The Ad Man Who Made The Best Watch in The World

Alan Downing tells the story of René Bittel and Patek Philippe.

In the luxury watch industry, tradition demands that those who do the actual work of designing, making and promoting the products remain anonymous, for in the culture of luxury, the sole fount of creativeness, craftsmanship and sheer genius is the brand.

Thus in the history of the Geneva watch manufacturer Patek Philippe you won’t find any mention of René H. Bittel, the advertising man who propelled a moribund, little-known company to the height of prestige and renown as the maker of the best watches in the world.

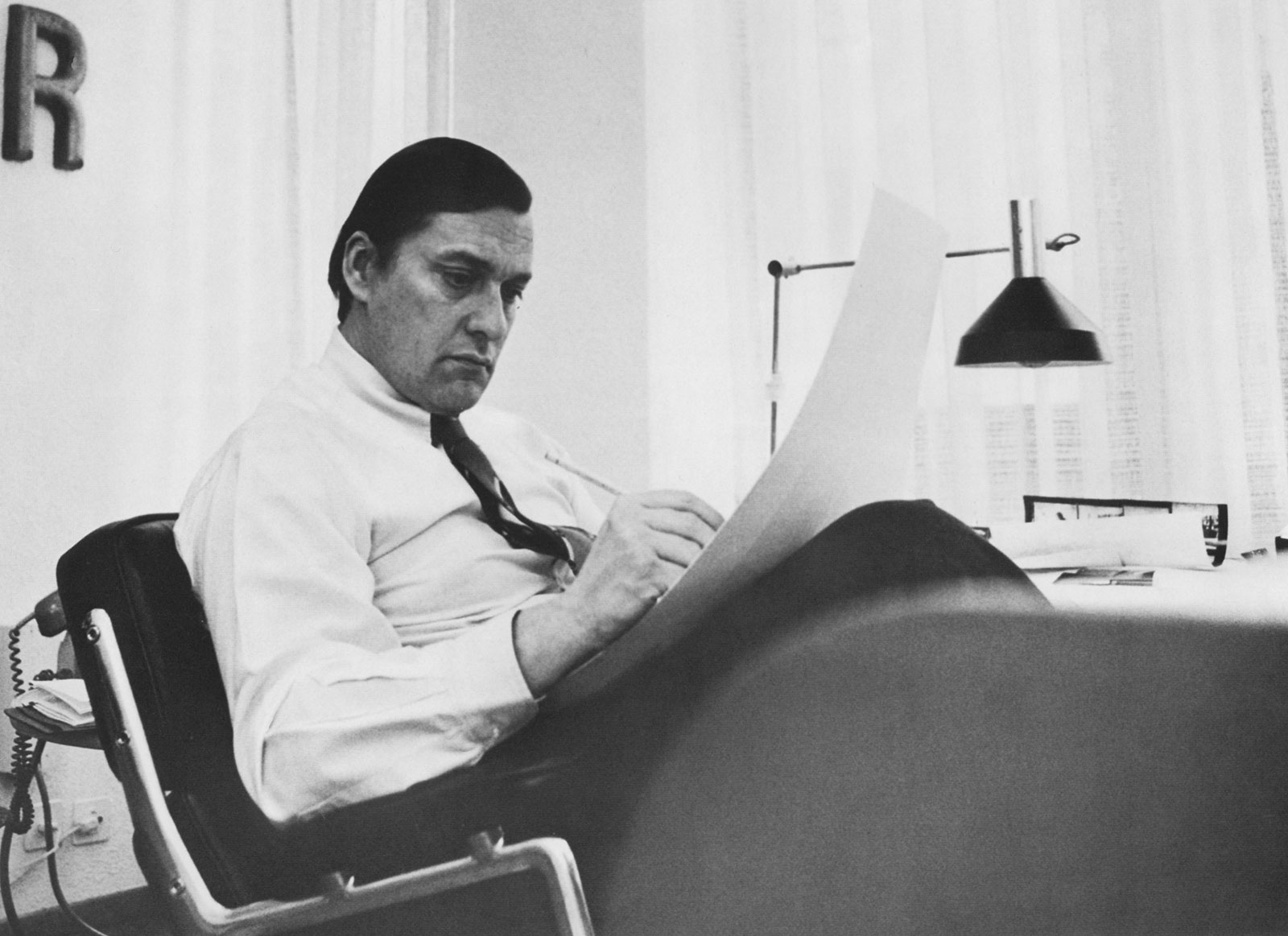

From a remote hamlet in the Swiss Alps of eastern Valais, Bittel (pictured above in the early eighties) was a product of the ruthless world of Madison Avenue in the golden days of Mad Men. He was a talented art director and extremely versatile graphic designer with a penchant for typography influenced by Herb Lubalin.

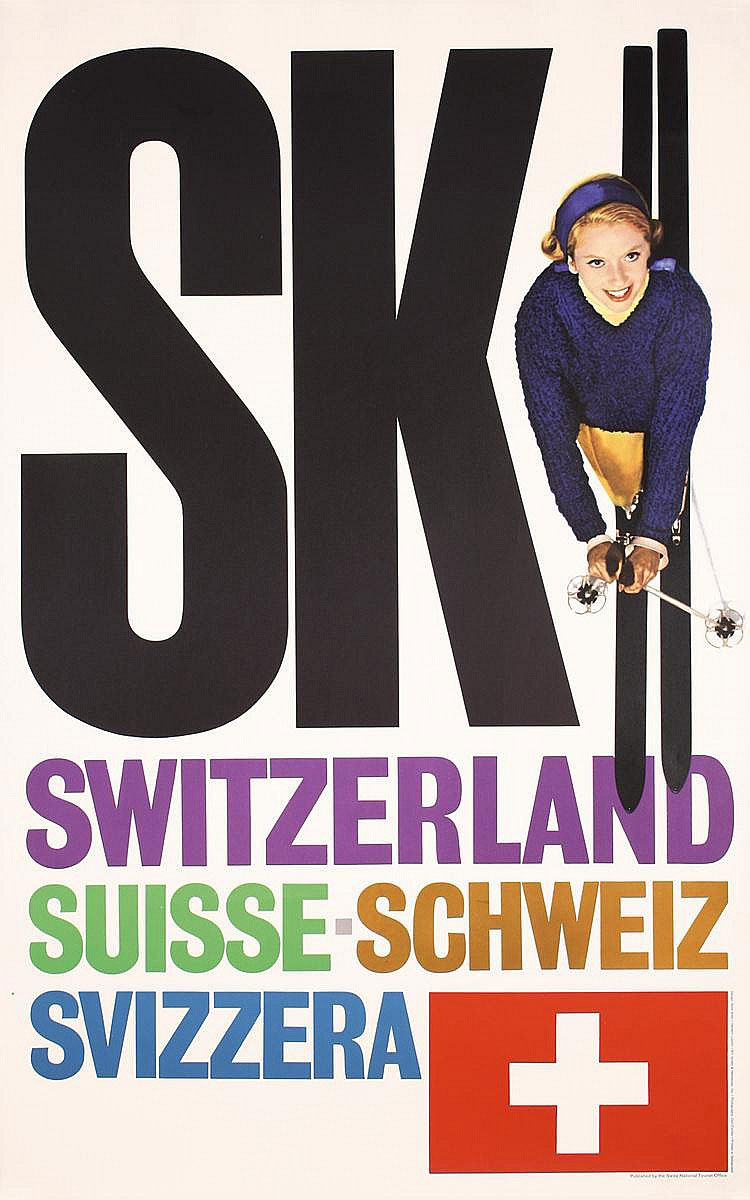

In New York, Bittel created a number of eye-catching posters for the Swiss tourist office and Swissair. Credit Herb Lubalin Study Center

Working internationally from his Geneva studio he amassed an impressive portfolio of posters, cover pages, magazines, packaging and successful advertising campaigns for a wide range of industries. In 1984, Bittel acquired the Geneva branch of an international advertising agency, Kenyon & Eckhardt, giving him the network to conduct global campaigns for local clients. Fortuitously, it was then that Patek Philippe came to him with a problem.

In late 1984, the Geneva watchmaker was at a low ebb.

Production of mechanical watches had slumped to around 5,000 a year (plus about 3,000 more quartz), well below the capacity of its riverside factory in the Jonction district of Geneva, built at the height of the watch boom in the sixties. Although a scattering of old-money families knew that a watch from Patek Philippe was the best you could own, they kept the secret to themselves, while the few who owned a Patek Philippe watch felt no need to buy another. It was a watch for a lifetime.

However a new wind was blowing through the quartz-shocked industry. Jean-Claude Biver had launched the mechanical revival with the newly resurrected Blancpain name under the slogan that it had never made a quartz watch since 1753 and never would.

The new wind brought a familiar scent to Patek Philippe’s sensitive antennae: new money. Thatcherite neo-liberal economics, privatisation and the “Big Bang” deregulation of the stock exchanges had spawned the high-spending, status-seeking yuppie.

Advertising seemed the obvious way to reach this potential market. Patek Philippe wanted Bittel to convince these bonus-rich financial speculators, who had never heard of Patek Philippe and who knew nothing but quartz watches, to spend a lot of money on an obsolete product because it was the best watch in the world.

Bittel’s first task was to give the brand an identity. Nobody knew what a Patek Philippe looked like, so Bittel designed the archetypal Patek Philippe watch. The hobnail-bezel Calatrava ref. 3919 became the face of the brand in its first global advertising campaign and subsequently its best selling model.

Bittel believed in words as much as in pictures. The words were supposed to make the reader believe that Patek made the best watches in the world without committing the vulgarity of actually saying so.

His English language copywriter, who also worked as a news journalist, recalls his agency experience:

“Pressed by a deadline, it generally took me less than 20 minutes to wrap up a news story in 100 words. But it took almost as many weeks to write the 100 words for Patek Philippe’s advertising campaign. It needed brainstorming sessions, consumer research and concept analyses. Version after version of the copy went through dozens of hands all the way to Philippe Stern and back.

Bittel, being a Madison Avenue veteran, milked the approval ritual for as long as he could. Eventually he decided to give me a lesson in copywriting. ‘Sell the sizzle, not the steak,’ he commanded. So my copy sizzled. Still they weren’t satisfied.

Then my phone rang one night. It was Bittel. He’d had a brainwave. ‘More R,’ he said.

‘R’?

‘Yeah, R. As in Rsome, you asshole. Don’t you understand English?’

After a further exchange of similar compliments, it transpired that what the copy needed was awe.

The next morning I rushed off 100 words of awestruck drivel. It took me about 20 minutes. They hit the Patek Philippe G-spot. I discovered the secret of copywriting for the luxury watch industry. Awe. The writer must be humbled by the magnificence of the brand, dazzled by the splendour of the product. It never fails.”

Bittel discovered two things about the newly rich of the 1980s: they travelled a lot and bought luxury items when they travelled. So Bittel’s modest looking monochrome advertisement followed them through the air, airports and hotels in the financial press, magazines and posters.

The campaign was greeted with outrage from the Patek Philippe loyalists, upset that their exclusive watchmaker was being bandied about among the proletariat.

Yet, within two years Patek Philippe’s sales increased 28% to reach SFr81m. The total number of watches sold (quartz included) rose 35% to 12,107 in 1987.

“This is a Patek. Have one.” Bittel’s hands offer the watch he created for Patek Philippe’s monochrome “image” campaign that ran for 10 years.

It seemed that there was nothing that Bittel couldn’t do. He designed more watches for Patek Philippe’s 150th anniversary, including the “Officer’s Watch,” produced all their catalogues, manuals, product and press releases, the book for the Calibre 89 supercomplication, 19th-century style oil portraits of the founding fathers, designed logos and display material, conducted consumer surveys and crafted more original advertising.

Although charming with clients, Bittel was a martinet at the agency. He was man of imposing bulk with a huge head, tearing off the filters of French cigarettes and chain-smoking them as he berated his staff. His graphists laboured in terrified silence. He had the girls in tears. However, the atmosphere was somewhat lightened by the outrageously camp Carlo Schmalz, his account manager.

Bittel found an intriguing way of displaying a brand’s watchmaking prowess in a mock-vintage advertisement combining old-encyclopaedia drawings and quaint text.

By the early nineties, Patek Philippe’s production couldn’t keep up with demand. Bittel produced old-fashioned long-copy advertisements explaining why you had to wait so long for your Patek Philippe and why it cost so much. Their immediate effect was that the waiting lists grew even longer and the prices soared.

Patek Philippe ended its 12-year relationship with Bittel’s agency (by then called Bozell) in 1996. Within a few months, Bittel died suddenly aged 67. He might have been a coarse bully, but in the interests of his client he was relentless and totally professional. The excellence and originality of his work showcased the quality of the brand.

Patek Philippe’s generous budget had been well spent. Bittel acquired an XK120 Jaguar, a number of expensive artworks and an Arabian stallion.

Patek Philippe’s watch production was nearing 40,000 and prices had tripled. The company went into expansion mode with its new factory at Plan-Les-Ouates. And anyone with more than a passing interest in time knew that Patek Philippe made the best watch in the world.

Back to top.