Editorial: Tales & Technology – Why a Dufour Hammers for More Than a Greubel Forsey

Delving into one of the conundrums of the watch market.

Just two days ago at Phillips’ Hong Kong watch auction a pair of timepieces that are masterpieces of contemporary independent watchmaking went under the hammer with dramatically different results.

The first was a Philippe Dufour Simplicity that sold for US$258,000, about five times its original retail price some 12 years ago and just a day after Christie’s accomplished the same with another example. And then three lots later came the Greubel Forsey Invention Piece 1 (IP1), a 2009 watch that came straight from the collection of Jean-Claude Biver no less. It went for modest US$226,000, less than half of the original retail price.

In absolute terms the Simplicity didn’t go that much better than the IP1, about 10% more. But relative to the original prices the disparity is significant, and so was the interest in each watch during bidding. The Simplicity handily crossed its high estimate, while the IP1 lingered awkwardly below the low estimate, hammering just below it.

Both watches are intrinsically very, very good. With a movement decorated to an ethereal degree, the Simplicity is a well known watch over which much praise has been lavished, despite Mr Dufour having made as many as two dozen more than originally promised (starting with four more than the initial run).

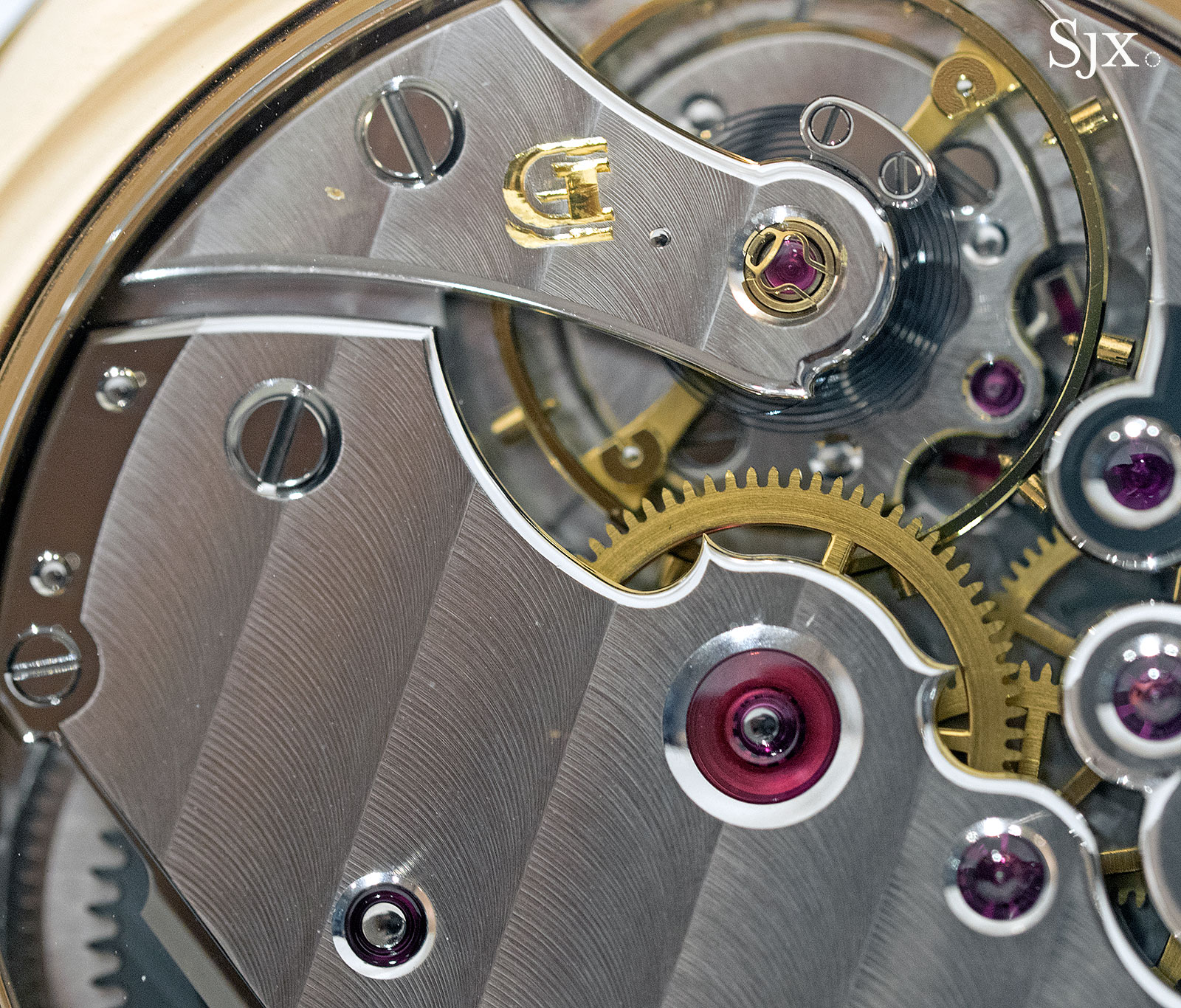

But Greubel Forsey’s work is also unquestionably excellent. The complexity of the brand’s movements is astounding, as is its remarkably fine finishing – qualities that are obvious even in casual photos.

In fact, both the firm and Mr Dufour are partners, both in horological education alliance Time Aeon as well as Le Garde Temps Naissance d’une Montre, a project dedicated to preserving the techniques to produce old fashioned, hand-made watches. Greubel Forsey and Mr Dufour are in many ways peers, artistically and philosophically.

Inside the most entry level of Greubel Forsey’s watches

So why the diverging fates at the recent sale?

There are several possibilities, the obvious ones being tangible. Greubel Forsey’s watches are mostly large, being wide and thick, making them less wearable than the modestly sized Simplicity. That being said, there are plenty of extremely large contemporary watches that sell well, from the likes of MB&F, Hublot and so on. Such large watches bank on being flashy, and Greubel Forsey watches are hard to miss on the wrist. Physical size is not sufficient as an explanation.

Or it could be just a matter of supply. Greubel Forsey has produced about 1000 watches in its 12 years in existence, a number confirmed by co-founder Stephen Forsey. That’s five times more than Philippe Dufour has made in twice as long.

Given Greubel Forsey’s price point, they average US$300,000 at retail, having 1000 in circulation looms large. But in absolute terms it is not very many. F.P. Journe produces about 800 a year, and at the other extreme, Patek Philippe between 50,000 and 60,000 annually.

If it’s not the number alone, it could be merely the general malaise in the market for modern, high-end complicated watches, a sad but unavoidable situation. The same reason is why watches like the Patek Philippe Sky Moon Tourbillon and Lange Tourbograph at the very same auction did not sell.

But there’s one more, inconspicuous explanation that relies on the subtleties of brand positioning.

Physically Mr Dufour is the archetypal watchmaker, with white hair, a pipe and a watchmaker’s coat. He looks the part.

More importantly, Mr Dufour has, whether shrewdly or unintentionally, burnished that image over the years with his carefully stewardship of his own brand. He never wavered from the standards of quality set early on, while doggedly sticking to his signature timepiece.

All the while appearing in the right places and saying the right things – he always has harsh words for lazy watchmakers who finish movements with lots of machines and little effort – enough to become the living embodiment of mid-20th century Vallee de Joux watchmaking. He is the lone warrior fighting the tide of lazy modern technology, valiantly doing things the old way, the way things should be done. That is an awfully compelling story.

Greubel Forsey, on the other hand, lacks a single individual behind it. Stephen Forsey is a vibrant public figure in watchmaking, Robert Greubel is almost invisible. The company essentially began as a two-man partnership but has since styled itself as a corporate entity – helpful for longevity but providing less appeal in the short term. Having the man, or men, whose name is on the dial of the watch actually deliver the watch is a wonderful experience.

And Greubel Forsey is selling watches equipped with cutting edge tourbillon regulators – essentially technology. Invention Piece 1 sounds like a gadget, and so do Double Balancier 35° and Tourbillon 24 Secondes. While its watches are extraordinarily well made, they are marketed primarily as highly complex pieces of miniaturised mechanics, rather than vessels carrying a lost art into the future.

That’s exacerbated by the fact that tourbillons have become commonplace, becoming the dead golden goose. Having build its reputation on creating the very best tourbillon, Greubel Forsey has painted itself into a corner.

Ironically Philippe Dufour often speaks about the benefits of technology to produce better watches – not high-tech watches but low-tech watches made better with the aid of tech. He has revealed publicly on many occasions that he learnt computer aided-design to create the movement of his grande sonnerie wristwatch. What he does rail against is the use of high-tech shortcuts in movement finishing.

In some respects Greubel Forsey has refined Dufour’s approach even further, using technology to build impressively complex and imaginative movements, while still sticking to old fashioned hand finishing of the movement components.

So the market isn’t really a conundrum, but a complicated mix of factors that throw up surprising results.

Back to top.