EDITORIAL: Silicon And Soul

Silicon is already the next big thing in watchmaking, having gone from experimental and exotic to being widely adopted by major brands. But is it at odds with the fundamental purpose of mechanical watchmaking, to demonstrate craft and skill?

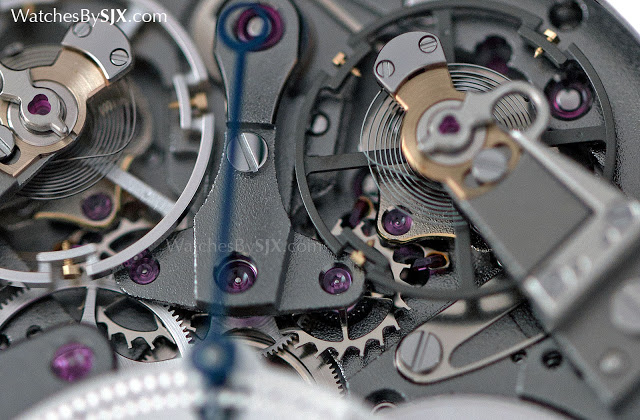

Finishing, assembly, regulation – all of these require manual labour, craftsmanship even. Historically the human touch was needed because of the imprecision of raw components. Tolerances were insufficiently fine, so hand finishing and regulation had to be done. Levers and wheels had to be ground down and refined, and the balance wheel had to be poised.

But advances in manufacturing mean such techniques have evolved, becoming decorative rather than functional. The lavishly decorated movements visible through a sapphire back don’t actually need most of the lavish decoration. A solidly reliable mechanical timepiece can be made with the bare minimum of manual labour. The $50 Seiko 5 automatic is proof of this. And the Swatch Sistem51 takes it even further. It manages to keep decent time despite being made entirely by machine with lots of glue to hold it together. But high-end watchmakers still respect tradition – or heritage, savoir-faire and patrimony as they like to put it – how much of an artisanal craft watchmaking is.

So it is ironic that many watchmakers are pursuing new materials that promise to make watches better, but less artisanal. And it’s not just mass market brands that are wholeheartedly adopting silicon, but even haute horlogerie brands like Patek Philippe and Breguet.

|

| Silicon hairsprings with Breguet overcoils in the Breguet Tradition Independent Chronographe |

The most enthusiastic take-up of silicon in movements has been at Rolex, Patek Philippe and companies of the Swatch Group. All three are shareholders of Centre Suisse d’Electronique et Microtechnique, the cantonal research and development lab in Neuchâtel better known as CSEM. Essentially all the development of silicon as a material in watchmaking has been undertaken by CSEM, which is why non-shareholders have not adopted silicon as widely. Richemont Group companies for instance barely utilises silicon in their movements. Instead, Cartier has embarked on developing alternatives, most notably artificial diamond, which it has used in its ID concept watches as well as the commercially available Astrotourbillon Carbon Crystal.

.jpg)

The most widespread use of an advanced material in watchmaking is silicon for the parts of the escapement, usually for the escape wheel, pallet fork or hairspring. Because silicon parts are made to incredibly fine tolerances, such components are perfect in every instance, literally ready to go fresh out of the oven. This makes manufacturing more efficient. Silicon’s physical properties also make it ideal for movement parts, being non-magnetic and possessing of a low coefficient of friction. And the oxidised silicon used for watch parts is also stable with varying ambient temperature. Such properties increase reliability, and reduce rates of return.

The fact that the two largest brands in Switzerland – Rolex and Omega – both use silicon hairsprings means the material makes a watchmaker’s job meaningfully easier. Proof can be found in the fact that Omega offers a four year warranty with its silicon hairspring-equipped watches, while Rolex recently extended the warranty for all its watches to five years (having introduced its own Syloxi silicon hairspring last year). That doubles the industry standard of one or two years.

Silicon lacks the romance of brass or steel. Perhaps it even looks out of place in a traditional haute horlogerie complication. More importantly, might such advances mean watchmakers are innovating their core competency away? Such technological progress is perhaps at odds with the fundamental purpose of the high-end mechanical watch – it’s art rather than technology.

Silicon parts prove that all the centuries of accumulated know-how is irrelevant because a better mechanical watch can be made, not with human hands, but machines. Does that blur the line between a quartz and mechanical watch? A quartz watch can be excused for being a better timekeeper because it is a fundamentally different technology, but is a perfect mechanical watch a dangerous thing?

That perhaps exaggerates the questions but it is a salient point. And some in the industry have been thinking about it. A senior executive at a major watchmaker believes that eventually the industry will develop new artisanal techniques for new materials, perhaps methods of decorating silicon. Silicon might make up the entirety of the escapement, but the rest of the mechanical movement remains traditional, at least for now.

Back to top.