In-Depth: The Technical Evolution of Patek Philippe

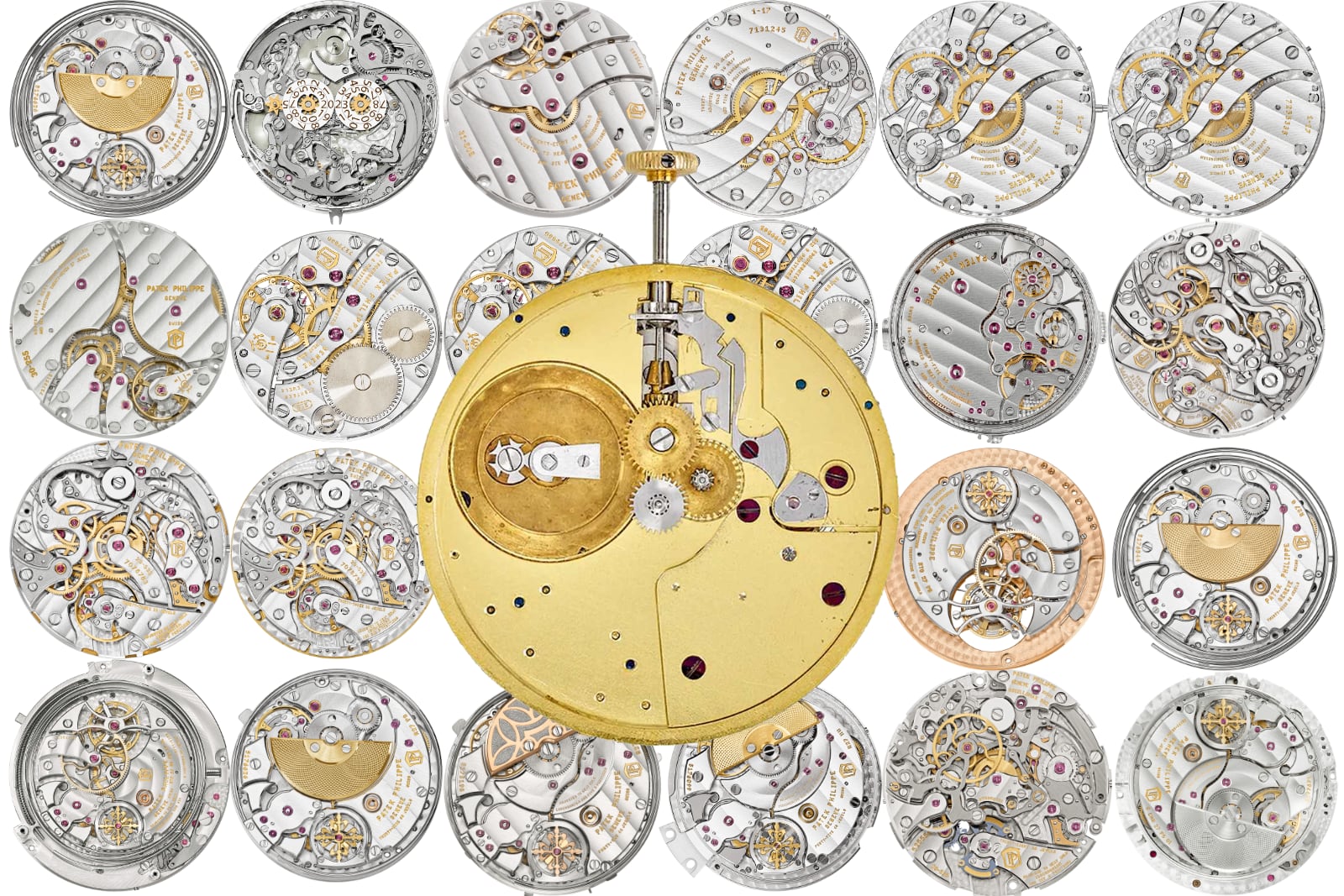

From keyless works to Advanced Research: 1839–2025.

The Patek Philippe approach to watchmaking has developed through a steady accumulation of choices. Since 1839, the manufacture has refined its mechanical language through proportion, regulation, and clarity in construction. Each calibre reflects priorities shaped by experience, built for durability, and adjusted for lasting performance.

Understanding the technical evolution of Patek Philippe requires attention to the principles that govern its construction: structural integrity, material stability, and a consistent focus on functional accuracy. Many manufacturers embraced modernity through visible transformation and stylistic experimentation, while Patek Philippe evolved through careful integration of innovation that served enduring mechanical aims. Its development follows a logic defined by proportion, restraint, and the pursuit of lasting technical harmony.

The modern-day, expansive manufacture in Plan-les-Ouates in Geneva

From Jean Adrien Philippe’s keyless winding system of the 1840s to the introduction of silicon components in the twenty-first century, progress has remained guided by internal reasoning and accumulated skill. Each movement expresses a study of mechanical relationships refined over time, where advances emerge from clarity of purpose and precision in design.

The chapters that follow trace this progression through its historical sequence. Each period reflects a technical response to changing demands: the shift from pocket to wrist, the rise of automatic mechanisms, the search for precision, and the selective use of new materials. Together, these developments form a mechanical lineage shaped by adaptation, balance, and a coherent understanding of the art of watchmaking.

The Foundation Years: 1839–1900

The origins of Patek Philippe followed no predetermined plan. They arose from a convergence of necessity, invention, and persistence. When Antoine Norbert de Patek, a Polish émigré displaced by political upheaval, founded Patek, Czapek & Cie in Geneva in 1839, the ambition to produce refined timepieces was already present, though the long-term direction was still taking shape. His early collaboration with François Czapek yielded finely made watches, and the firm’s technical path gained definition after Patek’s encounter with Jean Adrien Philippe at the 1844 Exposition des produits de l’industrie Française in Paris.

The founding agreement of Patek, Czapek & Cie in 1839. Image – Patek Philippe

Philippe, an accomplished independent watchmaker, presented a mechanism that addressed one of the most enduring functional challenges of nineteenth-century horology: the dependence on an external key for winding and setting. His crown-based system unified both functions, creating a self-contained mechanism that improved resistance to dust, simplified operation, and strengthened overall construction.

The invention earned him a bronze medal in Paris and led to his subsequent partnership with Patek. By 1851, the firm had been renamed Patek, Philippe & Cie, establishing the structure that would guide the next generation of technical development.

Adrien Philippe’s key-less winding patent. Image – Patek Philippe

The company entered the international stage later that year at the Great Exhibition in London, where Patek, Philippe & Cie received a gold medal for watches of exceptional quality and innovation. Among the exhibits was a pendant watch purchased by Queen Victoria, whose patronage enhanced the firm’s visibility and linked its name to technical ingenuity and cultural refinement. Within the workshop, the focus remained on practical progress, centred on functional clarity and durable construction.

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, Patek Philippe’s movements evolved within the Genevan tradition of mechanical legibility and structural order. Finger bridges became a defining feature, valued for the clarity they brought to the layout and the ease they provided in regulation and maintenance. Movement architecture emphasised accessible construction, visual rhythm, and stable performance across time.

Half-Hunter Gold Pocket Watch No. 17469 Patek Philippe & C° Genève, ca 1860. Image – Private Archive

Finishing was applied with regard to construction, function, and occasion. Some surfaces received decorative treatment such as polished steelwork or lightly bevelled edges, while others were executed with purely functional intent. Decorative patterns including Geneva stripes and perlage appeared in selected pieces, guided by client preference and watch type. Through this approach, the manufacture developed a practice in which mechanical integrity and visual refinement advanced in parallel, laying the foundation for the formalised decorative standards of the twentieth century.

Patek Philippe 19”’ minute repeater No. 47798, ca 1878, stem-winder lever, compensated balance, 42 jewels. Image – Christies

The firm continued to produce complications including perpetual calendars and minute repeaters while refining the fundamentals of timekeeping. Efforts centred on rate stability, endurance, and coherent construction. The introduction of the keyless works initiated a sequence of cumulative refinements. Each advance appeared modest on its own, yet together they shaped a mechanical language that influenced the company’s progress through the century ahead.

Alongside its pursuit of chronometric precision, Patek Philippe explored advanced regulating devices. In 1863, less than twenty-five years after its founding, the manufacture produced its first tourbillon movement. The mechanism, originally conceived by Breguet in 1801, illustrated Patek Philippe’s commitment to precision. These tourbillon pieces were created for observatory trials and the study of rate performance, expressing a scientific approach to accuracy grounded in experiment and measurement.

No. 27368 Key-winding lady’s wristwatch manufactured in 1868. Image – Patek Philippe

In 1868, Patek Philippe produced a wrist-worn watch for Countess Koscowicz of Hungary. Often regarded as the first Swiss example of its type, it was conceived as a piece of jewellery and also revealed new possibilities for portable timekeeping that would mature decades later. During this period the manufacture concentrated on regulating systems, case formats, and refined movement construction. Each watch combined technical discipline with cultural intent, aligning mechanical purpose and aesthetic balance.

By the closing years of the nineteenth century, Patek Philippe had established a mechanical vocabulary defined by structural logic, proportion, and respect for the regulating organ. The principles developed in this era, including sound architecture, adaptability, and endurance, formed a framework through which the firm advanced into the twentieth century.

Transition to Wristwatches: 1900–1932

At the turn of the twentieth century, the conventions of personal timekeeping began to evolve. Pocket watches, once the standard of precision and elegance, gradually yielded place to wrist-worn formats. The transformation unfolded over time, shaped by cultural habits and changing needs. Many traditionalists regarded the wristwatch as a decorative accessory associated with feminine fashion, yet the realities of modern life would soon expand its purpose.

During the First World War, the instrument proved indispensable under conditions of urgency and restricted movement. Soldiers required a timepiece that could be consulted swiftly, even when one hand remained engaged. The wristwatch fulfilled that role and, through its practicality, redirected the course of horological development.

No. 46139 presented by Adrien Philippe to his daughter Louise. Made in ca 1875, adapted to wristwatch ca. 1920. Image – Sothebys

For Patek Philippe, this evolution created a structural challenge. The firm’s reputation rested on refined pocket chronometers designed for stable positions and protected environments. The new wrist format, exposed to constant motion, temperature variation, and shock, demanded a distinct conception of mechanics. Miniaturisation alone offered no complete solution, as the conditions of use had transformed, requiring a fresh understanding of proportion, resilience, and efficiency in construction.

The manufacture advanced with deliberation. During the opening decades of the century, it continued to employ high-grade ébauches, particularly from LeCoultre, which were then subjected to the company’s own standards of finishing, inspection, and regulation. This collaborative model enabled flexibility in case design and dial configuration, while ensuring full control over the decisive stages of assembly and adjustment. The approach fostered experimentation and supported the gradual establishment of a consistent technical identity within the new format.

During these years, the firm’s design vocabulary expanded. Round cases remained dominant, yet cushion, tonneau, square, and rectangular shapes appeared with increasing regularity. Each new geometry introduced specific mechanical considerations. Movement layouts were recalibrated, and bridge structures adjusted to preserve order and balance within these new proportions. The goal remained structural harmony across every variation.

Early wristwatch calibres continued to reflect the lineage of pocket-watch construction. Finger bridges defined the architecture, gear trains followed a lateral arrangement, and subsidiary seconds at six o’clock remained characteristic. Manual winding persisted, and regulation relied on established systems such as the swan-neck regulator and the bi-metallic balance. Within this familiar framework, mechanical refinement advanced through increased jewel counts, more delicate pivots, and closer tolerances. Improvements in bridge design and compact construction enhanced stability and protection against disturbance.

In 1923 Patek Philippe sells the first split-seconds chronograph wristwatch, no. 124.824. Image – Patek Philippe

During this transitional period, Patek Philippe applied its expertise in complications to the emerging wrist format. In 1923, the manufacture completed what is now recognised as the world’s first split-seconds chronograph wristwatch (movement no. 124.824). Two years later came the first perpetual calendar wristwatch, no. 97.975, derived from a pocket-watch ébauche yet fully adapted to the wrist.

Produced in extremely limited numbers, these experimental pieces demonstrated the firm’s capacity to translate complex mechanisms into smaller dimensions while maintaining technical ambition. They also established a developmental pattern in which experience gained through pocket-watch construction guided new wristwatch architectures.

In 1925 Patek Philippe created its first wristwatch with a perpetual calendar, no. 97.975. Image – Patek Philippe

By 1932, when the Stern family assumed ownership, the transformation had reached maturity. The firm preserved its standards through careful adaptation and continued refinement. The next phase would be more decisive: the creation of a wristwatch movement conceived entirely for its format. This new foundation would support the Calatrava and signal the beginning of a period defined by deliberate engineering and cohesive design across the company’s mechanical production.

The Birth of the Calatrava and In-House Movement Development: 1932–1950

In 1932, during a period of global economic instability, Patek Philippe entered a new phase under the ownership of the Stern family. Already suppliers of dials to the firm, the Sterns brought both financial stability and a clear technical vision. They understood that the future of the company would depend on producing watches that combined formal restraint with full mechanical independence. Their first major initiative was the introduction of the Calatrava ref. 96.

Patek Philippe ref. 96, case no. 295963, ca 1939. Image – Phillips

The ref. 96 was visually restrained. Its round case and minimalist dial echoed the Bauhaus emphasis on functional clarity, proportion, and visual order. Yet its significance extended beyond design. The watch signalled a shift in the company’s approach, marking a transition from adapted forms to purpose-built wristwatches. It conveyed intent through what was included, proportional harmony, balanced typography, and controlled simplicity, and through what was deliberately excluded, such as superfluous decoration or display complications. The result was a modern wristwatch distilled to its core elements.

Patek Philippe ref. 96 with cal. 12-120PS, n°828837, ca 1939. Image – Antiquorum

At launch, the ref. 96 was powered by a 12-ligne movement supplied by LeCoultre, a common arrangement among leading brands at the time. The Sterns, however, regarded technical authorship as essential. They appointed Jean Pfister as technical director, and by 1934, the firm introduced the cal. 12-120, the first fully in-house wristwatch movement developed by Patek Philippe.

The cal. 12-120 was conceived specifically for wristwatch applications. Measuring approximately 27 mm in diameter, it followed the principles of traditional Genevan architecture: finger bridges, a subsidiary seconds display at six o’clock, and a lateral gear train. Beyond its layout, the movement was engineered to accommodate advanced finishing techniques. Its bridges featured extended bevelled edges, including sharp inward angles that required hand-executed anglage. The balance cock included a wide, circular hub polished to a mirror finish and anchored with two polished screws. Every detail was constructed to invite close inspection and to withstand it.

Detail of the manually wound cal. 12-120 PS with 18 jewels. Image – Phillips

Mechanically, the cal. 12-120 was adjusted using a swan-neck regulator and equipped with a balance wheel featuring inertia screws. Its components were designed for accessibility, with each bridge removable and each jewel serviceable. While shock protection remained minimal by modern standards, the structure prioritised stability, adjustability, and long-term maintenance. The calibre functioned as a practical wristwatch movement, developed with the same logic and discretion that had defined the firm’s pocket chronometers.

The anti-magnetic version of cal. 12-400, the 27AM240 in a ref. 3417. Image – Christies

In 1949, the cal. 12-400 succeeded the cal. 12-120. It retained the essential architecture of its predecessor but included key refinements. These included a revised regulator, improved shock suspension, and, eventually, antimagnetic properties when deployed in the ref. 3417. This model, introduced in the following decade, became the firm’s first serially produced anti-magnetic wristwatch, anticipating a growing concern among manufacturers regarding the effects of magnetism on regulating performance.

Beyond the development of new base calibres, this period also marked the formal integration of calendar complications into serial production. In 1941, Patek Philippe introduced both the ref. 1526, the first wristwatch perpetual calendar produced in series, and the ref. 1518, the first perpetual calendar chronograph manufactured in regular production. These references established new standards for how calendar mechanisms could be incorporated into the structural logic of wristwatch design. At the same time, the firm conducted experimental work in the domain of precision. A 30 mm tourbillon movement was constructed in 1945, configured for chronometric testing rather than commercial production, reflecting a continuing interest in regulating performance.

Cal. 12-120QP introduced with ref. 1526. Image – Christies

Among the most technically revealing challenges of the period was the move from subsidiary to central seconds. The display modification appeared simple but required significant reconfiguration of the gear train. In 1939, Patek Philippe introduced the cal. 12-120 SC, developed in collaboration with Victorin Piguet. This movement employed an indirect seconds drive mounted above the going train, using an additional set of wheels powered off the fourth wheel. To address the instability often associated with indirect gearing, especially the flutter caused by backlash, a tension spring was added to maintain consistent engagement.

A decade later, the firm introduced a more integrated solution. The cal. 27 SC, launched in 1949, repositioned the fourth wheel to the centre of the movement, enabling a direct central seconds indication without the need for auxiliary gearing. The design maintained the clean internal architecture of earlier models while solving a long-standing mechanical problem in an unobtrusive manner.

Cal. 27 SC here in a white gold ref. 570. Image – Antiquorum

In 1948, the firm created a dedicated electronic timekeeping division to explore emerging technologies in measurement and regulation, including early quartz and electronic escapement studies. That same year marked the beginning of its ascendancy in the Geneva Observatory trials, where its movements began to displace Omega’s long-held dominance. This trend would continue into the 1950s and serve as external validation of the firm’s technical command during a period of rapid transition in the industry.

By 1950, Patek Philippe had established a distinct technical standard for what a wristwatch movement could achieve. The calibres developed during this period combined logical layout, formal restraint, and high-precision finishing, forming a foundation that would support the company’s technical vocabulary for decades to come. These movements were engineered with clarity of purpose and constructed with the expectation that they would remain relevant far beyond their time of production.

The Automatic Era Begins: 1950s–1970s

By the early 1950s, self-winding wristwatches had evolved from novelty to established standard. Automatic calibres, once viewed with caution for their greater height and mechanical intricacy, gained wider acceptance among watchmakers and collectors. At Patek Philippe, the integration of this technology advanced through deliberate study. The firm introduced it only when the construction reached the precision, durability, and formal restraint that defined its mechanical philosophy. When the first automatic movement appeared in 1953, it represented the consolidation of an idea matured within the manufacture’s technical reasoning, shaped by internal goals rather than external expectation.

A 1954 double signed Patek Philippe Tiffany & co Platinum ref. 2526 with self-winding cal. 12-600 AT

The cal. 12-600 AT, launched in reference 2526, embodied this approach. Measuring 12 lignes in diameter, it followed the structural logic of the company’s manual calibres while introducing a centrally mounted rotor to convert motion from the wrist into winding energy. Crafted in solid 18k gold, the rotor combined efficiency with visual harmony, its mass aiding performance and its material linking it aesthetically to the rest of the movement.

The cal. 12-600 AT also defined a new internal benchmark for automatic production. Each visible and hidden component received the same care as the firm’s manual movements. Geneva stripes, circular graining, polished chamfers, and polished screw slots formed a uniform standard. The movement incorporated a ball-bearing rotor system for smooth bidirectional winding and a gear train engineered for low energy loss.

A Patek Philippe ad showing the Gyromax Balance Wheel ca 1963. Image – collage

This period also brought the broader introduction of the Gyromax balance across the manufacture’s families of movements. Conceived in the 1940s, the Gyromax replaced traditional timing screws positioned around the rim of the balance wheel with pivoting weights integrated into its plane. The design reduced air resistance and allowed precise inertia adjustment, enhancing isochronism and rate stability. Its use reflected the firm’s pursuit of regulating systems conceived within its own structural principles and integrated seamlessly into established architecture.

Patek Philippe ref. 3445 with self-winding cal. 27-460, ca 1965. Image – Antiquorum

In 1960, the cal. 27-460 succeeded the earlier model, representing a new generation of automatic construction. At 27 mm in diameter and 4.6 mm in height, it preserved elegant proportions while introducing refinements such as a redesigned keyless works, a reinforced automatic click system, and an adaptable baseplate. The design supported direct integration of date and calendar modules, including those for perpetual calendars, through a modular framework conceived for future development while maintaining balance, accessibility, and ease of service.

Patek Philippe Master Clock with digital display Slave clock MB24RS, ca 1970. Image – Sothebys

Alongside its work on automatic calibres, Patek Philippe explored other fields of precision instrumentation. During the 1950s and 1960s, the firm created quartz-based marine chronometers under the Chronoquartz designation. These instruments, built for scientific and navigational accuracy, exemplified the company’s commitment to timekeeping excellence in every form.

In 1967, an institutional quartz clock produced by Patek Philippe was installed in the Vatican, affirming the manufacture’s role as a supplier of reference-grade devices to major institutions. These projects expanded the company’s technical scope and demonstrated a consistent dedication to chronometric performance across both mechanical and electronic domains.

Patek Philippe ref. 2451 and 2594 with cal. 10-200 and 23-300, ca 1950s. Image – Heritage Auction

Manual winding movements continued alongside the automatic line. Calibres such as the 10-200 and 23-300 remained essential to the Calatrava family, where slender cases and visual restraint prevailed. The firm sustained parallel development of both systems under the same principles of precise adjustment, material quality, and regulated performance, treating each as an expression of its mechanical discipline.

By the close of the 1970s, Patek Philippe had reached a state of maturity within the field of automatic watchmaking. Its self-winding calibres expressed coherence of design, excellent engineering, and consistent operation. These watches offered convenience through mechanical grace, combining efficiency with restraint. Their worth lay in stable performance, enduring serviceability, and technical balance achieved through thoughtful evolution.

As the decade drew to its end, a new technological current emerged. The advent of quartz timekeeping, with its electronic accuracy and accessible production, reshaped the landscape of horology. For Patek Philippe, this moment called for renewed definition. The company strengthened its dedication to mechanical precision, reaffirming the enduring relevance of craftsmanship within a changing technological age.

Surviving the Quartz Crisis: The Ultra-Thin Revolution 1970s-1990s

The arrival of quartz technology, catalysed by Seiko’s release of the Astron in 1969, introduced a disruptive force that redefined the watch industry’s trajectory. Quartz movements, liberated from the mechanical constraints of gear trains, lubrication, and thermal sensitivity, delivered accuracy at a fraction of the cost. By the mid-1970s, the impact on traditional Swiss watchmaking was severe. Dozens of manufacturers either closed, consolidated, or reoriented their production toward electronic models to remain commercially viable.

For Patek Philippe, whose internal direction remained aligned with mechanical construction, this shift presented a complex dilemma. While the firm did not ignore quartz technology entirely, it resisted redefinition by it. Rather than restructure its identity around integrated circuits and electronic modules, it concentrated on reaffirming its core technical disciplines. In place of reaction, it initiated a consolidation of mechanical values and sought refinement through re-examination of existing constraints.

Patek Philippe self-winding cal. 240 with micro-rotor from 1977. Image – Patek Philippe

The result of this reflection was the cal. 240, introduced in 1977. Developed as an ultra-thin automatic movement, it departed from the centrally mounted rotor configuration used in the earlier cal. 12-600 AT and 27-460. Instead, it employed a decentralised winding system, using a micro-rotor recessed into the mainplate. This permitted a movement height of just 2.4 mm, without sacrificing functionality, serviceability, or finishing. The micro-rotor itself was produced in 22-carat gold to increase inertia and improve winding efficiency despite its compact form.

The calibre 240 retained the hallmarks of Genevan construction: finger-style bridges, hand-bevelled edges, perlage beneath the dial, and mirror-polished steel components. It was regulated by a free-sprung Gyromax balance fitted with a flat hairspring optimised for precise concentric breathing within the movement’s slender architecture. Operating at 21,600 vibrations per hour, the calibre was tuned for long balance amplitude, moderate wear, and dependable rate stability. Its construction demanded expertise in both assembly and regulation, a sharp contrast to quartz systems, which removed the need for mechanical adjustment altogether.

Initially introduced in models such as refs. 3738 and 3940, the cal. 240 became a long-term foundation for complications requiring minimal thickness: perpetual calendars, moon phases, and world time displays among them. Its dimensions allowed the layering of additional modules without disrupting case proportions. While some ultra-thin movements of the period prioritised size reduction at the expense of reliability, the cal. 240 preserved structural integrity and long-term maintainability.

Patek Philippe cal. 28-255C used among others in the Nautilus ref. 3700. Image – collage

Around the same period, Patek Philippe also introduced the cal. 28-255C, derived from the Jaeger-LeCoultre 920 base, a movement widely regarded for its slim profile and technical elegance. Used in models such as the ref. 3700 Nautilus, it exemplified the era’s emphasis on thin automatic movements with refined architecture.

The 28-255C offered a high degree of finishing and performance, yet its use remained limited. Its introduction shortly before the cal. 240 suggests a parallel exploration of automatic formats. While the JLC-derived calibre reflected a shared pursuit of slimness, the micro-rotor movement represented a more deliberate internal solution, one that would become central to the firm’s mechanical identity across the decades that followed.

During this same period, Patek Philippe participated in quartz research and production, including the Beta 21 project and its own in-house electronic calibres. However, these efforts remained peripheral to the firm’s mechanical development programme. The company continued to invest in calibre construction, decoration, and skilled personnel, avoiding the broader industrial trend of tool replacement and production-line rationalisation. Rather than accept the framing of quartz as inevitable progress, it continued to regard mechanical timekeeping as a domain of long-duration relevance.

Patek Philippe Beta 21 caliber as used in a ref. 3587:1 from ca. 1975. Image – collage

This continuity was deliberate. It rested on the belief that a mechanical watch, while less accurate by statistical measure, held value through its visible construction, repairability, and dependence on skill. The cal. 240 exemplified this position. It did not counter quartz directly, nor did it compete with it on its own terms. Instead, it represented a separate category of design logic, governed by different priorities.

When the broader resurgence of mechanical watchmaking gained momentum in the 1990s, the cal. 240 remained in production. Its construction required no reinvention, and its purpose stayed constant. The industry’s renewed interest in craftsmanship, finishing, and visible regulation aligned with principles that the manufacture had preserved through the preceding decades. In that environment, the cal. 240 functioned as a living example of mechanical watchmaking at its most enduring, a movement conceived with structural logic and sustained through disciplined execution.

Modern Renaissance: 1990s–Present

As the twentieth century approached its end, the culture of watchmaking entered a period of renewal. Collectors and a growing number of technically informed enthusiasts, many of whom had grown up with quartz watches, began to re-examine the mechanical craft. Their attention focused on durability, tactile construction, and the enduring presence of a well-made instrument. Within this environment, mechanical watches regained importance as objects of lasting utility and intellectual depth. Patek Philippe, having maintained its mechanical discipline through previous decades, was well positioned to engage this renewed appreciation through a coherent technical philosophy.

During the 1990s, the manufacture expanded its internal capabilities. It strengthened vertical integration, refined production processes, and invested in calibre development. These initiatives expressed an evolution of long-established principles within a more structured industrial framework. In 1989, the firm had marked its 150th anniversary with the Calibre 89, a pocket watch featuring thirty-three complications. That project affirmed the company’s mastery of mechanical complexity, while the years that followed directed attention toward the calibres used in daily production, consolidating the balance between craft and consistency.

Patek Philippe cal. RTO 27 PS as used in ref. 3939. Image – collage

In 1993, the firm released the RTO 27 PS, a tourbillon-equipped minute repeater calibre that represented the highest level of mechanical construction within the manufacture. Its creation illustrated Patek Philippe’s ongoing commitment to craft-intensive watchmaking, sustained even as production methods became increasingly integrated.

One major development was the cal. 324, introduced in the early 2000s as the successor to the long-serving cal. 315 family. This automatic movement, powered by a centrally mounted rotor and operating at 28,800 vibrations per hour, achieved improved rate stability and enhanced resistance to shock. It preserved the architectural character of earlier calibres like chamfered bridges, Geneva striping, polished jewel sinks, and a traditional gear train, while adopting a refined, contemporary structure. The design combined technical efficiency with the established Genevan aesthetic.

Patek Philippe cal. 324 as used in the Nautilus ref. 5711. Image – Sothebys

The cal. 324 also reflected a broader movement toward adaptable calibre platforms. It accommodated date mechanisms, dual time zones, and calendar displays while maintaining proportions suited to slim cases. The cal. 240 had pursued thinness and decentralised winding, whereas cal. 324 focused on strength and modular design. This direction promoted mechanical resilience and coherence across diverse applications, favouring balanced engineering over visual novelty.

Patek Philippe 2107 ref. 5550 Advanced Research and its Oscillomax components. Image – collage

Advances in material science further expanded the manufacture’s approach. Through collaboration with Rolex and the Swiss Centre for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM), Patek Philippe introduced its own range of silicon components within the regulating organ.

Spiromax balance springs improved resistance to magnetism and temperature variation, while Pulsomax escapements enhanced energy transmission and removed the need for lubricants on critical contact surfaces. These elements were integrated selectively, with movement architecture and finishing that continued to follow traditional Genevan principles.

Patek Philippe cal. CH 29-535 PS as used in ref. 5170. Image – collage

Subsequent developments followed the same disciplined trajectory. In 2009, Patek Philippe introduced the CH 29-535 PS, the manufacture’s first fully in-house manual-winding chronograph calibre. Retaining the traditional column wheel and horizontal clutch, it incorporated six patented innovations that enhanced energy transmission, adjustability, and long-term reliability. Early reactions centred on the design of the reference 5270, successor to the much-admired ref. 5970, yet the calibre itself established a new technical benchmark.

From this foundation emerged the CHR 29-535 PS split-seconds variant, which addressed the wear and maintenance challenges of earlier Lemania-based constructions and remains among the most precise and serviceable split-seconds chronograph movements in contemporary haute horlogerie.

That same year, the firm inaugurated the Patek Philippe Seal, replacing the Geneva Seal and extending evaluation criteria to the entire watch. The standard encompassed rate performance, case and movement construction, and serviceability, setting a measurable framework for the company’s quality discipline.

Patek Philippe cal. 30-255 PS as used in ref. 6119. Image – collage

In 2021, the cal. 30-255 PS debuted in the Calatrava reference 6119. This manual-wind movement, equipped with twin barrels and a 65-hour power reserve, featured enhanced balance inertia for improved stability. Its architecture emphasised accessibility and spatial harmony, reflecting the same principles that had guided the manufacture for generations.

Large-scale projects such as the Grandmaster Chime of 2014 demonstrated mastery of acoustic and calendar mechanisms, while the simpler three-hand references continued to express the firm’s essential mechanical language, refined through balance adjustment, finishing, and positional regulation. Each tier of production illustrated a single philosophy: the pursuit of precision through measured design and enduring craft.

Conclusion: The Patek Philippe Technical Legacy

Throughout its history, Patek Philippe has treated mechanical progress as an unfolding architecture, where each generation of movements extends the reasoning of the last. The company has built a mechanical language defined by precision, proportion, and disciplined evolution. Each advance extends established principles through deliberate refinement, with progress expressed through practice and construction more than through proclamation.

From the creation of the keyless winding system in the 1840s to the integration of silicon components in the twenty-first century, the company’s trajectory has developed cumulatively. Each generation of movements has drawn from the structural logic of its predecessors. This approach has preserved technical integrity across changing materials, formats, and expectations, allowing the manufacture to evolve while remaining grounded in its essential mechanics.

Several principles give form to this philosophy. The first is precision, understood as a comprehensive discipline that encompasses design, adjustment, manufacture, and finishing. Accuracy in rate is one expression of it. The alignment of wheels, the engagement of teeth, and the geometry of each bridge are arranged to sustain stability, reduce friction, and maintain internal order. Quiet operation, balanced amplitude, and straightforward regulation are treated as integral to performance.

A second principle concerns longevity. Movements are designed to remain serviceable across decades through regular maintenance. This expectation shapes proportion and construction: case sizes remain moderate, layouts accessible, and materials selected for reliability. New elements are introduced through measured evaluation, ensuring that every component strengthens the whole. Longevity, in this sense, arises from discipline in design and respect for mechanical balance.

Patek Philippe cal. 240 Time Line for its 40 years anniversary in 2107. Image – Patek Philippe

A third principle lies in finishing. Within Patek Philippe’s practice, finishing operates as an element of construction, integral to the watch’s function and form. Polished steelwork, bevelled edges, and decorated main plates are regarded as essential to the build, regardless of visibility. These surfaces express precision and accountability, creating a vocabulary of control that defines the manufacture’s mechanical aesthetic.

The final principle is mechanical harmony. Movements are conceived with attention to symmetry, spatial proportion, and coherence between form and function. Every element follows a consistent internal order, and variations occur only when justified by necessity. The result is a mechanism that unites technical purpose with visual equilibrium.

Together, these principles form a methodology that informs every level of production. It extends beyond individual models or complications, shaping the design and construction of each watch. Progress unfolds as an accumulated process, guided by long-term reasoning and cumulative improvement. Refinement serves as the central expression of advancement, aligning invention with the enduring logic of mechanical design.

Within an industrial landscape driven by replacement and immediacy, this method offers a different rhythm. Patek Philippe’s watches are built to endure mechanically, visually, and conceptually. Their strength lies in consistent performance, maintainable structure, and the capacity to remain intelligible to future craftsmen.

This constitutes the technical legacy of Patek Philippe: a lineage built through precision, structure, and measured evolution. Each movement stands as both a functioning instrument and a record of accumulated knowledge, an expression of watchmaking conceived as a living, advancing architecture of time.

Back to top.