessed one of the great adventures of the age of exploration, keeping time in conditions of extreme cold and motion that would have defeated lesser mechanisms.

The Jules Jürgensen decimal time watch (Movement No. 10201′) occupied a unique position in the collection. Made in 1900 for the World Exhibition in Paris, this silver watch featured revolutionary decimal time and seconds indication, a system where the day was divided into ten hours, each hour into one hundred minutes, and each minute into one hundred seconds. The decimal time system had been officially adopted during the French Revolution but never achieved popular acceptance. By 1900, it was an antiquarian curiosity, yet Jürgensen had created this technically demanding piece as a demonstration of watchmaking virtuosity. Ahrens acquired it in 1983 from Auktion Koller in Zürich, recognising it as both a technical achievement and a fascinating historical footnote.

The contemporary commission: preserving living traditions

In 1999, Gerd Ahrens did something that revealed another dimension of his character: he commissioned a new watch. This might seem contradictory for a collector focused on historical pieces, but it demonstrated Ahrens’ understanding that watchmaking was not a dead tradition but a living craft that required support and patronage.

George Margetts, London, ca. 1797. Chronometer escapement with Earnshaw spring detent. Steel detent spring; two-arm compensation balance; white cylindrical balance spring; balance with special tangential screws for fine compensation adjustment; adjustable attachment for the outer terminal of the balance spring. Image – collage

He approached Richard Daners to create a tourbillon pocket watch using traditional methods. The movement was to be made entirely from raw materials, no modern components, no compromises with industrial production. Thomas Engel, a fellow collector, provided the balance and escape wheel from his stockpile of vintage Ulysse Nardin parts and executed the exquisite guilloche work on the dial. The finished watch was signed “Für G. Ahrens Anno 1999” (For G. Ahrens, Year 1999).

This commission represented a philosophical statement about the relationship between past and present. Ahrens understood that the historical watches in his collection had once been contemporary cutting-edge technology. They existed because patrons had commissioned them, supporting the craftsmen who pushed boundaries and maintained standards. By commissioning a new piece made to historical specifications, Ahrens was participating in that tradition, ensuring that the skills required to create such watches would not die with the masters who still possessed them.

The scholar: contributing to knowledge

Gerd Ahrens sought understanding as well as ownership, documenting his findings and sharing them widely. In 1989, he published an article titled “Frühe tragbare Ankeruhren in Deutschland” (Early Portable Anchor Watches in Germany) in Schriften der Freunde alter Uhren (Writings of the Friends of Old Clocks), Volume XVI, pages 31-42. This scholarly work examined the early development of anchor escapement watches in Germany, combining technical analysis with historical research.

The article demonstrated Ahrens’ methodology. He had likely purchased several early German anchor escapement watches for his collection, not only because they were desirable objects but because they raised questions about the development and dissemination of this technology. Who were the makers? How did the design reach Germany from England where it had been invented? How did German watchmakers adapt the design? What were the regional variations? Ahrens investigated these questions systematically, examined the watches themselves for evidence, consulted historical sources, and presented his conclusions in a rigorous scholarly format.

The article has been cited in subsequent academic literature, including scholarly works on Philipp Matthäus Hahn and his successors, demonstrating that Ahrens’ contributions to horological knowledge extended beyond his collection to include original research that advanced the field.

Ferdinand Berthoud and Jean Martin, Paris, ca. 1799. Chronometer escapement with pivoted detent after Ferdinand Berthoud. Brass escape wheel with 15 teeth; three-arm bimetallic compensation balance with three round weights and three gold timing screws on the rim; the bimetallic rim is riveted with steel pins. Flat, blued steel hairspring mounted above, with the outer terminal fixed to an adjustable stud on a separate cock. Image – collage

Throughout his collecting career, Ahrens maintained meticulous personal archives that constituted detailed documentation of his research and observations. He kept handwritten catalogue notes for each watch, recording technical specifications, condition reports, provenance information, and his own analysis. These index cards, accumulated over forty years, varied greatly in their detail and format, some brief, others extensive, reflecting his evolving methodology and deepening knowledge.

In 1977, Ahrens received a letter from Ruedi Wehrli, conservator of the Kellenberger Watch Collection in Winterthur, that proved remarkably prescient. Wehrli praised Ahrens’ “unique collecting achievement,” noting that “a achievement that only ‘specialists’ can fully appreciate, but will soon be recognised by laypeople as a historical achievement.” He continued: “I believe that a collection like yours will soon be more important than the currently ‘popular’ collections of beautiful watches.” His reasoning was prophetic: “Beautiful watches will exist in the future, but the mechanical precision watch is already a historical period whose end we are experiencing.”

This letter came just as the quartz crisis was reaching its peak. Wehrli understood that Ahrens was documenting a dying tradition, or at least one that would soon be transformed beyond recognition. The collection privileged technical ingenuity at a moment of impending obsolescence, with lasting beauty present but secondary.

Market realities and personal philosophy

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Ahrens was witnessing dramatic changes in the watch collecting market. Banks were hoarding watches like gold, speculation was driving prices to unprecedented levels, and the nature of collecting itself was transforming. His reactions to these changes reveal much about his character and values.

In 1979, he wrote: “I think I have to give up collecting or switch to beer coasters and the like, the prices are going crazy.” By March 1981, his frustration had deepened. In a letter to Helmut Mann, he observed: “The whole watch market seems to me like the wave of speculation with tulip bulbs that raged in Holland in the 17th century.”

The comparison to tulip mania is telling. Ahrens recognised that prices had decoupled from intrinsic value, driven by speculation rather than appreciation. For someone who collected based on technical merit and historical significance, this market transformation was deeply troubling. Watches were becoming investment vehicles rather than objects of study.

Courvoisier Frères, La Chaux-de-Fonds, ca. 1904. Tourbillon by Mobilis with club-tooth lever escapement; steel escape wheel; bimetallic, uncut two-arm balance with gold rim screws; flat blued steel upper hairspring; simple regulator index. Image – collage

Yet Ahrens maintained his equilibrium through a personal philosophy he had inscribed on his safe door, a quote from Christian Fürchtegott Gellert: “Enjoy happily what is given to you, gladly do without what you do not have, every station has its peace, every station has its burden.” This stoic wisdom allowed him to continue collecting according to his principles even as the market swirled around him. He could not control prices or speculation, but he could control his own response, focusing on what he could acquire, accepting what he could not, finding satisfaction in what he had achieved.

The monument: a catalogue for the ages

In the early 1990s, an idea began to take shape: a comprehensive catalogue documenting the Ahrens collection. The project was first discussed with Josef M. Stadl, a pocket watch collector with a pronounced interest in watches with rare escapements and a member of the German Society for Chronometry (DGC). Stadl understood the significance of what Ahrens had assembled and believed it deserved proper documentation.

Anonymous, France (?), ca. 1790 (case 1823). Sully escapement with “pirouette”: the balance can swing through more than a full revolution, hence the term. Double brass escape wheel; three-arm brass balance with three small steel rim screws; flat, blued upper hairspring; simple regulator index. Image – collage

An initial cost estimate was prepared, but Ahrens declined. His response was characteristic: he said “he’d rather buy more watches.” For someone still actively building his collection in his seventies, the choice between spending money on documentation and spending it on additional watches was no choice at all. The watches themselves came first.

The project lay dormant until 2005, when Ahrens’ son-in-law wrote to Christian Pfeiffer-Belli, longtime editor of the prestigious magazine “Klassik Uhren.” Mr Pfeiffer-Belli assembled an extraordinary team to undertake this massive project.

Louis Tavernier, ca. 1800. Garnier escapement. Twin steel escape wheels; three-arm steel balance; flat, upper hairspring; simple regulator index. The escapement features a thin impulse roller with a ruby. Image – collage

Josef M. Stadl returned to the project as a contributor. Wolf Brüggemann, dedicated to escapement research and documentation, brought deep technical knowledge. Norbert Enders, a long-time author for “Alte Uhren,” was tasked with writing the introductory texts that would contextualise each escapement category. Peter Frieß, then the Director of the Deutsches Museum Bonn and later President of the Tech Museum in Silicon Valley, took on the enormous task of building a database from Gerd’s handwritten index cards. Ingrid Seeger joined as a contributor.

Martin Otzenberger, Gerd’s grandson, provided biographical information and family perspective. Susanne Stadl assisted with research. Peter Frieß also served as the principal photographer, documenting each watch with meticulous attention to detail. Birgit Binner handled design. And technical line drawings that would explain each escapement type with clarity and precision were supplied by an illustrator based in the United Kingdom.

Robert, London, ca. 1840. Anchor-duplex escapement. Steel escape wheel with double locking teeth; uncut two-arm bimetallic balance with gold rim screws; flat, blued upper hairspring; simple regulator index. Image – collage

The scope of the challenge was immense. Over 750 watches needed to be examined from Ahrens’ collection. As the project progressed, Gerd’s health began to decline. The catalogue, intended as his eightieth birthday present, would not be ready in time.

The team prepared sample pages and bound them together so that Gerd could at least hold a physical representation of the work in progress. He understood that the full catalogue would be completed, but he would not see it.

Gerd Ahrens died on December 11, 2005. He was eighty-five years old. His funeral was held at the Matthäuskirche in Lucerne, just steps from the Schwanenplatz shop where he and his father had worked for thirty-two years. The catalogue project continued without him.

“Die Taschenuhrensammlung von Gerd Ahrens” (The Pocket Watch Collection of Gerd Ahrens) finally appeared in 2009, published by Callwey Verlag in Munich. The scale of the undertaking was unprecedented. Two large-format volumes housed in a substantial slipcase contained 1,184 pages printed on heavy stock. The physical dimensions and weight alone reflected the ambition of the project. Published as a limited edition of 1,000 numbered copies, it was priced at €398 (approximately US$500) a price that, according to reviewers, barely covered the marginal production costs of such an elaborate publication.

The catalogue documented 538 watches from Ahrens’s collection and treated each across one or two pages in a disciplined format that reads as a working tool. Every entry opens with a life-size photograph of the dial and a movement image reduced to 60 or 80 percent to clarify layout and finish, with supplementary details when needed for case back, signatures, or technical features. A line drawing explains the escapement in clear sequence, while the text describes movement, case, dial, and hands with the economy of a bench note.

Signatures and marks are recorded in full, Ahrens’s own handwritten remarks are quoted where they illuminate construction or history, and exact dimensions in millimetres, diameter and thickness, fix the scale. Each page closes with provenance and a compact set of references to books and auction catalogues, so the reader can move directly from plate to literature without breaking the thread.

Abraham-Louis Breguet, Paris, no. 1919, ca. 1808. Lever escapement after Robert Robin. Very light escape wheel; three-arm bimetallic compensation balance with gold and platinum rim screws; upper hairspring with Breguet overcoil; simple regulator index. Image – collage

Beyond the individual entries the catalogue frames the whole project with context and navigation. It opens with a biographical sketch of Ahrens by his grandson, Martin Otzenberger, and a foreword by Christian Pfeiffer-Belli that sets out the genesis of the work. Each chapter begins with an illustrated explanation of how the featured escapement functions, so the reader arrives at the plates with the mechanism already in mind.

James Foggo, London, ca. 1810 (case 1871). Lever escapement after Robert Robin. Brass club-tooth escape wheel in the Foggo pattern; three-arm bimetallic compensation balance with sliding weights and platinum rim screws; flat blued upper hairspring; simple regulator index; rotating ruby impulse pin, as on the early levers of Josiah Emery. Image – collage

The catalogue has since become a standard reference in horological literature, regularly cited in auction catalogue, scholarly articles, and publications about pocket watches.

The dispersal: an end and a beginning

Following Gerd Ahrens’ death in 2005, the family made the decision to sell the collection at auction. This was not an unusual choice since few families have the expertise or facilities to maintain such specialised collections, and public sale ensures that the watches can find new homes with collectors who will appreciate them.

The November 2009 sale was entrusted to Auktionen Dr. Crott, one of Germany’s leading auction houses for vintage horology. Founded in 1975 and based in Mannheim, Dr. Crott had established itself as a specialist in fine, rare, and antique timepieces.

Designated as Auction No. 103, the sale was titled “Sammlung Gerd Ahrens – Luzern. 400 Jahre Entwicklung der Uhrenhemmung” (The Ahrens Collection – Lucerne. 400 Years of Development of Watch Escapements). The catalogue was prepared by Stefan Muser of Crott Auktionen and comprised approximately 500 horological lots.

Prior to the public auction, however, an important transaction had taken place. The International Museum of Horology in La Chaux-de-Fonds, with the assistance of a patron, acquired ten particularly significant pieces from the collection, as well as Ahrens’ personal workbench, the bench he had used to study and restore his watches over decades. This acquisition ensured that a representative sample would remain accessible for public education and research.

Abraham-Louis Breguet, Paris, ca. 1845. Club-tooth lever escapement by Abraham-Louis Breguet, in a straight-line layout. Brass club-tooth escape wheel with drilled teeth for improved oil retention; two-arm bimetallic compensation balance with gold rim screws; blued upper hairspring with Breguet overcoil; simple regulator index.Image – collage

The workbench holds particular significance, a tangible link to Ahrens’s working methods. The scratches on its surface, the arrangement of its drawers, the tools it once held, all speak to the hands-on approach that characterised his collecting. He bought at first hand and worked as a trained watchmaker, opening watches, studying their mechanisms, restoring their function, and documenting their construction.

In 2016, eight years after Ahrens’ death, the family made another significant donation to the same museum: his personal archives and approximately thirty additional watches. These archives represent decades of accumulated knowledge, the handwritten index cards, the correspondence, the research materials, the notes and observations that had guided his collecting decisions. For researchers studying both the history of watchmaking and the history of collecting itself, these papers are invaluable.

The auction itself was a success by any measure. Individual watches commanded significant prices, their Ahrens provenance adding to their desirability. The Abraham-Louis Breguet chronometer No. 3469, with its connection to Count Tolstoye and Arctic exploration, sold for more than €160,000. The Jules Jürgensen decimal time watch later appeared at Christie’s in 2019, where it realised CHF30,000.

Vacheron Constantin, Geneva, ca. 1845. Club-tooth lever escapement, right-angle layout. Steel club-tooth escape wheel; three-arm brass balance; flat blued steel upper hairspring; regulator index with a metal “compensation curb”; single roller on the balance staff. Image – collage

In the years since that November day in Frankfurt, watches from the Ahrens collection have continued to circulate through the market, appearing at major auction houses and in the inventories of specialised dealers. Each one carries the Ahrens provenance as a mark of quality, an assurance that the watch was selected by someone with profound knowledge and refined taste.

The legacy: what endures

Gerd Ahrens died nearly twenty years ago, yet his influence on watch collecting remains profound. This influence operates on multiple levels, philosophical, scholarly, and practical.

Anonymous, Switzerland, ca. 1870. Lever-chronometer escapement after Robert Robin. Robin “perfectionné” lever; steel escape wheel; two-arm bimetallic compensation balance with gold rim screws; blued upper hairspring with Breguet overcoil; simple regulator index. Small lifting faces on the lever pallets, so the lever—beyond its usual locking and holding role in the standard Robin design—also imparts the impulse. Image – collage

Philosophically, Ahrens demonstrated that collecting could be an intellectual pursuit rather than an exercise in acquisition or status display. His organising principle, documenting the evolution of escapement mechanisms, provided a coherent narrative framework.

His approach showed that it was possible to build a world-class collection through knowledge and discipline rather than unlimited wealth. While Ahrens certainly acquired expensive watches, his selections were always justified by their contribution to his narrative. A rare experimental escapement by an obscure maker might take precedence over a more famous piece if it filled a gap in the story he was telling.

New York Standard Watch Co., New York, ca. 1888. Worm-gear lever escapement after Robert J. Clay’s patent, with the escape wheel set perpendicular to the balance staff; worm gearing drives the escape wheel. Brass escape wheel; uncut two-arm bimetallic balance with brass rim screws; flat upper hairspring; simple regulator index. One-piece steel lever with steel pallet faces (unjeweled). Image – collage

Gerd Ahrens is consistently mentioned alongside other great twentieth-century collectors such as Hans von Bertele, Cecil Clutton, and Courtenay Ilbert. That era has passed. Rising prices, institutional collecting, and the simple fact that historical watches are finite resources make it unlikely that anyone will assemble another collection quite like Ahrens’.

The watches are too dispersed, too expensive, too sought after by museums and corporate collections. In this sense, Ahrens’ collection may represent something irreproducible, a comprehensive documentation of four centuries of escapement evolution that could only have been assembled by someone with his particular combination of knowledge, access, resources, and timing.

International Watch Co. (IWC), Schaffhausen, ca. 1894. Club-tooth lever escapement with constant-force (per Xavier Theurillat’s patent); conversion executed by Richard Daners. Twin steel escape wheels; two-arm compensation balance with gold rim screws; flat blued steel upper hairspring with Breguet overcoil; simple regulator index. Image – collage

Born into watchmaking, trained in its techniques, and steeped in its culture, Ahrens carried an insider’s understanding that moved from surface to principle. His collection reflected his personality, systematic, disciplined, focused, and profoundly knowledgeable. There was nothing haphazard about his acquisitions; each watch was selected because it reinforced the overall theme of “rare escapements in pocket watches”.

Yet he was more than a scholar in his study. The contemporary commission from Richard Daners showed his engagement with living traditions. His published research demonstrated his willingness to share knowledge. His meticulous archives revealed his commitment to documentation. His donations to the International Museum of Horology ensured that his knowledge would outlive him.

Richard Daners, Luzern, 1987. Flying tourbillon with chronometer escapement; short detent after Richard Lange; rotation period five minutes. Two-arm bimetallic compensation balance with gold and platinum rim screws; flat blued steel upper hairspring with Breguet overcoil; simple regulator index. The seconds pinion runs on the fixed, internally toothed ring wheel; the rear three-quarter plate is skeletonised. Image – collage

Setting an example

In an age when collecting increasingly focuses on investment returns, brand prestige, and social display, Gerd Ahrens’ example offers an alternative vision. He reminds us that collecting can be an intellectual pursuit, a form of scholarship practiced outside academic institutions, a contribution to preserving and understanding human achievement. His collection was not about him, it was about the watches, the makers, the evolution of technology, the accumulated wisdom of four centuries of craftsmen solving problems.

As Christie’s auction house summarised, the collection of Gerd Ahrens “was one of the most significant private collections ever assembled, impressively documenting the technical history of the pocket watch.” This assessment captures both the magnitude of his achievement and the nature of his contribution.

Ahrens’ watches have been dispersed, sold to collectors and museums around the world. But the knowledge remains, preserved in that monumental catalogue, in the archives at La Chaux-de-Fonds, in the memories of those who knew him, and in the example he set for what collecting can be at its highest level. In the end, that may be the truest measure of legacy — not what one owns, but what one contributes, preserves, and passes forward.

Amendment November 28, 2025: Images by David Penney removed from article as they were used without prior permission.

Back to top.